‘We lived in a heap together in one barrack. The flooring was rotten and an

inch deep in filth, so that we slipped and fell. When wood was put into the

stove no heat came out, only a terrible smell that lasted through the

winter.’ So wrote Dostoevsky, in a letter to his brother, about his

experiences in the Siberian prison camp at Omsk where he was incarcerated

between 1850-54, because of his association with a group of political

dissidents who had tried to assassinate the Tsar. It was the

quasi-fictionalised account of Dostoevsky’s imprisonment, published

predominantly in the journal Vremya between 1860-62, that was

Janáček’s source for the libretto of From the House of the Dead.

The composer selected characters and incidents - events that occurred in

the prison hospital, the celebration of feast days - and assembled them

into a mosaic punctuated by three extended narratives in which individuals

recount the violent crimes and contexts that have resulted in their

incarceration and suffering.

Warlikowski tells us that he ‘made a conscious decision not to re-read

Dostoevsky’s novel’ wanting to keep at bay his youthful fascination with

this text, and ‘focus more directly on Janáček’s adaptation of the novel,

and use his score and libretto to create a world not specifically

‘Russian’, but more universal in feel.’

Nothing wrong with that: violence, (in)justice and freedom are universal

concerns, and all human existence involves suffering in some form. But, the

practical outcome might lead one to think that the opera had been based

upon a text which read, ‘We lived together in a shabby recreation hall,

playing basketball, lounging about in smart tracksuits, watching football

on a plasma television screen. A prostitute was made readily available, and

on public holidays we were treated to champagne and soft-porn

entertainment.’ Warlikowski titles his programme article ‘A Journey into

Hell’ but in fact these detainees seem to be having quite an indulgent - if

not very salubrious - time.

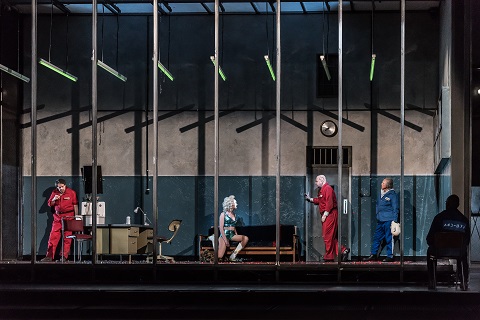

Warlikowski and his designer Małgorzata Szczęśniak have replaced

Dostoevsky’s Siberian gulag with a modern penitentiary. The open stage is

vast and bare. Stage right is a glass office where the Prison Commander

reads a newspaper, occasionally looking up to check the cctv surveillance

monitor, as prisoners wander in and out to do business with the

drug-dealing guards. The office swivels and, from my position in the

Balcony, the glass frequently reflected conductor Mark Wigglesworth in the

pit, weakening the realism, physical and psychological, that Janáček’s

music so powerfully establishes.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Photo credit: Clive Barda.

During the overture it becomes clear that when Warlikowski says he wants to

make the opera ‘more universal’ what he actually means is more

‘ideological’. Projected onto the steel squares which form a bulwark of a

stage curtain, a film of Michel Foucault critiquing the prison system

unfolds. If the French philosopher’s words have power they don’t really

have relevance here - Janáček and Dostoevsky were more interested in man’s

potential if not for forgiveness then at least for understanding, than in

the notion that the justice system only exists to justify the existence of

the police.

Moreover, the video images distract from what we are hearing - an

objective representation of social reality: that is, the clinking chains,

whiplash sounds and screams, mechanical sounds and the drum rolls which

break up the day as the opera proceeds. And, this is the principal problem

with Warlikowski’s production: it doesn’t listen to what the music is

saying and doesn’t respect the balance between realism and escapism that

the score achieves, as Janáček’s bitter extremes of harmony, orchestration

and tessitura suddenly surge with a lyrical beauty so intense that it is

almost painful.

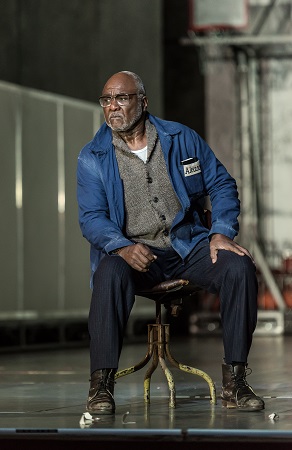

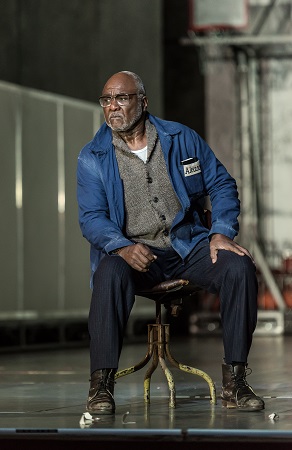

Willard W. White as Alexandr Petrovič Gorjančikov. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Willard W. White as Alexandr Petrovič Gorjančikov. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Time after time I found myself distracted by the frenetic stage activity -

such as the hyper-manic break-dancing of four black dancer-prisoners -

which obscured significant events and overpowered the libretto’s moments of

narrative focus and stillness. The arrival and humiliation of Petrovič at the start of Act 1, and his subsequent flogging, for example, almost passed me by, and this

was not because Willard White was anything less than superb as he tried to

maintain the ‘aristocratic’ prisoner’s human dignity. The prisoners may be

indifferent to the beating Petrovič receives, as he stands for their own

sufferings; but we are not, and it matters that his abusive treatment is

pushed by Warlikowski to the margins, not least because the beating mirrors

the violence in the tale which Luka is narrating - thus merging prison life

with the world outside, as direct and reported intersect.

