Otakar Ostrčil was a prominent Czech composer who has fallen into

obscurity. His dates, 1879-1935, span a key moment in the history of

Central Europe, for it was in 1918 that the Czech lands became part of the

new country of Czechoslovakia, independent of Austrian rule. In the

preceding decades, Czech writers and artists had often attempted to define

a national identity for themselves, as can be heard in many works of

Smetana and Dvořák. When national statehood arrived, composers

took one of several paths: some modeled their work on trends within the

European musical mainstream (e.g., symphonic poems in the manner of Liszt

or Strauss; or neoclassicism in the manner of Stravinsky and some of Les

Six), while others continued to explore ways of sounding distinctive and

different, for example by writing vocal music and opera using Czech texts

based on Slavic folk legends. The whole story is further enriched by the

fact that Prague had a substantial German-speaking population (including

many Jews), and even a German opera house, the New German Theater, which is

now known—after a number of name changes—as The Prague State

Opera.

Ostrčil, who established himself early on as a conductor and composer,

served as the music director at the Prague National Opera (i.e., the

Czech-speaking house) from 1920 till his death at the age of 56. He was

greatly admired for the precision of his conducting and for the open-minded

welcome he gave to a wide range of repertoire, from the comic operas of

Auber to a work for which he was roundly chastised in the press:

Berg’s Wozzeck. His 1933 recording of Smetana’s The Bartered Bride was at one point released on CD by Naxos but

seems to have been withdrawn, perhaps for contractual reasons.

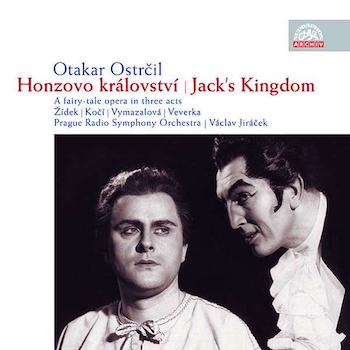

Ostrčil wrote a number of successful orchestral works and operas. Honzovo Království was the last of his

operas, and the present recording is a re-release of a superlative

recording made in 1954. The opera was a great success at its premiere in

1934, but Ostrčil died four months later, possibly in part because of

overwork. (The often-contentious Czech musical scene during the first half

of the twentieth century comes vividly to life in two scholarly books that,

I should confess, I had a hand in getting published: Opera and Ideology in Prague, by Brian Locke—no relation to

me!—and Bedřich Smetana: Myth, Music, and Propaganda,

by Kelly St. Pierre.)

In Honzovo Království (which has been variously

translated as “Johnny’s Kingdom” or “Jack’s

Kingdom”), Ostrčil distinguishes himself from most Western

composers by basing the libretto on “Ivan the Fool,” a

quasi-folktale published in 1886 by a fellow Slav, Leo Tolstoy. The story

tells of four siblings whom the Devil tries to manipulate for his own

nefarious purposes. Ivan, though seemingly dim-witted, is the one who

manages to out-maneuver the Devil. He ends up establishing a kingdom in

which there are no wars, and people who do physically demanding labor are

the first to be served dinner, whereas intellectuals and nobles (people

with soft, pale hands) have to be content with whatever is left over.

Ostrčil’s librettist, Jiří Mařánek, gave the

story a specifically Czech twist, in part by renaming the characters: most

notably, Ivan becomes Honza, a figure clearly derived from the character in

many Czech folk tales known as “Hloupý Honza,” i.e., Dull

Jack. (The name Honza, like Hans in German, derives from Johannes.)

Honza’s brothers are now called Ondřej (i.e., Andrew) and, a bit

oddly, Ivan. The fourth sibling, a mute sister, is omitted. Honza comes

across here as similar to another powerfully effective simpleton in Czech

culture: the title figure in Jaroslav Hašek’s novel The Good Soldier Schweik (1921-23).

