Now two estimable Greek-born performers offer an excellent and

varied selection of 18 David songs in performances that bring delight to ear

and mind.

Félicien David is not generally thought of as a songwriter. He is known

in the history books (e.g., Richard Taruskin’s thoughtful appreciation in

Oxford History of Western Music, vol. 3) for a single, large-scale

work: a “symphonic ode”—David’s term for a kind of a

secular oratorio, but with spoken narration in verse—entitled Le

désert (1844), about a caravan moving through a sandy wasteland and

stopping overnight at an oasis. Le désert is available in a

recording of a live performance (1989), with the Berlin Radio Symphony

Orchestra, on a Capriccio CD; a second recording, made in Paris,

appeared on the Naïve label in November 2014. Other CDs in the past three

decades have featured first recordings of David’s three piano trios; his

four string quartets; 11 of the 24 delightful one-movement pieces for string

quintet (quartet plus double-bass) that David published under the title Les

quatre saisons; some short works for violin and piano; and two collections

of piano pieces: Les brises d’Orient and Les minarets

(first published together under the title Mélodies orientales).

Best of all, for those among us who believe that the composer was one of the

most imaginative and influential of his generation, David’s operas are

finally getting the attention from performers that scholars such as Dorothy V.

Hagan, Morton Achter, and Hugh Macdonald have long urged: the comic opera

Lalla-Roukh, touching and witty by turns, on the Naxos label, and his

one grand opera, Herculanum. The latter, in a recording that features

Véronique Gens and Karine Deshayes, appeared in September 2015 on the

Ediciones Singulares label, as no. 10 in an “Opéra

français” series. That series of opera recordings is sponsored by

the Centre de Musique Romantique Française, an admirable

organization—based at the Palazetto Bru Zane in Venice—that has

helped fund most of the recent David recordings, including the present song

recital. Herculanum is also going to get its first staging in nearly a

century and a half: at Wexford Festival Opera, in Ireland (October-November

2016). Amazing to see a forgotten composer getting attention like

this—and the attention is extraordinarily well deserved.

Sample Track: Félicien David — “Le nuage”

The songs on this CD—dating largely from the late 1830s and

1840s—show remarkable range in mood: from tender confessions of love

(“J’ai peur de l’aimer”;

“L’amitié”) and reflections on the transience of human

life and sorrows (“Le nuage”) to sharply contrasting genre pieces

(the folk-Italian “Saltarelle”; a barcarolle entitled “Le

pêcheur à sa nacelle”; a soldier’s song, “En

chemin”—i.e., “Let’s hit the road!”; and the

lullaby “Dormez, Marie”). Two of the songs set, very effectively,

poems by Théophile Gautier that vocal fanciers know much better from

versions by Berlioz (“Reviens, reviens”—Berlioz’s

“Absence”—and “La chanson du

pêcheur”—Berlioz’s “Sur les lagunes”). Most

of the songs are strophic, but David sometimes enriches the piano accompaniment

in the second and later strophes. A few create substantially different music

for the final strophe (“Adieux à Charence”) or are

through-composed and intense, ignoring the meter and rhyme of the verse in

order to create a kind of operatic scena or accompanied recitative

(“L’océan: méditation”). Aside from Gautier, the

poets are all forgotten figures today: some were personal friends of the

composer (e.g., Emma Tourneux de Voves), but others were widely published at

the time, e.g., Charles de Marecourt, Marc Constantin, and Eugène

Barateau.

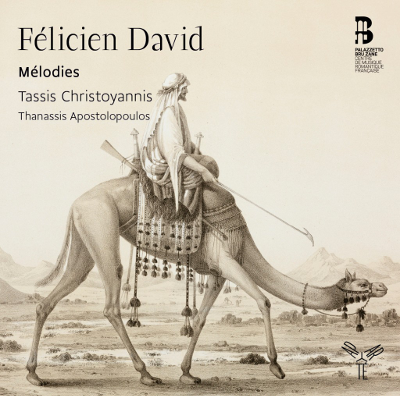

Most distinctive are two songs to texts written in the voice of a Middle

Eastern man. “Le tchibouk” draws its title from a word indicating a

long-stemmed Turkish pipe. The song quickly reels off a host of stereotypical

images of Middle Eastern life: the curling bluish smoke that rises from the

pipe, the hazy feeling that smoking the pipe induces, the coffee’s

fragrant aroma, the gracious movements of Fatma the dancing-woman, and the

attentions of ma brune amoureuse (“my dark-complexioned

lover”).

