Guth’s and designer Christian Schmidt’s concept is more sentimental than

Imperial, but not without relevance and effect. During the overture - brisk

and airy under Robert Ticciati’s guidance - we enter a world of whimsy, as

a digital projection unfolds the adventures of two young boys playing amid

the woods and beside the lake in a rural idyll with more than a hint of

resemblance to Glyndebourne’s own grounds. The faux chivalry of

sword-fights with sticks takes a more sinister turn when the boys stalk

wildlife, one with catapult a-ready. A shot is slung, and a bloodied magpie

is the result - a betrayal of trust and of nature.

Unfortunately, first-night flickers and blackouts made the visuals even

more distracting from the musical prelude than might have been the case;

and, it’s not immediately clear that these two lads are the adolescent Tito

and Sesto, whose friendship will be so tensely tested in the ensuing

operatic narrative. This is not just a matter of realism - Richard Croft’s

Tito looking at least one generation ahead of Anna Stéphany’s Sesto - but

also because there is no clear link between the on-screen Elysian fields

and the post-eruption ashes of the land of Vesuvian shadows which form half

of the set. It is only in Act 2, when the conflicted Tito must decide the

traitorous Sesto’s fate, that the parallels crystallise: the two young boys

escape from the digital celluloid and clamber through the rough reed beds,

ghostly representatives of disloyalty and division, who haunt their

subsequent selves with disturbing memories.

Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

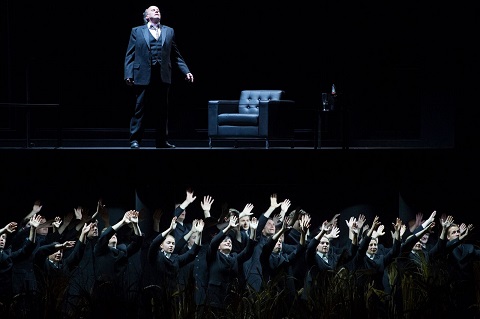

There is nothing Imperial about Schmidt’s split set: ravaged undergrowth -

presumably the foothills of the recently erupted Vesuvius, as lava rocks

and odds bits of furniture lay strewn - is juxtaposed with a grim, grey

modern corporate milieu which lies hidden above until the black projection

screen is lifted. There’s a lot of up and down, and upstairs/downstairs,

but Olaf Winter’s gloomy lighting is atmospheric and apposite, emphasising

the dullness and inertia of Tito’s political relationships and his own

disaffection with a power dependent on fear.

Guth’s Personenregie is not always credible. Vitellia cries ‘Come

here and embrace me,’ as she wanders off in the opposite direction from the

infatuated Sesto; ‘Come near me!’ Tito demands, as he and Sesto walk

backwards towards each other (tentatively, across an obstacle-strewn set -

which ironically almost wrong-footed some the production team during the

curtain calls), bump into each other and then lurch apart. When Sesto

refuses to divulge the reasons for his treason, Tito threatens his beloved

friend with a sickle, then uses it to scythe clumps of reeds which he

clutches to his chest. There is much synchronised choral semaphoring from

the ‘men in grey suits’ (both the gents and ladies of the Glyndebourne

Chorus being thus attired).

Vitellia (Alice Coote), Sesto (Anna Stéphany) and Publio (Clive Bayley). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Vitellia (Alice Coote), Sesto (Anna Stéphany) and Publio (Clive Bayley). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Fortunately, there is some excellent singing to distract us from the

irritating visuals. The withdrawal of the pregnant Kate Lindsay led

Anglo-French mezzo-soprano Anna Stéphany - originally intended for the role

of Annio - to step into Sesto’s shoes and her performance was simply

stunning. I missed Stéphany’s much-lauded Marschallin at the ROH (where I

saw a performance by the first cast), but I did admire her capricious Serse

in the Early Opera Company’s performance of Handel’s opera at St John’s

Smith Square last November. And, once again it was a true delight to enjoy

her exquisitely styled phrasing and expressive coloratura. The challenges

of ‘Parto, parto, ma tu, ben mio’ were met with ease, and the coloratura

was sweet-toned, as if overflowing with Sesto’s love for both Vitellia and

Tito - a love which was reflected in the beautifully played basset clarinet

obbligato. ‘Deh, per questo istante solo’, in which Sesto declares himself

deserving of death, vowing to take all the guilt upon himself, was equally

moving. Impressively, Stéphany made the role dramatically credible too,

plausibly treading the fine line between idealistic self-sacrifice and

all-consuming passion - a task made more difficult in a production where it

was not evident why anyone would fall so unreservedly under the erotic

spell of Vitellia.

