29 Jan 2018

William Tell in Palermo

This was the infamous production that was booed to extinction at Covent Garden. Palermo’s Teatro Massimo now owns the production.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

This was the infamous production that was booed to extinction at Covent Garden. Palermo’s Teatro Massimo now owns the production.

The Palermitani, evidently less offended by abject sexual violence, tolerated the production’s humiliation and rape of a young woman without remark (having tacitly accepted as well Hunding’s gang rape of Sieglinde in last year’s Ring). Not that Damiano Micheletto’s William Tell production was not resolutely booed at this opening night of the Teatro Massimo’s one-hundred-twenty-first season. It was indeed.

It was a relaxed, festive evening at the Teatro Massimo, a red carpet runner ushering the very well-dressed audience past two magnificently uniformed guards at the entrance, shining swords at their sides. Never mind the heavy police presence in the piazza in anticipation of a demonstration (unrealized) against such extravagance.

At the hour the performance was to begin an announcement was made delaying the beginning by one-half hour due to a strike of some sort. No one minded as it was a very social evening, the animated conversations would have been hard to interrupt anyway.

Guillaume Tell, Rossini’s French style grand opera can be a very long evening (five hours plus in a recent Rossini Opera Festival production). In Palermo just now it was reduced to a bit over four hours, the act one marriage ballets were sacrificed, plus other less prominent sections.

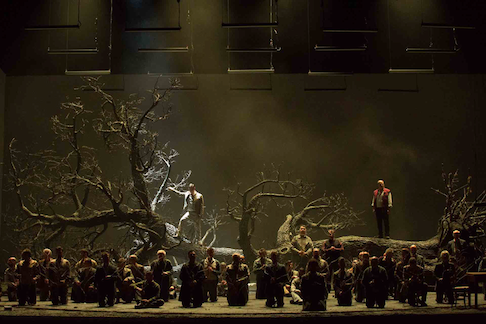

Dmitry Korchak as Arnold (in white light), Roberto Frontali as William Tell (in red vest)

Dmitry Korchak as Arnold (in white light), Roberto Frontali as William Tell (in red vest)

The Michieletto production reduced Rossini’s spectacle to bare bones — an illustrated comic book story (projected from time to time) was its cornice from which a surrogate William Tell emerged to cement William Tell’s patriotic resolve at crucial moments. Rossini’s quite specifically human, and complicated storytelling was transformed in Palermo into a ceremonial hymn to liberty, told in three bold strokes, Gesler’s thugs tore out the tree of peasant life (Gesler is the tyrant villain). The tree lay dead on the stage until William Tell eradicated Gesler. A new tree was planted as the Swiss peasants celebrated their emancipation from tyranny.

The effect of the production, and it was considerable, was exponentially increased by the expansive conducting of Teatro Massimo’s music director Gabriele Ferro. His tempos were indeed deliberate, elaborating the ceremonial tone of the production, the flights of lyricism were reduced to the beautiful sounds of the overture’s flute solo and to the splendidly voiced fisherman’s song that opens the first act.

After this it was all business. The chorus of Swiss peasants was grimly seated at regimented tables to grimly celebrate love, marriage and the harvest. William Tell got right to work liberating them through his heroic resolve, abetted by the heroic courage of his son Jemmy and the stoicism of his wife Hedwige. The murdered Melcthal’s son Arnold came to his senses and swore to avenge his father (though William Tell actually did all the work), not without the help of the Hapsburg princess Mathilda whom he loved.

Done.

The chorus and the principals then let Rossini’s final hymn to liberty soar, and it was spine tingling. The gigantic dead tree magically lifted (grand opera is famous for spectacular scenic effects, and this was just that) to allow a young boy to pass under with a sapling that he planted down stage center.

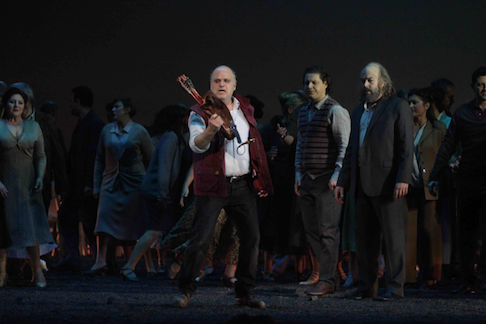

Roberto Frontali as William Tell

Roberto Frontali as William Tell

The Micheletto production was given vibrant life by an excellent cast whose voices and personae seconded its conceptual intentions. Baritone Roberto Frontali (San Francisco Opera’s recent Scarpia and L.A. Opera’s recent Falstaff) brought sharp edge to William Tell, no longer Rossini’s father figure he was far more a warrior. Soprano Anna Maria Sarra as William Tell’s son Jemmy was not diminutive, rather she was full-sized both vocally and morally, a warrior who mimed a child's movement.

Arnold, rendered impotent by love was sung by Russian tenor Dmitry Korchak in fine French and fine Rossini style. He was in love with Mathilde, the Hapsburg princess sung by Tbilisi (Georgia) born Nino Machaidze, a soprano of ample voice and great charm who negotiated her bit of fioritura with ease and to good effect.

William Tell’s stolid friend Walter Furst, sung by bass Marco Spotti, remained in the shadows, helping when called upon. Albanian mezzo Enkelejda Shkoza made Tell’s wife Hedwige a strong, purposeful presence supporting her husband and son, and a strong, purposeful voice in the upper registers of Rossini’s large ensembles, in Palermo executed with requisite magnificence.

The villain Gesler was delivered in high caricature by bass Luca Tittoto, underscoring the Italianate nature of this French evening (after all we were in Palermo!). Tenor Matteo Mezzaro, Gesler’s lieutenant Rodolphe, managed infectious charm in his nefarious duties.

The splendid first act’s fisherman’s song was sung by Sicilian tenor Enea Scala for the opening night performance only. He will sing Arnold in the final two of this eight performance run — the dynamic will be greatly changed. As the fisherman he and Enkelejda Shkoza were the only carryovers from the Covent Garden cast.

The orchestra and chorus of the Teatro Massimo seccured the solid artistic level of the evening, proving again that this Palermo theater is among the finest in Italy.

Michael Milenski

Cast and production information:

Guillaume Tell: Roberto Frontali; Arnold: Dmitry Korchak; Walter Furst: Marco Spotti; Melcthal: Emanuele Cordaro; Jemmy: Anna Maria Sarra; Gesler: Luca Tittoto; Rodolphe: Matteo Mezzaro; Ruodi: Enea Scala; Leuthold: Paolo Orecchia; Mathilde: Nino Machaidze; Hedwige: Enkelejda Shkoza; Un chasseur: Cosimo Diano. Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Massimo. Conductor: Gabriele Ferro; Metteur en scène: Damiano Michieletto; Scene designer: Paolo Fantin; Costumes: Carla Teti; Lighting: Alessandro Carletti. Teatro Massimo, Palermo, January 23, 2018.