The first Act took a little time to settle. Alexander Joel led the ROH

Orchestra through a pretty work-a-day reading of the overture in which some

unfocused intonation seemed visually symbolised by the precariousness of

Sofia Formia’s vulnerable Gilda, perched high on an extending platform,

peering tragically into the gloom.

The ball scene was less divertissement than downright debauchery. McVicar

leaves us in no doubt of the nature of Rigoletto’s role at the Duke’s

licentious court: he provides ‘entertainment’ in the form of facilitating

violent seduction and rape, and the assault on Monterone’s daughter -

accompanied by hedonist whoops of the fornicating couples and avid voyeurs,

and a vicious prod from Rigoletto’s staff - is played out for all to see.

There’s no sense of a ‘dance’, though there’s plenty of movement, wild and

ugly, as well as much intrusive noise, including the thump of Rigoletto’s

crutches as they stab at the floor. Vale’s leaning, metallic wall - which

swivels to reveal Rigoletto’s tumble-down shack - is a steely silver, an

apt emblem of the emotional coldness and cruelty of this Renaissance den of

iniquity, though Tanya McCallin’s costumes add some welcome colour.

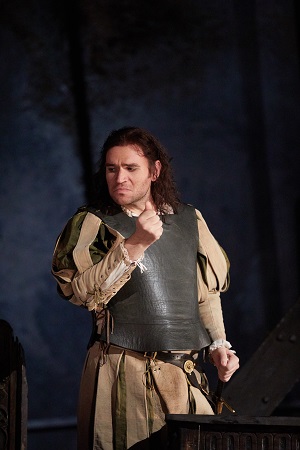

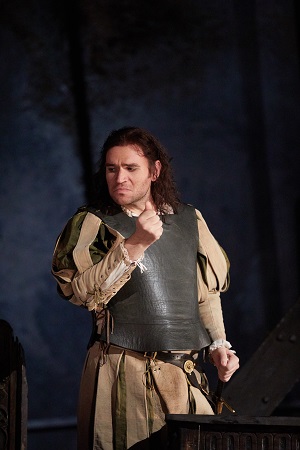

Michael Fabiano (Duke of Mantua). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Michael Fabiano (Duke of Mantua). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

The sense that things might escalate out of control was exacerbated by

disagreements about tempo between stage and pit, which created musical

disequilibrium to match the dissolution of morals. Into this maelstrom,

Michael Fabiano flung a roaring ‘Questa o quella’: there was no doubt of

this Duke’s power and presence. But, the physical and vocal swagger which

characterised Fabiano’s account became ever more coarse, loudness replacing

legato: this Mantuan libertine was certainly a dissolute pleasure-seeker

but there was little sensuality in Fabiano’s singing. There was a tendency

to shout rather than seduce in ‘È il sol dell'anima’ and Fabiano seemed to

make no attempt to imbue ‘Parmi veder le lagrime’ with aristocratic

elegance; his Duke was a thug and his supposed sorrow merely superficial. I

became increasingly puzzled by this interpretation as the performance

proceeded.

Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Dmitri Platanias’s leather-clad, crutch-wielding hunchback lumbered and

lurched like an aggressive stag-beetle, his crooked jester’s cap-and-bells

jiggling grotesquely. Platanias baritone was hardened with anger, swelling

with barely repressed rage. Platanias released this fury with fire in

‘Cortigiani, vil razza dannata’ when Gilda is abducted by the Duke’s

courtiers; but, he seemed emotionally disengaged during the father-daughter

duets, absorbed by his own suffering rather than consumed with obsessive

paternal protectiveness. This Rigoletto seemed to take no responsibility

for the tragedy which ensues, and thus garnered little sympathy.

Sofia Fomina (Gilda) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Sofia Fomina (Gilda) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Sofia Fomina has a big soprano and the top notes were powerfully projected,

though a wide vibrato, particularly lower in the range, often caused the

focus of the note to spread. However, dramatically the Russian soprano also

seemed a little detached at times - I wasn’t convinced that this Gilda was

intensely attracted to the Duke, overcome by unconscious, unfamiliar sexual

desire - although Fomina’s commitment in the final scene was unstinting.

Andrea Mastroni was a fantastic Sparafucile, a man of the shadows, his evil

understated but undoubtable: Mastroni’s sensitive, graded parlando

in Act 1 told us all we needed to know. Nadia Krasteva’s richly coloured

mezzo-soprano conveyed Maddalena’s voluptuousness and the Bulgarian singer

acted persuasively. Several Jette Parker Young Artists acquitted themselves

well - Francesca Chiejijna (Countess Ceprano), Dominic Sedgwick (Marullo)

and Simon Shibambu (Count Ceprano). Despite his suit of armour, James

Rutherford’s Monterone was disappointingly underpowered, his curse

overshadowed by the general cacophony and depravity.

Andrea Mastroni (Sparafucile) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

Andrea Mastroni (Sparafucile) and Dmitri Platanias (Rigoletto). Photo credit: Mark Douet.

When my colleague, Anne Ozorio, reviewed the

2012 revival

of this production she admired the way McVicar ‘gets to the visceral

drama’. I wouldn’t disagree with that … but, on this occasion, the

bleakness that she notes was unremitting, as neither cast nor orchestra

summoned the genuine, if fleeting, tenderness that tempers the machismo and

malevolence.

This first performance in the run was dedicated to the memory of

Russian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky.

Claire Seymour

Verdi: Rigoletto

Duke of Mantua - Michael Fabiano, Rigoletto - Dimitri Platanias, Gilda -

Sofia Fomina, Sparafucile - Andrea Mastroni - Maddalena - Nadia Krasteva,

Giovanna - Sarah Pring, Count Monterone - James Rutherford, Marullo -

Dominic Sedgwick, Matteo Borsa - Luis Gomes, Count Ceprano - Simon

Shibambu, Countess Ceprano - Francesca Chiejina, Giovanna - Sarah Pring,

Page - Louise Armit, Court Usher - Olle Zetterström; Director - David

McVicar, Conductor - Alexander Joel, Set designer - Michael Vale, Costume

designer - Tanya McCallin, Lighting designer - Paule Constable, Movement

director - Leah Hausman, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, London; Thursday 14th December

2017.