Pascal Charbonneau as Aljeja. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Pascal Charbonneau as Aljeja. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Moreover, Petrovič is central to the opera’s shifting energies: at the

close, his freedom is emblematic, bound with both the release of the eagle

that has been cruelly baited by the prisoners and with the sadness of

separation felt by Aljeja, who is losing a friend - but also indicative of

renewal.

But, Warlikowski is not much interested in such renewal, or in the eagle,

though the latter’s instinct for freedom is associated with Dostoevsky’s

definition of the psychological motive behind crime as a burst of free

will, thus blending freedom and captivity in a single motif. Here, ‘The

Eagle’ is the name of a black basketball player who may or may not lob the

ball through the hoop in the final moments of the opera.

This opera is not concerned with philosophical speculations about justice

and the police force but with human motivations, acts and humanity’s desire

for freedom - as expressed in the three main solo narrations. One could not

fault the performances of Štefan Margita as Luka Kuzmič or Ladislav Elgr as

Skuratov. But, the energy with which their strong, unflinching tales of

violence begetting violence should surge was blunted by the onstage

busyness, and in Skuratov’s case by another pre-Act projection, this time

of the real-life reflections of a prisoner on death row: truly distressing

but, in this context, also diverting. For Skuratov’s narration should hint

at the outside world, the freedom of the limitless steppes, releasing the

tension and admitting romance and heterosexual love into the prison as it

is listened to by the fascinated prisoners. And, Warlikowski once again

added unnecessary action - in this case, a mime by Pascal Charbonneau’s

Aljeja, to the tale.

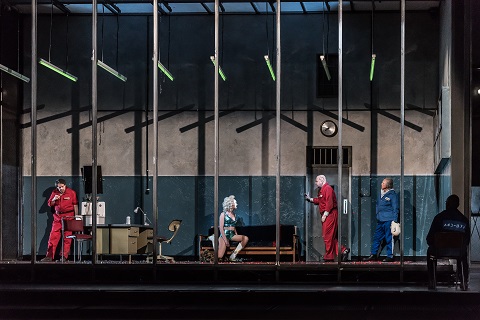

Štefan Margita as Luka Kuzmič, Allison Cook as Prostitute, Johan Reuter as Šiškov, Alexander Kravets as Čerevin. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Štefan Margita as Luka Kuzmič, Allison Cook as Prostitute, Johan Reuter as Šiškov, Alexander Kravets as Čerevin. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Similarly, the festive atmosphere of the following Easter celebrations

further heightens the emotion and evokes freedom. Warlikowski took the

ironic parallels which the festive entertainments offer to the tragic drama

of sexual love to extremes, however, as the men resorted to battering and

abusing inflatable dolls in a soft-porn extravaganza fuelled by champagne.

Johan Reuter as Šiškov. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

Johan Reuter as Šiškov. Photo credit: Clive Barda.

We had to wait until Act 3 for the feverish intensity to find a focus, in

Šiškov’s terrible narrative about the tragic mistreatment of Akulka. Wanton

and worthless, despised by his fellow prisoner he may be, but Johan

Reuter’s warm and commanding delivery made Šiškov’s narrative utterly

compelling, as the orchestral music, punctuated by the moans of pain of the

patients in the hospital prison, invited our sympathy. But, even here,

Warlikowski could not quite trust the score, and Allison Cook’s Prostitute

was called upon to mime the narrative - yet another needless intrusion.

The entire cast sang and acted with captivating conviction: the sufferings

and sorrows, flaws and failings of Nicky Spence’s Nikita, Grant Doyle’s

Čekunov, Graham Clark’s Antonič, and the prisoners enacted by Jeffrey

Lloyd-Roberts, Peter Hoare, Aleš Jenis, Florian Hoffmann, Alexander Kravets

and John Graham-Hall were all brought affectingly to life. Wigglesworth

delineated the score’s tensions and jagged edges with precision but did not

always allow the moments of lyrical release to surge with warmth.

For this listener, the opera’s real power lies in the moments when the

prisoners’ bitter alienation from the ‘real’ world is overcome, when

outside world and prison converge, such as when Šiškov recognises and

attacks Luka at the close and is reminded by the old prisoner that ‘He was

born of a mother too’, sobbing as he makes the sign of the cross over

Luka’s corpse, ‘There are bright moments in house of the dead.’ Such

moments affirm the value of humanity and the purpose of existence, even

amongst the lowest fallen.

As the score’s inscription states, in every creature there is a spark of

God. Warlikowski’s production fails to embody this small optimism which is

ever present in both the free and the captured.

Claire Seymour

Leoš Janáček: From the House of the Dead

Alexandr Gorjancikov - Willard W. White, Aljeja - Pascal Charbonneau, Luka

Kuzmič - Štefan Margita, Skuratov - Ladislav Elgr, Šiškov/Priest - Johan

Reuter, Prison Governor - Alexander Vassiliev, Big Prisoner/Nikita - Nicky

Spence, Small Prisoner/Cook - Grant Doyle, Elderly Prisoner - Graham Clark,

Voice - Konu Kim, Drunk Prisoner - Jeffrey Lloyd-Roberts, Šapkin - Peter

Hoare, Prisoner/Kedril - John Graham-Hall, Prisoner/Don Juan/Brahmin - Aleš

Jenis, Young Prisoner - Florian Hoffmann, Prostitute - Allison Cook,

Čerevin - Alexander Kravets, Guard - Andrew O'Connor; Director - Krzysztof

Warlikowski, Conductor - Mark Wigglesworth Designer - Małgorzata

Szczęśniak, Lighting designer - Felice Ross, Video designer - Denis

Guéguin, Movement director - Claude Bardouil, Dramaturg - Christian

Longchamp, Royal Opera Chorus and Orchestra.

Royal Opera House, Covent Garden; Wednesday 7th March 2018.