Iago’s gesture of vehement vexation opens the drama with the shattering of

a symbol of deception and artifice that complements Iago’s masking of his

‘self’ - ‘I am not what I am’. Then, at the close of Act 2, Otello is

confronted by a mirror which reflects back at him a masked figure. Finally,

prone and emasculated, following a seizure brought on by Iago’s ‘proof’ of

his wife’s unfaithfulness, the Moor is himself wreathed with this mask by

his puppet-master. But, the destruction of this theatrical adornment at the

start of the opera reminds us, too, that Iago’s iniquity will be

exposed, as Shakespeare’s Iago himself foresees: ‘when my outward action

doth demonstrate/ The native act and figure of my heart … I will wear my

heart upon my sleeve/ For daws to peck at’.

Moreover, in placing Iago, rather than the eponymous Moor, centre-stage in

the initial moments, Warner foregrounds an equality of dramatic status

which mirrors Shakespeare’s text. Iago speaks by far the greater number of

lines and it is his compelling soliloquies which make the audience almost

complicit in the villain’s stratagems. And, in a letter to Boito, Verdi

described Iago as ‘the Demon who moves everything’, noting that ‘Otello is

the one who acts: he loves, is jealous, kills and kills himself.’ Despite

Otello’s titular status, in Warner’s production Jonas Kaufmann’s

introspective Moor and Marco Vratogna’s vengeful ensign are equal

participants in the tragic unfolding, in a production which embraces the

protagonists within a strong ensemble.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

That said, it was undoubtedly Kaufmann whom the multi-national audience had

come to see. And, tackling the role for the first time, he did not

disappoint. Otello’s fairly low tessitura suits Kaufmann’s tenor which has

baritonal resonances and he was pretty fearless in approach, holding

nothing back vocally at the challenging peaks. Otello’s fears were

passionately exclaimed in ‘Ora e per sempre addio sante memorie’; in

contrast, ‘Dio mi potevi scagliar’ was distressingly meditative - often the

barest whisper conveyed wistful introspection - though perhaps lacking a

full palette of colour. Kaufmann’s Act 1 duet, ‘Già nella notte densa

s'estingue ogni clamor’, with Maria Agresta’s Desdemona was particularly

beautiful, though in general I wasn’t entirely convinced by the chemistry

between the doomed lovers; here, as they narrated the tale of their

courtship, their desires seemed aroused as much by their own vocal

mellifluousness as by their memories of romance and adventure.

Kaufmann’s Otello is no commanding hero, though. His ‘Esultate!’ is not a

thunderous entrance that would silence a storm; rather, this Otello

surfaces within the crowd, though the victor’s cry rings with bright

strength. Moreover, if he does not convey imposing ascendancy then neither

is Kaufmann’s Otello petulant, despite the fact that Boito has his ‘hero’

repeatedly burst into rage. Indeed, the brevity and orchestral power of our

introduction to Otello suggests that, in Verdi’s eyes at least, he is a

figure of more than simply military might and physical power.

Boito and Verdi have created not a ‘noble savage’ - whom Shakespeare’s

contemporaries might have considered overcome by his innate bestial

sensuality (and Kaufmann is not blacked up, which is unproblematic given

that Boito does not draw much attention to the Moor’s race and colour) -

but a man of solipsistic susceptibility, which Kaufmann’s quiet

anguish captures perfectly. His fragile pianissimos become an apt

representation of the linguistic fragmentation of the text’s ‘Othello

music’, as the grandiose imagery of ‘Olympus-high’ oceans ruptures into

stuttering banality - ‘ Pish! Noses, ears, and lips.’ Verdi cannot disrupt the beauty of the vocal line in the way that Shakespeare deconstructs the linguistic metre and syntax, and so, in this way, Kaufmann’s reticence becomes almost a rhetorical strategy.

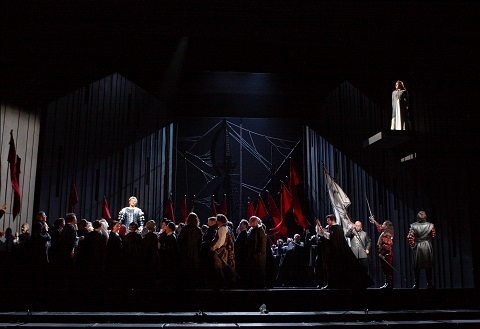

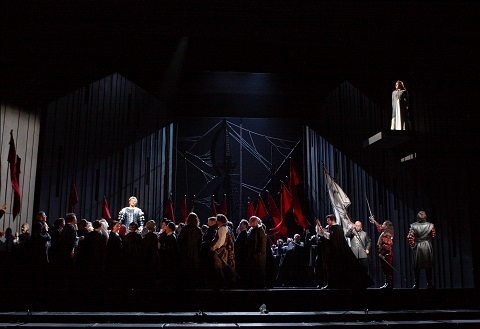

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

And, it is a strategy echoed in Boris Kudlička’s minimalist designs which

profess Warner to be more concerned with the internal than the external

workings of the drama. The walls of Kudlička’s ‘black box’ slide inwards,

their trellis-tracery allowing figures to eavesdrop furtively, while also

elegantly referencing Moorish filigree lanterns. We are presented with a

psychological chamber in which we seem to explore what Melanie Klein termed

‘projective identification’: that is, the projection onto others of

feelings that inspire suffering or thrill within a subject. If we view the

opera in this way (as Richard Rusbridger does in his article in the International Journal of Psychoanalysis , February 2013), Warner’s opening gesture identifies the storm with the

