A crumbling freeway flyover juts jaggedly into a black nothingness. As Manon collapses into her desert surrounding, so the terrain itself sinks into abyss.

Puccini’s third opera was premiered in Turin on 1st February 1893 - just over a week before the first performance of Verdi’s Falstaff in Milan -

and the work’s blending of obvious debts to Italian Ottocento lyric traditions and an engagement with Wagner’s innovative harmonic language ensured that it

was an unqualified success, with contemporary critics declaring Puccini the foremost composer on the Italian scene.

However, to present-day audiences, Puccini’s opera can seem less an evolutionary development of the past, and more a strikingly modern statement. And,

despite the undeniable beauty of the score, after its initial triumph the opera’s subsequent critical reception has at times been characterised by

disquiet: a sense that there is something insalubrious and ‘not quite nice’ about the opera. Kent and his designer Paul Brown wholly embrace the

dark side of Puccini, and drag his nineteenth-century good-time-girl-gone-bad into the modern world.

Their dystopian twilight zone is, however, somewhat at odds with the sensuous eroticism of Puccini’s score. Admittedly, when mired in the

bleakness of Act 4, it is difficult to find a redemptive note in Manon’s demise - a death which she fights to the last: ‘No! non voglio morir …’ But, it is

passion and not pointlessness which lies at the heart of this opera, and it is this essential ‘soul’ which Kent neglects. There is a gratuitous

quality about Manon’s suffering; it signifies nothing but itself.

Fortunately, conductor Antonio Pappano is in the pit to restore the opera’s impassioned pulse and pump emotional life-blood through its veins. On the first

night of the run, his crafting of the musico-dramatic ebbs, flows and lurches was masterly and utterly convincing. Pappano has an innate feeling for the

long lines which expand so effortlessly. The constant shifts of mood seem entirely natural. The Prelude opened with a searing and slashing slash

of the violins’ knife but before we knew it the mood had lightened and we were swept along by the rich busyness of the opening scene. The intermezzo between Acts 2 and 3 presented a stunning array of emotional colours and musical ambiences: there was a tremendously sense of

spontaneity and directness, as Pappano plunged the depths of the drama. The ROH Orchestra held nothing back, but the playing was never anything but

elegant. Indeed, one of the most striking features of the performance was that while the ostentatious romantic climaxes were relished there were moments of

great delicacy too. The series of chords that open the final Act were an unnerving shudder of death; mid-way through this Act, the theme which represents

the protagonists’ love - and which had blazed so triumphantly at the end of Act 3 - was heard again, a shimmering reprise, a symbol of a hope now faded and

elusive.

ROH Chorus, Act 1. Photo credit: Bill Cooper

ROH Chorus, Act 1. Photo credit: Bill Cooper

Kent and Brown are more mundane, the brutality of their realism quashing any lingering romance. The square and inn of Amiens, the setting for Act 1, are

jettisoned for a flashy apartment block and a gambling casino. Thus, a light-hearted evening gathering in the village - denim-clad teenagers whizz around

atop wheelie bins and adolescents bounce about exuberantly led by Luis Gomes’ ebullient, open-hearted and warm-voiced Edmondo - is set against an

iniquitous den of baize gaming tables and one-armed bandits, intermittently lit with a lavish glare by lighting designer Mark Henderson.

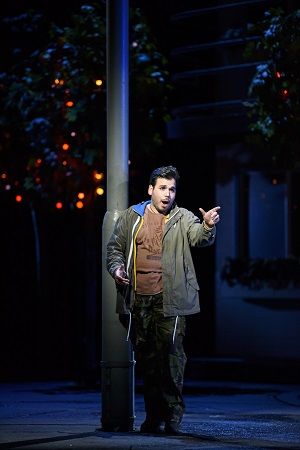

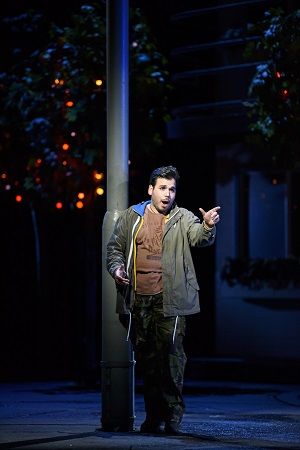

Luis Gomez as Edmondo. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Luis Gomez as Edmondo. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Manon arrives in a silver SUV, a picture of innocence in her floral frock. But, it’s but a short step from urban ingénue to Geronte’s peacock in a ‘golden

cage’. And, in Act 2 Manon finds herself in an opulent but lurid boudoir of cerise and purple, in which time stands still and Manon herself is frozen as

one of Geronte’s riches.

There is nothing intimate about this ‘private’ space which is the setting for Act 2; it’s a peep-show booth in which Manon preens her hair, applies her

elaborate make-up, is pleasured by the lesbian Singer - a role ably sung by Emily Edmonds - and gyrates and squirms for the delectation of a posse of

geriatric, masked voyeurs, who, with their backs to us, enjoy a soft-porn display during the Act 2 pastorale which a cameraman records on a

hand-held camera - presumably for YouTube dissemination.

Levente Molnar as Lescaut, Sondra Radavanokvsy as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Levente Molnar as Lescaut, Sondra Radavanokvsy as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Kent’s trope, though, is not irrelevant. From her first entrance in Act 1, Manon is presented through the gaze of others, principally Des Grieux. When

Lescaut’s cries to the Innkeeper catch his attention, he raises his eyes and sees Manon: the libretto tells us that ‘facendo un gesto di meraviglia, la

osserva estatico’ (making a gesture of amazement, he looks at her ecstatically), and with a cry, ‘Dio! Quanto è bella’ (God! How beautiful she is), he

hides from view in order to espy her. His gaze guides us; we first see Manon through the filter of Des Grieux’s rapture and wonder. Our gaze is bound with

his and that of the other characters on stage, including the assembled line of dirty old men. In Kent’s reading, our ‘heroine’ is aware that all eyes are

on her, and is complicit in the performance of her personae.

