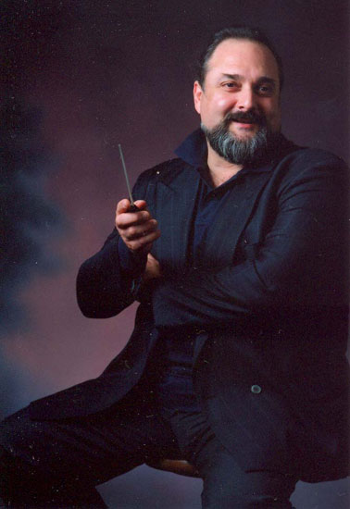

A big

man, oozing Italian warmth, he has been conducting in Japan for fourteen years,

teaching in leading Japanese music schools, as well as finding time for master

classes back in the Conservatorio Santa Cecilia, Rome, where he was a student

in the past. He sees himself as a cultural ambassador, not just promoting

Italian opera in Japan, but opening Japanese performers and audiences to a

particularly Italian way of doing Italian opera.

He explains that he grew up “inside of the opera,” and has loved the

medium as long as he can remember. Both his parents were opera singers. His

father, the baritone Giulio Mastrangelo, travelled the world in the course of

his operatic engagements; Stefano was conceived in England and has the middle

name “Sydney” for his father was singing in Sydney, Australia, at the time

of his birth in 1955. Many of his parents’ friends were opera people. He

learned the French horn from an early age, and entered the Scala orchestra in

1977. He was drawn into conducting by Giuseppe Sinopoli, whose assistant he was

for fifteen years. He remembers Sinopoli as “a very, very difficult

person,” but also a huge inspiration; in his own conducting he considers

himself “strongly influenced” by the older conductor and “continuing

Sinopoli’s work in Japan.” Indeed he remembers Sinopoli saying that “the

future of opera lay in Asia, and especially Japan.” Mastrangelo understands

this to mean that not only was there a huge audience for European classical

music in Japan, but a great willingness to cherish and nurture performance

traditions.

Mastrangelo does indeed see the future of opera in Japan as a lot more

promising than anything Europe has to offer. “Opera in Europe is finished,”

he exclaims warmly at one point, before dilating at length on the problems

facing the Teatro dell’Opera in Rome - problems that he feels are part of a

wider cultural crisis. He is unsparing in his diagnosis of where opera in

Europe has gone wrong. There has been far too much state subsidy, creating an

unreal production atmosphere in which the audience was not considered to matter

very much. The major European companies have bloated administrations, employing

dozens of staff who may have little or nothing to do with music. And far too

many productions have relied on striking, often shocking, visuals that have

seldom done much to bring out the “emotional core” of the operas onto which

they were expensively hitched. Mastrangelo contrasts all this nostalgically

with the “simplicity” of the old impresario system that reigned in

Verdi’s day. He feels that Japan has, so far, avoided most of the European

mistakes.

He speaks very affectionately of the Japanese: “they have a lot of passion

for opera; they want to make it their own.” At the centre of Japanese

operatic life, he sees a hard core of wealthy opera lovers: people who will

travel the world to see the operas they want to see, and who will invest time

and money in operatic production in Japan. It was such people, he explains,

whom he encountered in Italy, and who persuaded him to come to Japan in the

first place. They were aware of the danger of insular standards, and wanted

Mastrangelo to propagate “traditional Italian” values. To do this, he has

set up what he has christened the Mirai Project, or “Future Project,” to

educate singers, musicians and directors in Italian ways of doing things. The

goal, he says, is to reach La Scala levels, and La Scala conveniently provides

a symbol of steady progression: it is a matter of gradually ascending steps, or

stairs, until Japanese performers are at the top. He sees no point in aiming at

anything less.

Mastrangelo deplores the fact that German ideas about classical European

music have had such a profound influence in Japan, so that Bach is considered

the quintessential European genius in music in the same way Shakespeare is in

literature. He feels this has led to an excessive emphasis on correctness as

opposed to expressiveness; often what he calls “the heart” of the music is

not brought out, or felt. He considers “creating emotion” to be central to

the Italian musical ethos, and this lies at the heart of the Mirai Project.

Music schools, he says, should teach literary appreciation as a matter of

course. Singers need to understand exactly what they are singing, and be able

to bring out not just the beauty of the words, but their particular dramatic

inflection.

Getting back to Europe, I put it to Mastrangelo that though European

productions may often rely too much on shock tactics, they do at least stir

debate; while all the Japanese productions I have seen have presented operas as

completely inoffensive classics to be savoured, above all, for their musical

beauty. Should opera shock, at least a little bit? He pauses before replying,

and when he talks about how opera has been shocking people for 400 years, I

feel he is still trying to arrange a diplomatic answer. Finally he gets to the

point: any opera should leave an audience thinking; it should seem relevant and

contemporary to some extent. Behind this I catch the subtext that though

Japanese directors are right to avoid shock tactics, they could attempt a bit

more contemporary relevance.

Much of the opera produced in Japan relies on the enthusiastic contributions

of amateur and semi-professional choruses: indeed it is the desire of such

groups to be involved in opera that often sets the ball rolling, as in the

“community opera” system of which Chofu is part. One of the problems with

this, I suggest to Mastrangelo, is that the model massively favours operas with

a big but not too tricky choral role, and in practice this usually means

nineteenth-century works. He agrees with my diagnosis of the situation, but I

feel he doesn’t see it as a problem as much as I do. It is a “business

problem,” he maintains, slightly deflecting the question: “the Japanese

don’t like taking risks.” He suggests that European opera houses are often

“only half full” when modern works are staged; nevertheless, Japanese

audiences could slowly learn to appreciate such works. As I understand him, he

believes in a core repertoire of mostly nineteenth-century works, with Verdi at

the centre, which will slowly expand as the audience for opera is built up. The

closest he has come to straying outside the standard repertoire in Japan is

Cimarosa’s Matrimonio segreto. He is at heart a popularist, and I

detect no appetite for imposing modern works on audiences just because they

have been pronounced historically significant by critics or championed by a

small minority of music lovers.

I suggest that the Japanese and the British have a good deal in common when

it comes to opera: they tend to think of it as an essentially foreign entity,

best listened to in a foreign language. Mastrangelo strongly agrees, avoiding

any comment on British opera apart from assuring me that he loves Britten, “a

great composer.” “What of Japanese opera?” I go on, “should Japanese

opera companies schedule more works by Japanese composers?” His answer is a

surprisingly emphatic “no.” He explains that a lot of cultural familiarity

with opera is needed before great operas are produced; the implication is that

to Japanese composers - who, with one notable exception, only turned their

efforts to opera after World War II - opera is still too foreign a genre for

them to produce operas of a Verdian, international standard. They may have the

technical resources, but they don’t yet have the feeling. This may be true,

but I hear a lot of personal and national feeling in his answer: Mastrangelo

wants a future in which Japanese audiences will go on deepening their

understanding and appreciation of Italian opera in particular, and it is a

future in which he sees a significant role for himself.

After the scheduled interview is over, we continue chatting about opera, and

I put in a plug for Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei Tre Re as one of the

most unjustly neglected operatic masterpieces. Mastrangelo warmly agrees:

“Sì, sì! It is a beautiful, beautiful score! But …”

“But?”

“We could not get financial support for it in Japan.”

David Chandler