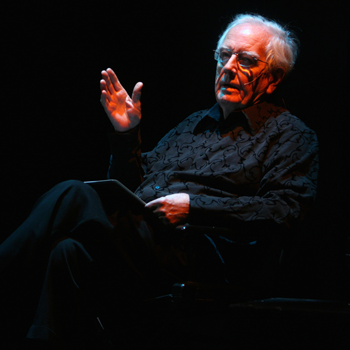

According to Robert Ashley, the composer himself, “Well, if I say

it’s opera, it’s opera! Who’s running this show, anyway?” The composer,

who died in March of last year, was known for anecdotal libretti and

“television operas” that invite close listening and that range in tone from

tragic to comic to cosmically, bewilderingly existential.

Crash , the last of his operas, was performed at Roulette by

Varispeed, an experimental music group consisting of a younger generation of

Ashley disciples: Brian McCorkle, Dave Ruder, Gelsey Bell, Paul Pinto, Aliza

Simons, and Amirtha Kidambi. First performed last year at the Whitney Biennial,

Crash was reincarnated for four nights in April by director Tom

Hamilton and producer Mimi Johnson. The opera is divided into six acts of

fifteen minutes each, during which three of the speakers, in a Cageian fashion,

take turns talking for 30 seconds each: “Thoughts” rambles, as if partaking

in a phone conversation, about fourteen-year life cycles, evil short men, and

the frustrations of neighbors; “Crash” swirls out a string of poetic fears

and musings; “The Journal” stammers out descriptions of each year from

Ashley’s life. Meanwhile, the other three voices murmur quietly in the

background. The members of Varispeed rotated through the parts so that, by the

sixth act, each had taken his or her turn assuming each of the voices and their

varying tempos and amplifications.

Roulette TV: ROBERT ASHLEY // Crash: Act 1 from Roulette Intermedium on Vimeo.

Unlike other of Ashley’s operas, which feature loosely outlined piano or

electronic parts, Crash is distinct in its accompaniment: each of the

three trains of thought, which thread in and around each other like a braid of

multicolored ribbons, is joined only by the quick but quiet mumbling of three

other voices and an array of three different photo projections. This symphony

of voices and abstract images allows the focus to fall not just on Ashley’s

texts but on the spotlighted speaker and the hills and valleys of their

inflections, vocal register and timbre, and unique embodiment of the

“character”. So although the opera is sparse in requisites, it feels

inordinately full and rich in tone as the six voices—four voices at any given

moment—complement each other in continually new ways. (The interpretations of

“The Journal” were most striking in their differences, as each of the

members of Varispeed adopted the required stutter in a particular way.)

Despite this sense of evolution in the ever-fluctuating vocal combinations,

there was an overall sensation of constancy and meditation throughout the

comforting rhythms and switch-offs of the 30-second segments. Each time one of

the characters started back up, no matter who was speaking, the carefully

intricate yet seemingly stream-of-conscious themes and anecdotes of Ashley’s

life fell into their familiar patterns. The mathematically predictable

structure of the opera was the perfect framework for Ashley’s unpredictable

and often humorous observations. Each of the vocalists managed to capture the

ponderous, philosophical, and psychological ramblings—which in the case of

“The Journal” were highly linear and easy to follow, while during

“Crash” they were more obscure—with not just humor but sensitivity and

musicality.

Another reason, aside from the scrupulous performance of Varispeed, that

Ashley’s personal accounts and musings never felt heavy-handed or forced were

the photographs by Philip Makanna, who collaborated with Ashley on the

latter’s 14-hour video opera/documentary Music with Roots in the

Aether. Throughout the “projection score” by Katie Cox, Eric Magnus,

and Andie Springer, the abstract and peaceful visual component did not feel

like a contrived, maladroit powerpoint sequence as so many new music

projections do. Rather, the photographed landscapes not only depicted the

American scenery so important to Ashley, but also allowed the audience to

“hear the singing and the texts without the typical visual distractions”,

as Ashley desired. In combination with lighting designer David Moodey’s

skillful spotlight maneuvering and Kate Brehm’s stage management, the photo

projections did not hammer home a message but allowed the viewers to form their

own responses alongside their listening. This was the rare opera experience

wherein the visual and aural experiences were united with not a blip of

disjunction.

More straightforward than Ashley’s other operas, which can be oblique and

convoluted in narrative and musical structure, Crash delivers a

wondrous yet meditative experience. Written at the end of the sixth

fourteen-year cycle of his life—and it’s surely no coincidence Ashley died

just before his 84th birthday, considering his self-imposed

significance on the number—the opera feels as if Ashley is looking back on

his life while also looking towards the future, using the voices of young

people to explore concepts of voice, story-telling, and, yes, opera.

Rebecca S. Lentjes