Based on Goethe’s German-Romantic tale “The Sorrows of Young

Werther,” and sung in French with English surtitles, the nearly

three-hour production’s skeletal plot of boy meets girl; boy loses girl;

boy dies is opera at its compact best. Preferring not to gild the lily with

convoluted (albeit operatic) twists and turns, it delves more deeply into the

hearts and minds of its ill-fated characters, underscored by Massenet’s

stunningly gorgeous music brought to life by Tyrone Paterson leading the

Winnipeg Symphony Orchestra.

Last appearing onstage as Tonio in MO’s 2012 production of

Donizetti’s “The Daughter of the Regiment,”

Edmonton-born tenor John Tessier in the title role may quite rightfully may be

considered a Canadian treasure. He spun every lyrical phrase like fine gold,

first heard during his opening aria “O Nature, pleine de

grâce," performed with ease and capped by ringing high notes. His

showstopper: “Lorsque l’enfant revient

d’un voyage,” and later, a goose-bump inducing

“Pourquoi me reveiller” elicited well-deserved,

spontaneous applause with cries of bravo.

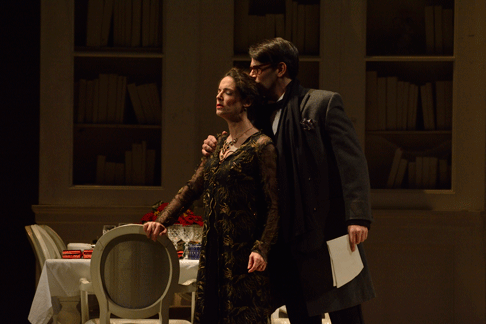

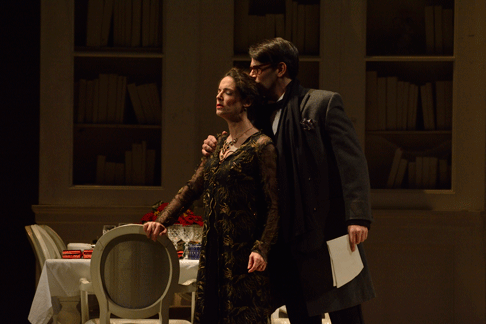

Lauren Segal (Charlotte) and Keith Phares (Albert

Lauren Segal (Charlotte) and Keith Phares (Albert

South African/Canadian mezzo-soprano Lauren Segal as Charlotte also created

a flesh-and-blood “angel of duty,” with her prismatic acting skills

revealing her character’s inner turmoil until her final climactic

“Ah!” after Werther dies in her arms. Segal’s rich vocals

also resonated during Act III’s “Va! Laisser couler mes

larmes,” that grew in dramatic intensity as she realizes the

poet’s path towards self-destruction.

Winnipeg-based soprano Lara Secord-Haid’s sparkling portrayal of

Charlotte’s younger sister Sophie captured the impetuous optimism of

youth, as she skipped and flitted about the stage with her effervescent

colouratura on full display during “Du gai soleil, plein de

flame.” But she also imbued her youthful character with subtle

nuance, creating a fascinating sub-text for her own tragic tale of love and

loss after Werther’s departure leaves her sobbing uncontrollably during

Act II.

Scene from Werther

Scene from Werther

Albert performed by American baritone Keith Phares proved solid and true,

besotted with his wife Charlotte, with his resonant voice clearly projecting

while providing steady ballast to Werther’s eloquent arias.

The cast also includes Le Bailli performed with gravitas by baritone David

Watson, and his whiskey-swilling village sidekicks, Johann (baritone Howard

Rempel) and Schmidt (tenor Terence Mierau). An ensemble of six children

(prepared by Carolyn Boyes) delivered a sweetly jubilant “Noel!

Noel,” that heightens the dramatic tension during the final

Christmas Eve scene with its twin messages of birth and death.

Having said all this, the production itself proved uneven. Hodges opted for

an overall slow-burn approach to the lead characters’ respective

emotional trajectories, allowing Werther’s love for Charlotte to first

smolder like ashes during Act I and II, before finally erupting into flames in

Act III. When the poet arrived to escort Charlotte to the dance in Act I, their

first encounter came across as more polite than passionate. His understated

reaction to hearing of Charlotte’s impending nuptials also did not

clearly read, despite his later, angst-ridden “Un autre est son

époux!"

It’s also difficult establishing a physical/emotional connection when

Charlotte herself is forbidden fruit, so duty-bound she refuses to even kiss

Werther until he is mortally wounded by his own hand. This created a strangely

distancing effect that a few embraces – no matter how furtive –

might have helped mitigate.

Still, other artistic choices were effective, including an added prologue

showing the death of Charlotte’s mother. This established the

opera’s overall themes, while also providing Charlotte’s motivation

for remaining stonily resistant to Werther’s ardent declarations of

love.

The 1920s-styled set on loan from Opéra de Montréal, with the

production itself originally created by Opera Australia appeared striking in

its simplicity, while also engendering fresh appeal. Nevertheless, sightlines

at times became challenging, and the “big box” style of set

visually dwarfed the opera’s sweeping themes of transcendent love,

despite its waving grasses just beyond the formal exits that beckoned of wild

nature and freedom like a siren song.

Effective lighting design by Bill Williams included a luminous moon under

which Charlotte and Werther fall in love during Act I, and relatively abrupt

fades during Werther’s key arias, which nevertheless focused attention on

the doomed poet as he hurtled toward his own death spiral for love.

Holly Harris

![Lauren Segal (Charlotte) and John Tessier (Werther) [Photo by R. Tinker]](http://www.operatoday.com/_TNK2645.png)