Even more specific and characterful are the verbal images in “Le

Bédouin,” a song whose poem was described by its author, Jacques

Cognat, as “imité de l’arabe” (i.e., in the style of an

Arab poem). The character who sings it, a Bedouin Arab, urges his camel (well,

we have to figure out that it’s his camel—the Bedouin calls it

“my faithful friend”) to fly with him across the desert “like

a gazelle,” and he compares the animal’s swaying to that of

“an enticing dancing-woman.” As the song proceeds, the man shows

himself to be full of yearning but also religiously devout: “In

anticipation of seeing me again, my beloved has put kohl around her lovely

eyes. . . . [Refrain:] Allah, grant the true believer [i.e., me] a safe

journey. You alone are wise, and I am a Muslim!” David and Cognat had

lived for a time in Egypt during the early 1830s as members of the

Saint-Simonian movement, a utopian-socialist movement that sought, among other

things, to modernize the educational system in Egypt and to persuade Egyptian

officials to cut a canal through the Isthmus of Suez. It is perhaps for this

reason that poet and composer created a song that, quite unusually for that

time, conveys in sympathetic terms the desires, travails, and modest lifestyle

of an Arab desert-dweller. (Regarding the Suez project: the Saint-Simonians

believed that a canal would enable the major world nations to become more

interdependent economically and that this would make them less likely to

wage war against each other. The Suez Canal would finally be built some

thirty-five years later by governments and banking organizations that gave

little or no credit to these foresighted thinkers.)

The music of “Le tchibouk,” with its bolero-like rhythm, may

seem more Spanish than Arab in style, but it is undeniably attractive.

“Le Bédouin” uses a quasi-Middle Eastern style that David made

famous in Le désert and that other composers, such as Bizet and

Delibes, soon copied. Most notable here are frequent pounding

chords—which suggest the beating of a drum—and some subtle touches

of modality.

The translations in the booklet, by Mary Pardoe, are generally skillful and

communicative. But she seems not to have understood that the “loyal

friend” in “Le Bédouin” is a camel rather than, say, a

male servant. Several times she even changes a plural verb to a singular (e.g.,

“volons” becomes “let me fly”), missing the basic point

that the Bedouin and his camel are inseparable companions.

The baritone, Tassis Christoyannis, has sung such roles as Germont

père and Don Giovanni at major opera houses in France and

Germany. He applies an impressively wide range of colors to this repertoire.

The voice is always fully supported, with a wondrous legato. The high range is

silky-smooth, yet the voice expands gratifyingly in the more emphatic songs.

Christoyannis nicely elaborates on the flamenco-like vocal cadenza at the end

of “Le tchibouk” and throws in a high note at the very end of the

song: a spontaneous-sounding and appropriate touch. His pronunciation is

remarkably fine for someone born outside of France, though I caught some

slightly problematic vowels (the e in “sera” and the nasal i in

“étincelle”). Throughout the disc, the pianist, Thanassis

Apostolopoulos, gives fine support, relishing the occasional moments of more

elaborate figuration.

Despite the riches on display here, numerous other equally fine songs had to

be excluded. A second CD of David’s songs, just released in France (on

the Passavant-Boutique label), offers many of the same items but also some

different ones, including the marvelous “Tristesse de

l’odalisque.” The singer on that CD, Artavazd Sargsyan, is a young,

award-winning lyric tenor—and apparently French-born, to judge by his

exquisitely comfortable handling of the texts. He takes slightly faster tempos,

ably seconded by a highly responsive pianist, Paul Montag. Still, nobody has

recorded one of my favorites: “Sultan Mahmoud” (to words by, again,

Théophile Gautier). The score can be easily found in David Tunley’s

indispensable six-volume anthology Romantic French Song, 1830–1870

(Garland Press, 1994).

Ralph P. Locke

Ralph P. Locke is Professor Emeritus of Musicology at the University of

Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. His books include two from Cambridge

University Press: Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and

Musical Exoticism from the Renaissance to Mozart. A version of the

review printed above originally appeared in American Record Guide.