The opera is compact, taking, in this recording, only 107 minutes. The

basic style reminds me at times of mid-career Prokofiev (e.g., The Prodigal Son) or the motoric ensemble scenes in Weill’s Mahagonny. On a basic musicodramatic level, the work follows

certain Wagnerian procedures that had become normative for many Western

European opera composers in the intervening half-century. In general, the

melodic lines are conversational, requiring clear enunciation more than

long-phrased breathing. There are exceptions, though, mainly in lyrical

passages for Honza,

the Princess (CD 2, track 3),

and

the slippery, multi-faceted Devil.

I might recommend to enterprising lyric tenors Honza’s soliloquy

that opens Scene 2.

Continuity is provided by several recurring themes and by richly elaborated

interludes between scenes.

(For example, the orchestral description, in Act 2, of the sadness that

has gripped the kingdom because—as the Constable has just

explained in spoken words—the princess is mysteriously ill: begin

at 0’50”.)

Passages of spoken dialogue over orchestral music, a technique known in the

opera world as melodrama, depart forcefully from the Wagnerian model and

help emphasize the modesty and directness of the folk-like story.

(Melodrama was a technique particularly cultivated by Ostrčil’s

teacher, Zdeněk Fibich.)

The spirits of hell converse with the devil from all parts of the

theater, using megaphones. On the recording, their speaking

voices—they are trying to cook up a war in Honza’s

peaceable kingdom—are made even creepier by some simple

electronic reverb.

(The YouTube track begins with a symphonic interlude; the conversation

begins at 2’13”.)

This recording, apparently the only one that Honzovo Království has ever been granted, was made in

the Prague radio studios in 1954 and was released on LP by Supraphon.

(It can be heard entire, in many segments, at YouTube, but they are not

arranged in any recognizable sequence.)

The performance under Jiráček is vivid and presumably reflects

the extensive series of staged performances that the work had received in

the Czech and Slovak lands up to that point. The work was first heard in

Brno, in 1934, then in Ostrava, and from 1935 onward in Prague. It was

given in German in 1937 in the aforementioned German-language opera house

in Prague.

The reissue of this recording on CD was made possible, according to a note

in the booklet, by Astrid Štúrová-Kočí, presumably

the daughter of

baritone Přemysl Kočí

. The latter performs the role of the Devil splendidly—acting and

singing all at once, all the way through, with witty understatement rather

than Boris Christoff-like overemphasis. The CD release coincides, surely

not by chance, with the hundredth anniversary of Kočí’s

birth. What a wonderful tribute to the memory of someone who was a major

artist in Soviet-era Czechoslovakia.

The Czech Radio website (radioteka.cz) offers for sale, on CD or as a

download, a Czech-language performance of Mozart’s Don Giovanni with Kočí in the title role.

The other cast members come across just as vividly, including Otava, who

sang his role here (Ondřej) at the opera’s first Prague

production, 17 years earlier. In the meantime, Czechoslovakia had

experienced almost unimaginable turbulence: occupation by the Nazis, mass

deportations for forced labor in Germany, persecution of political

resisters, the systematic murder of most of the Jewish population, and, in

the post-war years, the expulsion of most of the German population and the

beginnings of what would be four decades of repressive Communist

dictatorship. I can barely imagine the many different ways that this

anti-war opera may have resonated for Czechs and Slovaks in 1954.

The best-known of the singers is

the tenor Ivo Žídek

, in the title role. We hear him at age 28; he had been singing leading

roles since 18 and would continue to expand his repertory, and to perform

and record internationally, at the highest level, until age 59. His singing

nicely balances secure vocal production with a serene characterization and

touches of humor.

Indeed, the singing from the whole cast is light and clear, with little

trace of the “Slavic wobble” that I find tiresome in many

recordings from further east (e.g., Russia and Bulgaria). The spoken roles

seem to be taken by professional actors: they are superbly done. The

orchestra and chorus play and sing alertly. Occasionally the woodwind and

brass sections are not perfectly tuned, or the brass blare a bit. The

various solos for wind instruments and for violin are nicely characterized.

