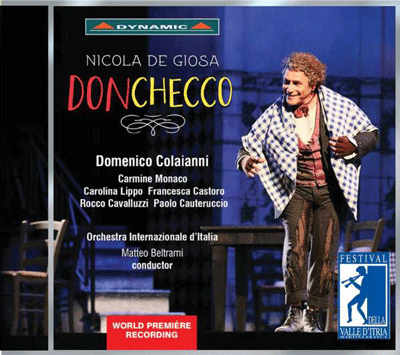

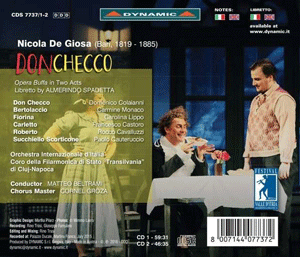

But I am glad I was sent this world-premiere recording of what was, in his lifetime and beyond, his best-known work, a comic opera from 1850, in which the title role (and only that role) is in Neapolitan dialect. De Giosa was a student of Donizetti, and Don Checco shows that he learned great things from his teacher and added touches of his own.

The recording was made in July 2015, during one or more performances at the Valle d’Itria Festival in Martina Franca (an important town, close to Bari but located inland). The Festival presents several forgotten operas every summer. Its head is Fabio Luisi, well known to Americans during his years as principal conductor of the Met (beginning in 2011). Recent and upcoming works have included rarely performed operas by Handel, Vivaldi, Piccinni, Meyerbeer, and Vaccaj (the latter’s Giulietto e Romeo). Shorter and smaller-scale works (e.g., Puccini’s Gianni Schicchi and Monteverdi’s Il ballo dell’ingrate) are performed in the cloisters of the nearby eighteenth-century church of San Domenico.

The life of Nicola De Giosa is nicely summarized in the informative booklet-essay by musicologist Dinko Fabris. The English translation of the essay is comprehensible, if not always idiomatic. The plot summary given in the booklet is likewise very helpful. I easily downloaded the libretto and translation from dynamic.org and found that these helped me a lot, especially in extended passages of spoken dialogue. Again, the translation (uncredited) is sometimes misleading: Don Checco does not enter “very poorly dressed” (which might suggest an outfit inappropriate to the occasion); rather his clothes are those of someone who is utterly impoverished (meschinissimo)—that is, his outfit is in tatters. The track list in the booklet is also misleading because it often mentions only the first character who happens to sing.

I said that there are extensive passages of spoken dialogue. This was true of all operas written for the Teatro Nuovo in Naples. (Operas composed for other houses had their recitatives turned into speech when performed at the Nuovo; and vice versa: Don Checco was done with recitatives when performed elsewhere in Italy.) The use of spoken scenes between the sung numbers brings Don Checco close in spirit to French opéra-comique, Viennese operetta, and Gilbert and Sullivan (and thus to their offspring, the Broadway musical). For another example of Italian opera with spoken dialogue, I heartily recommend Adelson e Salvini (1824), a surprisingly strong opera written by the 23-year-old Vincenzo Bellini, during his graduation year at the conservatory in, yes, Naples. (A first-rate new recording of Adelson e Salvini—with major singers, including the tenor Enea Scala—is the first to make use of the forthcoming critical edition. It is reviewed here at Opera Today by Claire Seymour and, at the Boston Musical Intelligencer, by myself.)

The libretto from Dynamic states that the singer of the title role has improvised some of his dialogue. I suspect that he is not the only one adding lines. For example, the innkeeper Bartolaccio (a nickname, something like Big Fat Bartholomew) vents his annoyance in spoken exclamations over the orchestral postlude to Act 1, scene 2, as the chorus of male villagers leaves his inn. This helps smooth the transition to the beginning of scene 3. Even more amusing: on two occasions a musical number is interrupted (in the middle of a cadential phrase!) by a bit of what seems to be invented spoken dialogue; then the singing and orchestral playing resume, to bring the number to a close.

De Giosa’s music is a constant delight. After a five-minute stretch of rapid-fire spoken exchanges, the re-entry of orchestra and singing always feels like a welcome moment for emotional expansion. Often the dramatic impetus that has been set up in speech continues into the next musical number, thanks to the skillful (and witty) libretto and to De Giosa’s skillful ways of contrasting the reactions of the different characters.

The orchestration is finely crafted. I particularly enjoyed the music for the bassoon and shivering strings when Don Checco first enters and declares: “I’m freezing to death!” My ears also perked up at a few points when the composer creates back-and-forths between the winds and strings (e.g., at the end of Don Checco’s introduction to his final song). The highlight of the second act is a duet in which the two bassi buffi (Don Checco and the innkeeper) vie to outdo each other in rapid patter, against an enchanting dancelike tune in the orchestra. The effect is all the more amusing because their patter involves comical leaps of an octave. One can see how De Giosa’s good ear for vocal effects and instrumental colors helped him get chosen to conduct in prominent opera houses—not just in Italy but also in Cairo (at the theater where Aida received its world premiere) and Buenos Aires.

