Despite all that, the production was greeted with general applause from audience and critics alike as a sensitive and thoughtful updating of Verdi’s 1871 grand opera. (Read my Opera Today colleague James Sohre’s review here .)

What a difference four years can make. The Zambello Aïda which opened in San Francisco in 2016 was graced by the same kind of multi-culty, anti-violence program notes that accompanied Glimmerglass’s. But the ideological edge had vanished. True, Radamès gave a Fascist salute at the climax of the Triumphal scene; but that edgy moment had vanished by the time the show arrived at the Kennedy Center last year.

Further softenings ensued before touch-down in Seattle: what we saw wouldn’t have troubled a 1950 audience, apart from the absence of elephants.

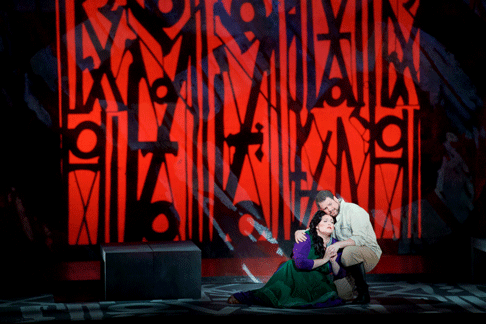

Elena Gabouri (Amneris) and Daniel Sumegi (Ramfis). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

Elena Gabouri (Amneris) and Daniel Sumegi (Ramfis). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

War and its agonies had been pretty much painted over, rendering Verdi’s stuffy but memorable opera as anodyne as a Midwestern Christian college musical: at the cost, granted, of depriving it of any dramatic impact at all.

That left us with half a dozen of Verdi’s most memorable tunes to occupy us for three and a half hours. We were diverted (or not) strictly to the extent the performers were capable of overcoming the incoherence of the staging and the faint but pervasive aroma of bad faith.

Most prepossessing of the Saturday evening cast I saw was David Pomeroy as Radamès. His voice is not particularly beautiful or powerful, but his stamina convinces one he could go on popping off ringing high As and Bs all night, and his youthful, open demeanor earns necessary sympathy for one of the most clueless heroes in the whole repertory.

Alfred Walker scored points for his dignity and dramatic declamation as the heroine’s prisoner father Amonasro. The same goes for bass Daniel Sumegi as the high priest Ramfis, towering over everybody else like the very incarnation of high dudgeon.

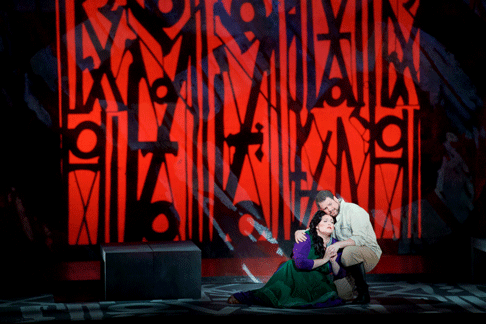

Alexandra LoBianco (Aida) and David Pomeroy (Radamès). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

Alexandra LoBianco (Aida) and David Pomeroy (Radamès). [Photo by Jacob Lucas]

As the title character Alexandra Lobianco sang the tender music of acts three and four with sweetness and warmth; in the first two acts, she was inaudible whenever the orchestra rose above mezzo piano. Burdened with silent-movie heroine make-up and blocking which kept her hovering timidly on the edge of the action, she seemed feebleness personified. It seemed impossible that fierce divas like Leontyne Price and Birgit Nilsson could have achieved fame in such a mousy role.

No such doubt could be felt in Elena Gabouri’s Amneris, Aïda’s rival for the hero’s love. Amneris is a severly conflicted woman; Gabouri made her a thoroughly disagreeable one as well. Her first appearance, marching around Egyptian military HQ and blaring with bad temper, set the tone for her whole performance.

John Fiore appears to be a “singer’s friend” type of opera conductor, giving telegraphic cues and pacing generously, at the cost of dramatic tension Jessica Lang’s choreography, most prominent in the Triumphal scene, is pretty, graceful, and cloying.

“Cloy” doesn’t cover the substitution of a covey of red-beret-wearing Cub Scouts for the libretto’s dancing Moorish slave-boys. They also feature in the climax of the Triumphal scene, along with a blizzard of gilded-vinyl confetti. Cute kids and confetti: that’s what I’ll remember from this production. Whatever the political incorrectness of Verdi’s original, it didn’t deserve this.

Roger Downey

Cast and production information:

Ramfis: Daniel Sumegi; Radames: David Pomeroy; Amneris: Elena Gabouri; Aida: Alexandra Lobianco; King: Clayton Brainerd; Messenger: Eric Neuville; High Priestess: Marcy Stonikas; Amonasro: Alfred Walker; Stage Director: E. Lauren Meeker, after the original staging by Francesca Zambello; Set Design: Michael Yeargen; Projections hangings, set pieces: RETNA (Marquis Duriel Lewis); Costumes: Anita Yavich; Lighting Design: Mark McCullough and Peter W. Mitchell; Choreographer: Jessica Lang; Chorus Master: John Keene. Seattle Opera Orchestra, John Fiore, conductor.