The sound quality is high-quality mid-1950s mono: clear, no distortion, but

with the orchestra a bit recessed instead of richly surrounding the voices.

Essay, synopsis (with helpful track numbers), and libretto, in Czech and

(mostly comprehensible) English. I would say that it is time for a more

modern recording, allowing us to appreciate the power and wit of the

orchestral writing more. (And of course some live performances, either on

stage or in concert.) But, if the vocal performances did not show the

detail and insight that they do in this recording, I suspect the work

wouldn’t come across half as well as it does here.

The second CD is filled out with a recording of Ostrčil’s

fascinating fourteen-section set of Variations for Orchestra, Op. 24

(1928), entitled “Křížová cesta,”which is

translated on the CD box as “Calvary.” Other sources list the

work’s title as “Golgotha.” Closer English approximations

would be “The Way of the Cross” or “The Stations of the

Cross.”

This mono recording of the Variations, by the Czech Philharmonic under

Václav Neumann in 1957, may have been the work’s first.

(Like the opera, it is available on YouTube in segments. Here is the

opening: “The Son of Man Is Condemned to Death.”)

The sessions took place in Dvořák Hall, in the famous 1886

building called the Rudolfinum. The 1100-seat hall has fine

acoustics—reflected in the good clear sound—and is the home of

the Czech Philharmonic (and of many Prague Spring events).

A stereo recording, likewise by the Czech Philharmonic under Neumann,

was released on CD in 1990 and re-released in 1995.

Carl Bauman, in the American Record Guide, at first found the work

“bombastic” but, upon re-listening, discovered “various

beauties” in it (March/April 1995). Each of the work’s fourteen

short sections is headed with a descriptive phrase describing a moment from

Christ’s last days, beginning with his being condemned to death and

ending with his entombment. The booklet essay suggests that Ostrčil

identified with Christ because of how he himself had suffered for the art

he loved.

The musicologist Martin Nedbal informs me that there have been, for

centuries now, “Calvary hills” constructed throughout Europe,

including several in what used to be Czechoslovakia. A Calvary hill often

consists of a cross (or three crosses) on a hill, and other markers and

chapels on the way toward the hill, for pilgrims who wish to reenact and

ponder Jesus’s last journey.

I found the 31-minute-long piece continuously engaging, especially when I

remembered to keep in mind the titles over each of the fourteen sections:

for example, in section 4, Jesus meets his mother Mary (Mahlerian sorrow,

beginning with the strings alone and then broadening out) and, in section

7, he collapses for a second time under the weight of the Cross (much

thrust and intensity, full orchestra). The work follows the traditional

list of 14 Stations (some based on medieval legends), not the more

carefully scripture-derived versions authorized by Pope John Paul II in

1991 and by Pope Benedict in 2007 (which purge, for example, the episode of

Saint Veronica wiping Jesus’s face with her

veil—Ostrčil’s section 6).

I am not sure I’ve yet fully grasped the variation process here,

aside from a very noticeable rising motive that begins most of the fourteen

sections. I was more aware of the expressive contrasts from one section to

another. Still, I look forward to listening again to this remarkable case

of a programmatic orchestral work that conveys a message at once religious

and highly personal.

I continue to be surprised to find so many fine, even exciting musical

works that are floating “out there” yet rarely, if ever, get

performed in North America. I am grateful daily to Thomas Edison and his

followers who perfected the medium that gives me so much joy and emotional

gratification—including these two works by a composer who was to me,

until now, just a name in books.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in

American Record Guide

and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke

is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s

Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems

Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two

books are

Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections

and

Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart

(both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and

the second is also available as an e-book.

‡

Click here for a review of Laci Boldemann’s Black Is White, Said the Emperor. Click here for a review of Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges.