23 Aug 2017

Glimmerglass: Well-Realized Rarity

It is hard to believe that an opera by Donizetti is receiving its American premiere at the 2017 Glimmerglass Festival, but such is the case with The Siege of Calais.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

It is hard to believe that an opera by Donizetti is receiving its American premiere at the 2017 Glimmerglass Festival, but such is the case with The Siege of Calais.

It is a welcome discovery, chock-full of soaring melodies and surging phrases that recount the moving tale of the six burghers of Calais willing to sacrifice their lives in order to save the city and citizens they love from isolation and destruction. Rodin immortalized the burghers in his famous sculpture, of course, but Donizetti and his librettist Cammarano have also crafted a compelling work of art that is no less impressive. Perhaps its neglect is owing to the extreme interpretive demands on its trio of principal soloists, and here the company outdid itself, peopling its cast with thrilling vocalists.

Soprano Leah Crocetto stars as Eleonora, devoted wife to Aurelio, the mayor’s son missing in the swirling military action. Ms. Crocetto announced herself as a major talent in Rossini’s Maometto II at Santa Fe just a few short years ago. Since then, she has taken on Puccini and Verdi to ever-growing acclaim. With Eleonora, she returns to bel canto with riveting results.

Leah Crocetto as Eleanora and Aleks Romano as Aurelio

Leah Crocetto as Eleanora and Aleks Romano as Aurelio

Not only can she sing accurate and meaningful coloratura with utmost ease, but she also has an expressive range that effectively spans from hushed whisper to raging fury and all points in between. Her generous, creamy spinto has an uncommonly fine luster and appeal, and it is wedded to a simple, sincere acting style, evoking the gifts of the great Caballe. Based on this outing, Leah Crocetto seems poised to be a major international star.

While she may be the recognizable “name” of the cast, the leading role is the activist son Aurelio, and mezzo Aleks Romano matched Crocetto note for note in virtuosity and tonal allure. First, I have never seen a woman in a trouser role look so believably manly. The petite singer is as convincing in her gender-bending as Hilary Swank in her Oscar winning turn as Brandon Teena (Boys Don’t Cry).

Ms. Romano has a searing vocal delivery, her exciting, focused tone appealingly colored by a somewhat urgent vibrato. When Aurelio is riled up (which is often), she hurls inflammatory declamations that ring thrillingly throughout the house. But when she shares loving, concerned duets with Eleonora, Aleks can hone her secure tone to a tender filigree of sound that is heart stopping in its emotional effect. There are two duets in which these two remarkable vocalists sing melting phrases in thirds that are not meant merely for human ears. As their inimitable instruments tumble over each and urge each other to ever greater emotional engagement, well, this is as good as it gets.

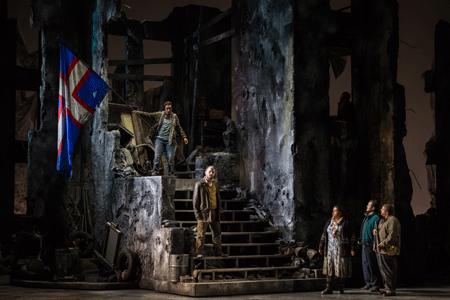

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III

The role of mayor Eustachio de Sainte-Pierre is exceedingly well served by the imposing bass baritone, Adrian Timpau. His dark, pointed instrument served notice that a major talent has arrived on the scene. Mr. Timpau exuded vocal authority and stylistic acumen, and he mastered every trial of this difficult, lengthy assignment. Mr. Timpau joins the Met’s Lindeman program next year, and his future stardom seems all but assured. Chaz’men Williams-Ali’s ringing, plangent tenor brought much joy to the proceedings as Giovanni de Aire. His sound contributions to the extended ensembles were noteworthy.

Andres Moreno Garcia has a very pleasant, rolling baritone that made much of his brief stage time as Edmondo. Michael Hewett, a memorable Jud (Oklahoma!) the night before, successfully impersonated King Edoardo III. Mr. Hewett has a burnished baritone, which easily served up fine Donizettian style. On this occasion, his very upper register didn’t always turn over to match the ease of his upper-middle. Helena Brown’s imperious, generous soprano made a major impact as Queen Isabella. Talented young bass Zachary Owen was dramatically vested in the cameo of the English Spy, but his potent delivery sometimes pressed to veer off pitch. Joseph Leppek (Giacomo de Wisants), Carl DuPont (Armando), and Rocky Lasky (Filippo) all made solid efforts with their focused, steadfast performances.

In the pit, Joseph Colaneri whipped up a rousing interpretation of this rarity that found his orchestra responding with a vigorously theatrical, stylistically rich reading. Under Maestro Colaneri’s knowing baton, the band was a collaborative partner in the engrossing story, pairing flawlessly with the soloists and urging David Moody’s well-tutored chorus (excellent diction!) to great heights. While the entire orchestra was rightly cheered to the rafters, I have to single out the extended clarinet solo introduction to one of the major set pieces that was a thing of luminous beauty.