The vengeful daughter of a deposed emperor who abuses Sesto’s love to gain

power and become Empress, Alice Coote’s Vitellia is clear ‘a baddie’ - a

gun-toting chain-smoker, she even has a purple coat. Less femme fatale than

a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown, this vituperative Vitellia

seems to slide into hysteria, even psychosis, when she holds a pistol to

Sesto’s head to convince him to murder Tito. No one could accuse Coote of

lack of commitment and this was a heroic effort, but she was vocally taxed

by a role which frequently lies too high for her mezzo. In ‘Deh, se piacer

mi vuoi’ she pushed her voice hard, as Vitellia dreams of being Empress,

but the result was sometimes squally. In the revelatory ‘Non più di fiore’,

however, we finally enjoyed Coote’s lovely full, burnished lower register,

as Vitellia is enlightened, recognising the error of her ways. We, too,

were ‘enlightened’, as the aria was sung with the house lights on - another

technical hitch, or designed to suggest spiritual illumination in contrast

to the prevailing moral darkness?

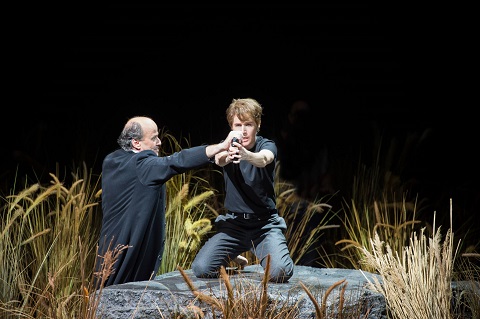

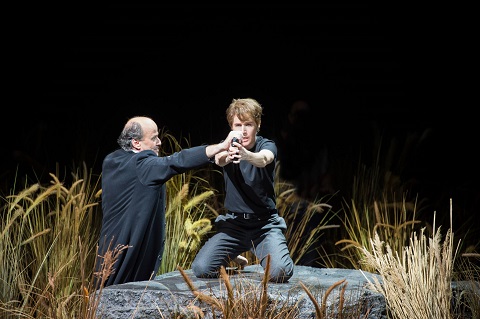

Tito (Richard Croft) and Sesto (Anna Stéphany). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Tito (Richard Croft) and Sesto (Anna Stéphany). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

American tenor Richard Croft, following the withdrawal of Steve Davislim,

was a benevolent patriarch, singing with soft-grained lyricism and fluency,

although he wasn’t entirely comfortable at the top and had a tendency to be

ponderous in the recitatives. This Tito was deeply tormented by the

dilemmas he faced, as his innate compassion clashed with the magisterial

demands of office, but he lacked a certain aristocracy - an imperial

nobility which is essential if the qualms caused by his high-mindedness are

to ring true. Tito is magnanimous, but he is not meek. Moreover, by placing

Tito’s quasi-infatuation with Sesto centre-stage, the production neglected

the political context for the drama: it was not clear why Tito must banish

Berenice - we see her depart bearing two suitcases - whom he loves but whom

his nation will not accept as Empress, nor why having initially chosen

Servilia as her replacement, she too is rejected in favour of Vitellia.

Servilia (Joélle Harvey). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Servilia (Joélle Harvey). Photo credit: Monika Rittershaus.

Joélle Harvey, who made a strong impression here in

La finta giardiniera

three year ago, sang with stylishness and delicacy as Servilia, giving

depth to the slight role and pleading for Sesto’s life with heart-moving

earnestness in her final aria. Annio, the role originally intended for

Stéphany, was beautifully sung by Canadian mezzo-soprano Michèle Losier who

captured all of Annio’s loyalty and honesty.

The playing of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment was tender and

spacious, though the ceremonial numbers might have had a little more

regality. Ticciati sensitively gave his singers the time they needed, but

there was occasional loss of momentum in the recitatives with too many longueurs and silences. Ashok Gupta (fortepiano) and Luise

Buchberger (cello), raised in the pit, were not once unsettled by the

hiatuses, however.

Some have seen La clemenza di Tito as a homage to Leopold II,

whose coronation as King of Bohemia the opera was commissioned to

celebrate; others, as a warning to pre-Revolutionary European rulers of the

dangers of the abuse of power. Certainly, contemporary political tensions

remind us of the need for leaders who will ensure the safety and security

of nations, as emphasised perhaps in the closing moments of this production

when Clive Bayley’s dark-voiced Publio - the unsettling, manipulative

commander of the Praetorian Guard - came out of the shadows to assume the

reins of power.

Another self-conscious directorial gesture, perhaps; but the superb cast

ensured that the sincerity which is at the heart of this opera was

preserved.

Claire Seymour

Mozart: La clemenza di Tito

Vitellia - Alice Coote, Sesto - Anna Stéphany, Annio - Michèle Losier,

Publio - Clive Bayley, Tito - Richard Croft, Servilia - Joélle Harvey,

Children - Rupert Wade and Logan Bradley; director - Claus Guth, conductor

- Robin Ticciati, designer - Christian Schmidt, lighting designer - Olaf

Winter, video designer - Arian Andiel, dramaturg - Ronny Dietrich, movement

director - Ramses Sigl, Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, Glyndebourne

Chorus (chorus master, Jeremy Bines).

Glyndebourne Festival Opera; Wednesday 26th July 2017.