emotional turmoil in Iago’s mind, and not, as in Shakespeare’s play, the

ensuing breakdown of natural, civil and domestic order.

Marco Vratogna (Iago). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Marco Vratogna (Iago). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Indeed, Marco Vratogna’s Iago is undoubtedly hellbent on Hades. There is

nothing clandestine about his malignity, though I’d suggest that in fact a

little more serpentine slipperiness would not go amiss: after all, his

‘honesty’ as perceived by those around him, must be credible. Vratogna has

a strong upper register - such as can provide propelling drive in the

Brindisi - but his occasional hoarseness fittingly reminds us that Iago is

a rough soldier, whose coarseness may have inclined Otello to promote the

more urbane Cassio to be his lieutenant. That said, Vratogna’s

light-breathed insinuations floated into Othello’s ear with the elegance of

a lover’s discourse.

If Iago is ‘the Devil’, rejecting God in his Credo - ‘I believe that the

righteous man is a mocking actor both in his face and in his heart, that

all in him is a lie, tear, kiss, glance, sacrifice and honour’ - then

Desdemona is his antithesis, an angel of saintliness, whose innocence and

grace Iago is driven to violently expunge. There is little of Shakespeare’s

playfulness or feistiness in Boito’s characterisation. Maria Agresta, often

pushed to the hinterlands of the production, until the final scenes, sings

with a rhapsodic lustre and fullness of tone that perhaps betrays a

sensuality less than innocent, but her Willow Song and Ave Maria are

composed and restrained, an acceptance of the inevitable and a welcoming of

the hereafter.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello) and Maria Agresta (Desdemona). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jonas Kaufmann (Otello) and Maria Agresta (Desdemona). Photo credit: Catherine Ashmore.

The rest of the cast are by no means ‘secondary’. Frédéric Antoun’s Cassio

is elegantly persuasive but Iago’s duet with Cassio in Act 3 highlights the

latter’s narcissism and superficiality. Thomas Atkins’ Roderigo and Kai

Rüütel’s Emilia are finely drawn. A sense of Venetian grandeur is offered

by Sung Sim’s noble Lodovico and Simon Shibambu’s courtly Montano.

Pappano conjures blazing intensity from the ROH players. Not everything is

precise, but there is a visceral quality to both the orchestral and choral

climaxes which is countered by subtleties such as the string sonorities of

the Prelude to Act 3.

Warner’s vision does stumble at times: the arrival of the masted ship and

the extending of the high gangplank for Desdemona’s disembarking lack

refinement; the shattering of the winged lion seems cliched; and, perhaps

because there is a focus on the interior rather than the exterior, some of

the movement blocking, excepting the Chorus, is uninventive.

But, Iago’s greatest masterstroke is respected. He can literally turn white

into black: ‘So will I turn her virtue into pitch,/And out of her own goodness make the net/ That shall enmesh them all.’

And, so, in the final moments, the ‘black box’, inflamed by Bruno Poet’s

illumination, is made to contain a snow-white pearl - the white-upon-white

canvas of Desdemona’s doom. The sumptuous bed is, perhaps inevitably,

smeared with a painter’s flourish of red blood. This serves as a visual

emblem of the tragedy’s catalyst and its conclusion (but the neon ‘halo’ is

superfluous, surely?). For, it is the strawberry-spotted handkerchief which

is Iago’s prime tool of deception and it is this antique token of affection

which subsequently serves as an agent of truth, exposing his iniquity.

Thus, it is, paradoxically, a delicate symbol of overpowering destiny. As

Othello despairs, ‘Who can control his fate?’

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Otello

Otello - Jonas Kaufmann, Desdemona - Maria Agresta, Iago - Marco Vratogna,

Cassio - Frédéric Antoun, Roderigo - Thomas Atkins, Emilia - Kai Rüütel,

Montano - Simon Shibambu, Lodovico - In Sung Sim, Herald - Thomas Barnard; Director - Keith Warner, Conductor - Antonio Pappano, Set designer - Boris Kudlička,

Costume designer - Kaspar Glarner, Lighting designer - Bruno Poet, Movement

director - Michael Barry, Fight director - Ran Arthur Braun, Royal Opera

Chorus (Concert Master - Vasko Vassilev), Orchestra of the Royal Opera

House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Wednesday 21st June

2017.