The singers, all Italian and all previously unknown to me, have firm, focused voices—nary a wobble to be heard here. (Except at times from Bartolaccio, the grumpy innkeeper, but a somewhat worn voice seems appropriate for a character who is a bit old.) All enunciate the humorous text clearly and with appropriate variety. The extensive spoken dialogues gave me great occasion to be thankful that the singers are native Italian-speakers. The interchanges flow swiftly and naturally, and I was able to recognize many words and phrases by ear alone. A few spoken lines have been updated to the era of the costumes (see below): there are pointedly humorous references to Chanel cologne and to film-actress Gina Lollobrigida, and one new bit is directed to the opera’s conductor! (The libretto reproduces and translates the words that we hear sung and spoken; the listener is nowhere informed that updatings have been made.)

The audience members, to judge by their laughter, clearly loved Domenico Colaianni, who gives Don Checco not just a heavy Neapolitan accent but also a shifting variety of moods: hangdog, wheedling, fake-pompous, and so on. Still, since I was not able to fully appreciate the nuances of his character’s Neapolitan dialect, I responded more to the young lovers. Carolina Lippo sings the pert and savvy Fiorina (the innkeeper’s daughter) with effortless command. Francesco Castoro, as her timid young lover (a waiter in her father’s inn), has a voice that, when he is singing alone, is often beautiful and with wonderful “ping” but, in an ensemble, tends to sound tight and devoid of specific character.

I imagine that the ducal-palace courtyard seats hundreds of listeners, rather than the thousands in many modern opera houses. This would explain how the singers are able to make their points without ever having to force their voices. I have been told that the palazzo courtyard is unroofed. Honors to the engineers for having nonetheless captured the sound so vividly!

The festival orchestra—mostly Italians—is decent-sized, sonorous, and totally effective. The score calls for the normal Italian comic-opera orchestra of the time (including pairs of clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets, and trombones, plus a cimbasso, whose part is presumably played here on the tuba). The passages for the chorus of villagers (men only) are superbly sung, with good sense of involvement in the action, by a group from Romania.

Conductor Beltrami keeps things moving, even in more lyrical numbers. He contributes some elegant orchestral phrasing: for example, tapering a series of repeated chords, instead of hammering them all at the same or, worse, increasing volume.

Indeed, the sonics of this recording are better than those on some recordings, of equally recent vintage, that were made in a radio studio or empty concert hall. (See my complaints, in reviews on this site, about Karine Deshayes’s recital of Rossini arias and songs and soprano Emalie Savoy’s debut CD.) The sound can get a bit congested at moments when everyone on stage is singing out, but any such problems pass quickly.

An appreciative review of this same Martina Franca staging of Don Checco (but a year earlier, 2014, and with different singers and conductor) can be found at Bachtrack.com. It contains two photos of scenes from the production that helpfully complement those in the CD booklet. As the various photos show, the sets and costumes were updated to the mid-twentieth century, but they otherwise represented precisely what the libretto specifies: “a village inn not far from Naples.” There were no so-called imaginative or postmodern directorial touches to get in the way here, such as moving the opera to an impoverished favela in the hills above modern-day Rio de Janeiro, or to a penal colony on the moon after a nuclear apocalypse.

On YouTube, two of Don Checco’s arias can be heard, performed in a different city (De Giosa’s hometown, Bari, 2013) by a different baritone (the one who sings the innkeeper on the CD set). YouTube also has a video excerpt of the song with which Don Checco closes the opera (from the Martina Franca production, but sung by yet a third baritone: Bruno Taddia).

Since a conductor-musicologist (Lorenzo Fico) went to the bother of preparing an edition of the score for these various revival performances (Bari and Martina Franca), it would be wonderful if some publisher would make that edition available in print, enabling us to savor the full extent of De Giosa’s artistry. And, while I’m placing my order, why not also a piano-vocal reduction to facilitate staged performances and to enable arias and duets to be done in voice recitals? I would suggest that the publisher include, as an alternative, recitatives (preferably historical or, if those do not exist, newly composed), to make life easier for singers who cannot speak dialogue convincingly in Italian and Neapolitan. Much of the work’s charm and local flavor would still survive through such a transmutation.

De Giosa composed fifteen or more other operas, several of them serious. Are any of them as effective as Don Checco? I hope some Italian theater or summer festival tries to find out, and that Dynamic records the result as neatly and capably as they have done here.

If you have access to the Naxos Music Library—say, by subscribing on your own or through a public or university library that subscribes—you can listen to this recording. You can also download the libretto there for free, by clicking on the word Booklet. Oddly, the actual CD booklet, with Fabris’s enormously helpful essay, is not available online.

All in all, this comic opera and its spiffy recording offer much unexpected pleasure, as well as food for thought about what features made a work successful in its own time and place and what features (and alterations) might enable it to communicate across the centuries and across cultural and linguistic barriers.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book.