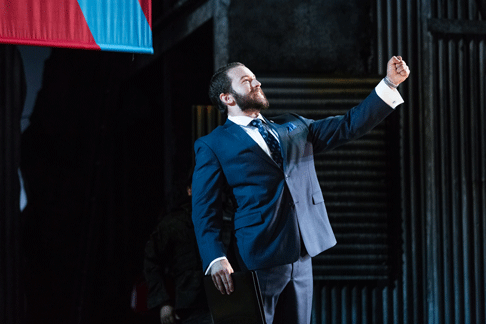

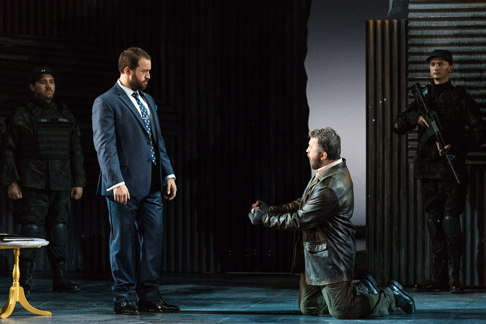

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III and Adrian Timpau as Eustachio de Saint-Pierre

Michael Hewitt as Edoardo III and Adrian Timpau as Eustachio de Saint-Pierre

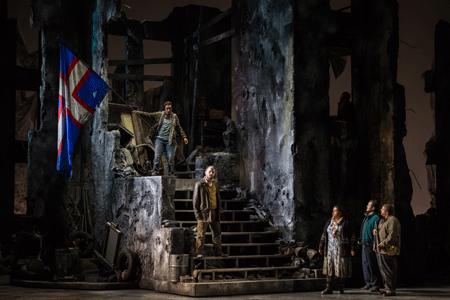

So what does this piece have to say to us in today’s context? If you are director Francesca Zambello, the answer is “plenty.” She has found great resonance in raising the plight of refugees struggling in modern day Calais, and grounding it in the ruined setting of a war torn near eastern town. The first image of James Noone’s evocative set design is seen as we take our seats: a high corrugated, jagged, barbed wire laced sheet metal barrier with “Calais” boldly graffitied onto it serves as an act curtain. A bombed out car lies in state down left.

Ms. Zambello sets her concept up effectively with a staged overture. First, soldiers patrol the fence. When the coast is clear, a desperate intruder clambers over the wall to steal food from the soldiers’ unattended knapsacks. After he is discovered and narrowly escapes, the soldiers regroup across the apron in time to sing the ringing opening chorus. The wall parts and recedes off left and right, revealing the bombed out shell of a three story building that is all too depressingly familiar a visual from the evening news.

Mr. Noone’s hulking set includes a large staircase that the director skillfully uses to create meaningful levels and stage pictures. The turntable is put to good use as it spins the structure to suggest different locales. Costume designer Jessica Jahn’s carefully selected, character specific street wear for the downtrodden, and tailored uniforms and business wear for the privileged were aptly inspired by today’s front page photos. Mark McCullough’s austere lighting design was calculated to highlight important dramatic moments, balancing well-selected specials with murky shadow effects. This was a most convincing feat of story telling, making a potent case for a forgotten 19th century opera by making it all too relevant in today’s world. By making the character relationships so intensely believable and their predicament so universally human, Francesca has even managed to gloss over the pretty big flaw in the denouement.

Edoardo has adamantly refused over and over to spare the burghers’ lives and indeed, soldiers point assault rifles menacingly at the intended targets throughout the extended penultimate ensemble. Queen Isabella has pleaded with husband Edoardo to spare them, but he unceremoniously rejects her. Musically, dramatically, the piece churns inexorably to certain tragedy. Then, in the briefest of moments that is the operatic equivalent of “honey, c’mon now. . .” Isabella gets Edoardo to say the shrugging equivalent of “Oh. . .okay.” And, basta, everyone is free. Never you mind. This talented group has such total commitment to the piece, and they believe in it so strongly, that damn if we don’t suspend our disbelief as well.

There is such a wealth of musical riches in The Siege of Calais (at least with this consummate team) that it is astonishing it has take so long to resurface. Now that the enterprising Glimmerglass Festival has emphatically demonstrated there are singers capable of handling it, and proven there are audiences ready to be thrilled by it, maybe it will find the widespread recognition it deserves.

James Sohre

Cast and production information:

Eustachio de Sainte-Pierre: Adrian Timpau; Eleonora: Leah Crocetto; Giovanni de Aire: Chaz’men Williams-Ali; Pietro de Wisants: Makoto Winkler: Aurelio: Aleks Romano; English Spy: Zachary Owen; Giacomo de Wisants: Joseph Leppek; Armando: Carl DuPont; Edmondo: Andres Moreno Garcia; Edoardo III: Harry Greenleaf; Isabella: Helena Brown; Filippo: Rocky Lasky; Conductor: Joseph Colaneri; Director: Francesca Zambello; Set Design: James Noone; Costume Design: Jessica Jahn; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough; Hair and Make-up Design: J. Jared Janas, Dave Bova; Chorus Master: David Moody