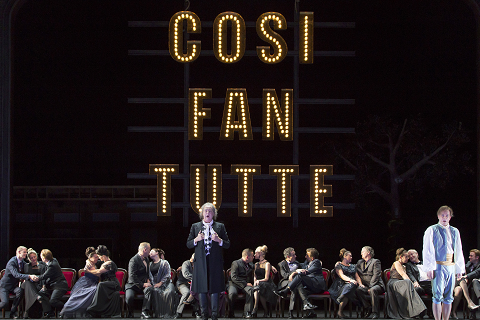

In case we don’t get it - and, perhaps, to guard against politically incorrect sexism - designer Ben Baur’s huge neon sign, Così fan tutti, looms

didactically and disapprovingly over the closing scenes.

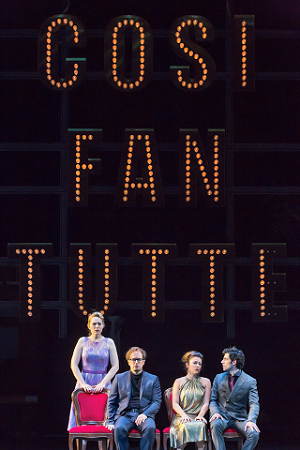

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

But, back to the beginning, which in fact is the ‘end’ - though not T.S. Eliot’s eternal wholeness - as five characters in elaborate period costume are

encouraged by a master-of-ceremonies to accept the audience’s applause with self-congratulatory zeal and faux obsequiousness: the full eighteenth-century

curtain-call monty.

There is a dash of unintentional irony, perhaps, given that at Covent Garden of late, the first-night call seems to have become an opportunity to hurl

obligatory boos at the director and designer. But, more than that, bringing the ‘cast’ in front of the curtain, into the small space which (as the

Anglo-Irish dramatist and critic Dion Boucicault wrote in 1889) belongs to both the stage and the auditorium, placed these singers/actors in a liminal

space between the characters they represent and their real selves.

And, the conduit between reality and artifice was further strengthened by the arrival of the ‘real’ cast in the aisles of the auditorium itself, dressed in

contemporary attire and flapping their ROH programmes as they anxiously sought to locate their allocated seats. Presumably in these fashionably tardy

fashionistas we were supposed to recognise ourselves; and so here, and at other times, the house-lights rose, to ensure that we didn’t miss the point that

this show is about ‘us’.

Leaving their belles behind, Ferrando (Daniel Behle) and Guglielmo (Alessio Arduini), awkwardly negotiating the knees of those seated in the front row of

the stalls, clamber onto the front-stage to join Don Alfonso (Johannes Martin Kränzle) - the latter no longer an ‘old philosopher’ but a

stage-manager/impresario who retains his period costume and, donning a black high-crown hat, all too often resembles the Witch-finder General.

Gloger and Baur then take us on a time-journey which lurches back and forth through the ages, from the Garden of Eden to behind-the-scenes mechanics of the

very opera that is unfolding before our eyes. The allusions - cinematic and cultural, theatrical and theological - raise interesting questions, and to

encourage us to reflect and relate we are consistently made aware of the self-conscious theatricality before us, as stage-hands in dungarees and doc

martins stamp through proceedings, hoisting ropes, shifting sets and carrying out Don Alfonso’s commands.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Daniel Behle as Ferrando, Alessio Arduini as Guglielmo, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

The histrionic departure of the two men takes place on a replica of the set of that timeless classic of repressed emotion, Brief Encounter,

complete with mist-shrouded buffers, hanging nineteenth-century clock and a platform peopled by a crowd of Celia Johnson-Trevor Howard couples clutching

each other in desperate duplicate.

Dorabella (Angela Brower) and Fiordiligi (Corinne Winters) first encounter the minimally masked men in a swish cocktail bar framed by Moulin Rouge

-style cabaret lights. A wisp of a moustache suffices to convince the girls that they’ve never before met the two charmers in skinny ties and drainpipe

trousers. Sabina Puértolas’s Despina - a cynical bartender rather than saucy soubrette - shakes a mean cocktail and delivers ‘In uomini, in soldati,

sperare fedeltà?’ with panache worthy of Sally Bowles, atop the bar, astride the bar-stools, pausing only to whip out a blackboard on which to instruct the

ladies in lessons of love - in case we’d forgotten that the opera’s subtitle is ‘ossia La scuola degli amanti’. Fun and frivolity were largely dispensed

with, though, and as the colour scheme faded from shocking pink to flat grey at the end of the scene (Bernd Purkrabek’s lighting is beautiful throughout),

the words uttered by Don Alfonso upon his entry, ‘what a sad and silent atmosphere’, seemed apposite. The gloom escalates and by the Act 2 duet which marks

Fiordiligi’s capitulation, ‘Fra gli amplessi’ the storm-clouds are descending, lowered from the flies by Don Alfonso. When Despina’s blackboard later

re-appears, her chalk scribbling, ‘Amor cos’è?’ assumes an accusatory, cynical tone.

© ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

© ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Next stop on our time-travel adventure is the Garden of Eden, complete with fallen apples hastily strewn by a stage-crew caught on the hop, and a

serpent-twined tree atop a rounded mound - whose steep slant subsequently provides a convenient ‘slippery slope’ down which the near-errant lovers can

slide. When Despina arrives with her magnetic cure for the arsenic-imbibing men, she resembles a biblical prophet who’s wandered in from the wilderness.

ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

During Act 2 we are led behind and before the curtain, venturing backstage and deep into the bowels of the theatre, where Don Alfonso and Despina smoke

cigarettes amid the detritus of dismantled props. Ferrando and Guglielmo now don stock oriental garb - high boots, salvars and turbans - so, fittingly, we

visit the costume department and as the girls spin mannequins it’s made clear that Fiordiligi and Dorabella are fully aware of the true identity of their

‘Albanian’ suitors - a problematic directorial decision for when Dorabella removes Guglielmo’s shirt she has no doubt, or qualm, about her own disloyalty

and it’s not clear who is being ‘seduced’. An interesting twist, perhaps, but one which robs the final ‘revelation’ of its relevance and piquancy.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, © ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Angela Brower as Dorabella, Corinne Winters as Fiordiligi, © ROH. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

In a recent interview (Guardian), Gloger commented, ‘Every director of Così fan tutte has to deal with the question of why the women don’t recognise their lovers through their

disguises, especially since they get right up close to them … [b]ut if the women are led into a theatrical, imagined space at the very beginning, and if

they are seduced into believing fictions, then this contradiction no longer applies’. This suggests that the director thinks that this, or indeed any,

opera is ‘real’. Whatever happened to that quintessence of theatre, especially opera, the suspension of disbelief - Shakespeare’s ‘imaginary puissance’?

Whatever. We are duly led through an exquisite eighteenth-century bucolic tableau, down into some shabby green rooms, arriving eventually in an auditorium

which presents us with a ‘reflection’ of ourselves, as a line of theatre-goers assembles for Don Alfonso’s ‘Tutti accusan le donne’.

Johannes Martin Kränzle as Don Alfonso. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

Johannes Martin Kränzle as Don Alfonso. Photo credit: Stephen Cummiskey.

The cast of young singers - billed as ‘up-and-coming - are unanimously good, though on occasion they are almost felled by the fatal flaw in this

production, conductor Semyon Bychkov’s snail-like tempi. It was as if Bychkov was so concerned, admirably, to ensure that we heard every instrumental

gesture with utmost clarity, that he forgot that he was not painting a picture but a sculpting a drama.

Winters’ Fiordiligi is indeed as ‘steady as a rock’ vocally: she has a bright, ringing top and she agilely leapt through ‘Come scoglio’. But ‘Per pietà’

was so sluggish that I half-expected to hear a hectoring cry, ‘For pity’s sake, get a move on!’

Ferrando’s ‘Un'aura amorosa’ was similarly robbed of its emotional depth by the listless tempo, which was a real pity as Behle exhibited a beautifully

sweet and light tenor throughout. He just about coped with Bychkov’s weary pace, but only by reducing his tenor to an almost-whisper in places - the pianissimo was impressive, but the overall effect was to suggest an ambiguous fine-line between emotional tenderness and frailty.

Angela Bower’s Dorabella was rather under-directed. Gloger had apparently decided that the usual hysterical mock-heroics of ‘Smanie implacabili’ were ill-suited to his conception but he did not know what to put in their place, and some table-top

antics and arm-swinging did not fill the gap.

Alessio Arduini suffered similarly as Guglielmo, lingering in Ferrando’s shadow dramatically, but Arduini has a strong baritone and made a good stab at

conveying a credible and independent character.

Sabina Puértolas as Despina. © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Sabina Puértolas as Despina. © ROH Stephen Cummiskey.

Johannes Martin Kränzle showed a good sense of timing and stage-craft, and his baritone is both full-bodied and fluid. It wasn’t Kränzle’s fault that this

Don Alfonso was hardly a figure-of-fun; indeed, by the end he seemed a rather smug and self-satisfied nasty-piece-of-work. Sabina Puértolas has quite a

weighty soprano and this Despina was well-sung but rather hostile and unforgiving towards the duped duo.

Gloger’s meta-theatrical exploits are all very sophisticated, and not without wit and wisdom, but often they are out of kilter with what the music is

saying - and, in fact, with what the libretto itself speaks. When Despina sings to the ‘ladies’, lamenting her own exclusion from their feminine romantic

indulgences, the two girls are not actually on stage; the two men may be dressed as West-End wide-boys from the 1950s but their lovers’ can’t tell whether

they are ‘Wallachians or Turks’. It might have been better to dispense with Da Ponte completely and start from scratch; it certainly would have been more

coherent.

Beethoven may have lamented that in Così Mozart had squandered his genius but to complain that the work is a frivolous fantasy seems to miss the precise point of the opera. The scepticism of

Così may seem attuned to our own disenchanted age of disbelief, but surely to appreciate Mozart’s exquisite blend of irony and sincerity we need to wholly

abandon verisimilitude, suspend our disbelief and enter the fantasy created by Da Ponte - a world both impossibly absurd and authentically reflective

of its time. We may charge the librettist with superficiality and simplification, but Mozart’s music delves deeper and restores truth in all its

complexity. Mozart’s score reveals the poetry - the beautiful poignancy - of the inexorable co-existence of hope and doubt in the human heart. Gloger’s

Così

is simply too clever for its own good.

Claire Seymour

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Così van tutte

Fiordiligi - Corinne Winters, Dorabella - Angela Brower, Ferrando - Daniel Behle, Guglielmo - Alessio Arduini, Don Alfonso - Johannes Martin Kränzle,

Despina - Sabina Puértolas; Director - Jan Philipp Gloger, Conductor - Semyon Bychkov, Set designer - Ben Baur, Costume designer - Karin Jud, Lighting

designer - Bernd Purkrabek, Dramaturg - Katharina John, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 22nd September 2016.