Yet, whether the director manages to turn Manon from a passive object of desire into an active subject who can manipulate her own identity within a

prescribed system is another matter. Urging her to escape, Des Grieux cries ‘Bring only your heart’ as Manon stuffs Geronte’s jewels into a pillow case;

her tardiness is her downfall - seemingly captivated by the room’s treasures she succumbs to its claustrophobic clutch and is arrested.

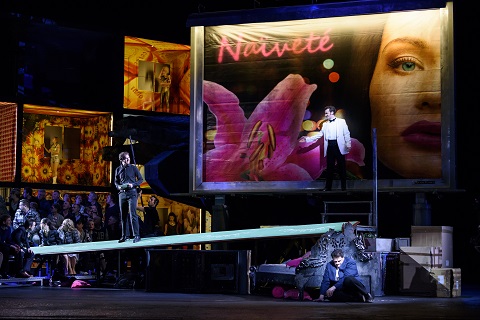

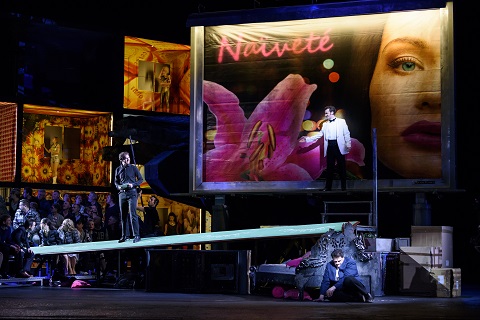

David Shipley as Sergeant, Nicholas Crawley as Naval Captain, Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

David Shipley as Sergeant, Nicholas Crawley as Naval Captain, Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

In Act 3 the dock-side square at Le Havre, through which the humiliated prisoners process on their way to deportation to the US, becomes in Kent’s hands

the studio of a TV reality-show, compered not by a police sergeant but by a tuxedoed MC. The girls are taken to an Amsterdam-style red-light district where

sex slaves are trafficked abroad by pimps.

And, though there are, during the proceedings, some front curtain projections of text from the 1731 novella by Abbé Prévost on which the opera is based,

Puccini’s Act 4 crucially rejects the context provided by Prévost's narrative, and excludes the months of contentment spent by Manon and Des Grieux in New

Orleans. So, Kent plunges us into misery - and pushes Des Grieux and Manon through a gaudy advertising hoarding onto a highway of broken dreams.

In the title role, Sondra Radvanovsky does not always appear a natural fit for Kent’s soft-porn star protagonist but her warm soprano wins our sympathy,

and she crafts many a winning lyrical line, counter to the staging’s coldness. Radvanovsky acts and moves well. Her vibrato was quite wide and in

the first two Acts she exhibited a tendency to slide onto notes - and struggled to hold onto the note when she’d got there - but she succeeded in conveying

both the warmth and vulnerability of Puccini’s creation. Manon’s Act 4 peroration, ‘Sola, perduta, abbandonata’ - in which Puccini thrusts Manon into our

prying gaze (in contrast to Prévost’s discretion) - was a touching rebellion against death and against the society which seeks to punish her. In Manon's

last vocal moments, Radvanovsky found incredible, if waning, sweetness, ensuring that we understood the dreadful regrets of the dying woman. Radvanovsky crafted the arching cries, the fragmented contours, and the truncated repetitions, with acute theatrical insight and technical skill

- she moved, indeed leapt, effortlessly, from the top to the bottom of her range.

Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux and Sondra Radanovsky as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Aleksandrs Antonenko as Des Grieux and Sondra Radanovsky as Manon Lescaut. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko was vocally assured as Des Grieux; he fired his big guns with lyric aplomb - ‘Donna non vidi mai’ was impressively

expansive - and if some of the risks he took at the top end did not come off, then at least he was impassioned in his essays, and his Act 4 emoting was

superb. Antonenko is not equally assured across his range, but this helped to convey an impression that his Des Grieux combined vocal strength with vulnerability.

Eric Halfvarson as Geronte de Revoir. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Eric Halfvarson as Geronte de Revoir. Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Eric Halvarson was a cunning Geronte de Revoir, not afraid to make an ugly sound if it served the drama. His elderly roué had strong dramatic presence, and

the text was cleanly delivered. Levente Molnár was persuasive as Manon’s charming but unprincipled brother, Lescaut.

I left the theatre feeling that if Tosca was Puccini’s ‘shabby little shocker’, then Manon Lescaut was his depiction of shockingly cruel

injustice.

Claire Seymour

Giacomo Puccini: Manon Lescaut

Manon Lescaut - Sondra Radvanovsky, Chevalier des Grieux - Aleksandrs Antonenko, Lescaut - Levente Molnár, Geronte de Revoir - Eric Halfvarson, Edmondo -

Luis Gomes, Musician - Emily Edmonds, Dancing Master - Aled Hall, Singer - Emily Edmonds, Lamplighter - David Junghoon Kim, Sergeant - David Shipley, Naval

Captain - Nicholas Crawley, Innkeeper - Thomas Barnard; Director - Jonathan Kent, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Designer - Paul Brown, Lighting designer -

Mark Henderson, Movement director - Denni Sayers, Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Royal Opera Chorus.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Tuesday 22nd November 2016.