It helps that the paintings are so much part of popular culture that

everyone recognizes his images of extreme excess. Bosch’s people wear

medieval dress, but their actions depict the subconscious, the ‘Id’

and existential guilt in operation, centuries before the concepts of psychology

found expression in formal language.

Like Carnina Burana,

Glanert’s Requiem is highly dramatic music theatre,

adapting the cataclysmic dreamscapes of Bosch’s paintings into music of

extremes as lurid as Bosch’s images.

Glanert’s Requiem unfolds in 18 episodes, rather like

panels in a medieval triptych. This gives the piece structure, making it easy

to follow. The teeming, sprawling panoramas Bosch depicts could plausibly be

depicted in sound, but that would probably be asking too much of most

audiences. Like Bosch, though, Glanert’s piece replicates extremes.

Literally heaven and hell, for the premise is the judgement Bosch faces after

death. Thus the standard elements of a Requiem Mass are interleaved with the

Seven Deadly Sins, the acrid flames of hellfire whipping against the smoke of

incense.

A harsh Voice (David Wilson-Johnson, narrating) calls from above

“Hieronymus Bosch!” Immediately we spring to attention. Bells

ring,. Throbbing, rushing figures in the choral line, suggesting the doomed

hordes we see in Bosch’s paintings. The orchestral lines veer wildly, lit

by screaming brass, the chorus screaming to crescendo. Suddenly the forces

fragment and, from the silence, a slow, low penitential intonation. An abstract

‘Requiem Aeternam’, the choral line flowing ambiguously, in almost

microtonal haze. like smoke. In ‘Gluttony’ the bass (the aptly

named Christof Fischesser) sings of food, his lines circular and rotund. The

text may be in Latin, but the meaning is clear. The choir responds with the

long, thin lines of an ‘Absolve Domine’, reinforced by

‘Wrath’ with tenor (Gerhard Siegel) and a ‘Dies Irae’

which ends with a vivid orchestral flourish. Another demon, ‘Envy’,

fights back. Soprano Aga Mikolaj’s fluid, curving lines mimic the lines

in the “heavenly” chorus— imitation is a sign of envy!

But the serene ‘Juste judex’ prevails. But where are we? The

organ solo (Leo van Doeselaar) lets rip with a frenzy that suggests a cathedral

organ hijacked by ‘Satan’. Despite the extremes of volume and

tempi, the lines between heaven and hell are, tellingly, blurred. In

‘Sloth’, the soprano sings langorously, joined in sensuous duet by

the mezzo (Ursula Hesse von den Steinen). ‘Pride’,

‘Lust’ and ‘Avarice’ appear, but the balance shifts

towards the big guns : Full choir, offstage choir, and orchestra in

increasingly full throttle : listen for the jazzy culmination of the

‘Domine Jesu Christe’. and the funky trumpet that heralds the

‘Agnus Dei’.

With the ‘Libera Me’ and ‘Peccatum’, we are in

Carmina Burana territory, bursting forth in a blaze, the earthly

chorus in raucuous flow, augmented by brass and percussion and the offstage

chorus singing of ‘lux perpetua’. Big forces. But is might right?

Glanert’s Requiem ends ‘In Paradisium’, here the

‘Voice from Above’ recites lines from the Book of

Revelation. Apocalyptic visions, marking the end of the world and of time.

Now, when the Voice screams “Hieronymus!”, he doesn’t add a

demonic epithet. With an unearthly low hum, the choir sings of the chorus

angelorum that brings eternal rest.

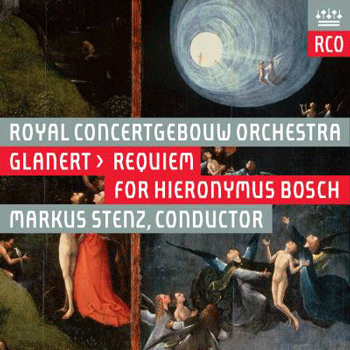

Glanert’s Requiem for Hieronymus Bosch was

commissioned to celebrate Bosch’s 500th anniversary, and premiered in

Sint Janskathedraal, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, in April 2016. So it’s a

public piece rather than a work of inward inspiration. It must be great fun to

perform, without being particularly demanding, technically or interpretively.

It could, in theory, be performed elsewhere, much as Carmina

Burana is, these days. It is admirably performed on this world

premiere recording made in November 2016 with the top-notch Royal Concertgebouw

Orchestra Amsterdam, conducted by Markus Stenz.

Glanert was one of Hans Werner Henze’s few disciples. Henze’s

political beliefs influenced his music, though he never sacrificed high

artistic and intellectual standards. Glanert is a man of the theatre, too, with

a more earthy sense of humour than Henze had, though that quirkiness

isn’t too obvious. When the ENO did Glanert’s

opera Caligula, London audiences just couldn’t get it.

(Please read HERE what

I wrote about Caligula, which I first heard in Frankfurt). In

this Bosch Requiem, Glanert again mixes grotesque with irony.

Just as the vastness of Carmina Burana appealed to Nazi

taste, the vastness of this Requiem veers on parody. Will it

be loved for its vulgarity or its irony? Just as the paintings of Hieronymus

Bosch reveal the viewer, Glanert’s Requiem reveals the

listener.

Anne Ozorio