After requesting permission from Maestro Sesto Quatrini to adopt a more modern plotline, the cast frantically flipped through newspapers scattered on the stage floor, seeking a plot less antiquated than that of Rossini’s La Cambiale di Matrimonio.

Opera suffers from a lot of “old-fashioned” traditions. Many of the more traditional classical or Romantic storylines center on some pretty disturbing themes, even when the outcome is comedic. Somehow as opera audience members, we give a cursory glance to these premises in order to enjoy the music; we favor the comedy in a situation that’s otherwise disturbing, even if it’s a story about a girl being sold into marriage with a man twice her age or a farce about a servant being relentlessly sexually harassed by her older employer. In La Cambiale, the plot centers around Tobias Mill, father to Fanny, who wants to sell his daughter in marriage to a rich Canadian, Slook.

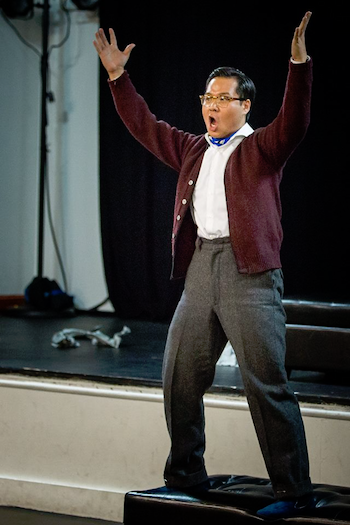

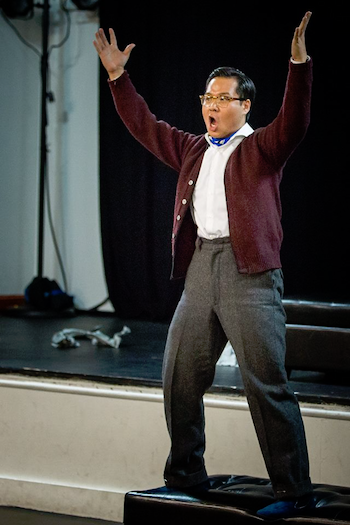

Suchan Kim

Suchan Kim

Should we ignore these premises, though? Bare Opera takes a moment of reflection to question our complacency, reading real headlines from New York Times articles from the past two weeks. The cast managed to read three headlines, all of which highlighted different instances in which women and girls were trafficked or killed for resisting forcible marriage.

A brief search into the New York Times coverage of girls in forced marriages leads to dozens of hits. One article from July of this year told the story of Zahra, a young girl who liked performing in her school drama and got chosen to do a juggling act as part of an educational circus that came to her school. When her father decided to remarry, Zahra became part of the dowry, and as a sixth grader, was married off, and then about two years later, died when her husband’s family set her on fire. She was four months pregnant when she died, and the soles of her feet were the only part of her body that was unburned.

So how funny is it to watch an opera about a young girl being sold (or mortgaged, a word that comes up a lot in the libretto) into marriage to a man she has never met?

The cast gave up on their quest for a more modern storyline, since it was clear a story about a girl being sold was not an old-fashioned story at all, and got on with the music. After the moment of sobriety during the pre-show announcement, the music swept away any moral misgivings, especially since Bare Opera kept the production thoughtful and reflective, while still serving the comedic outlandishness inherent in Rossini’s work.

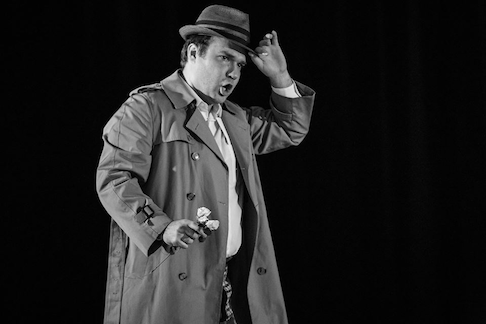

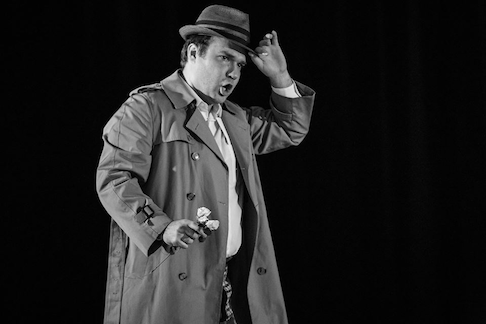

John Allen Nelson

John Allen Nelson

Sesto Quatrini is an energetic and communicative conductor, eliciting a gorgeous palette of sounds from a truly exceptional group of musicians. The ensemble was incredibly tight and harmonious, especially for a group that is unlikely to play together regularly.

The cast also shines in a very creative and exciting staging of Rossini’s first opera, composed in a few days when he was only 18 years old. La Cambiale has all the hallmarks of a Rossini opera, and a lot of the characters tend to be a little one-dimensional. However, this fine cast manages to eke out different shades of characterization from their roles, helped along by the direction by Cecilia Ligorio, which provides many moments of authentic delight for the audience. There was no set to speak of, and the production plays between a traditional stage space and a more intimate in-the-round style of staging. However, no one seemed to notice the paucity of the production elements. Indeed, it has been a long time since I’ve sat among such a rapt audience, especially for a very traditional work. The energy of the crowd was palpable, and several moments elicited genuine gasps and giggles.

Kirsten Scott slips easily into her role of Clarina after donning her Executive Producer cap. She brings Clarina to life in a very sexy but down-to-earth portrayal with a well-sung and sparkling aria in the latter half of the opera. John Allen Nelson portrays the buffoonish Slook with a more casual, less caricatured air, with a demeanor which is much more sinister than the usual blustering buffoonery adopted by many singers in this role. He plays Slook as a man surprised to hear that he’s being refused, and surprised that a woman would even have an opinion at all. Nelson has a full, easy sound, and is a pleasure to hear and watch.

Liana Guberman and Sungwook Kim

Liana Guberman and Sungwook Kim

Liana Guberman (Fanny) has the perfect bel canto voice, supple and lush with all the brilliance needed for Rossini. She plays Fanny not as a silly young girl, but as a woman genuinely wounded by her father’s betrayal. There’s nothing frenetic about Guberman’s portrayal; in fact, it even tends towards heartbreaking, particularly in some moments during her duet with Slook. Her huge aria at the end of the opera is a high point of the production, especially in conjunction with an incredible performance by dancer Daisy Ranson Phillips, who uses Rossini’s music to punctuate her bodily movements.

Suchan Kim (Tobias Mill) magnetizes the audience to him throughout the evening, with a sumptuous baritone voice and precisely communicative Italian. He is wonderfully funny without ever becoming cartoonish, and sustains a level of energy in both voice and deportment that left me exhausted just watching him.

The entire cast (including Sungwook Kim as Edward Milfort and Colin Whiteman as Norton) perform with such joy that it’s impossible not to go along with them. They don’t give into character stereotypes or devolve into farce, even where it would have been easy to do so. There’s something naturalistic and terribly believable about their performances, yet each singer retains the exuberance necessary to keep the audience engaged.

Opera is trying so very hard to be cool again, giving into hackneyed techniques like liquoring up its audience or offering up scantily clad soprani. Bare Opera doesn’t need to try to be cool, because they already know they are cool. The sheer joy they take in performing Rossini’s work is infectious. This cast, crew, and production leave the audience breathless and exhilarated. Opera may be old fashioned—maybe—but Bare Opera knows it’s as relevant today as it was 200 years ago.

Alexis Rodda

![Kirsten Scott and Colin Whiteman [Photo by Gustavo Mirabile]](http://www.operatoday.com/bareopera2.png)