24 May 2018

The Moderate Soprano : Q&A with Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam

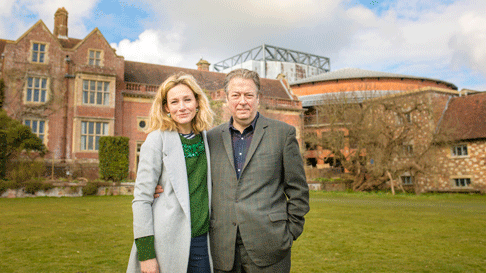

Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam play Audrey Mildmay and John Christie in David Hare’s play The Moderate Soprano which is currently at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London.

‘A brief history of song’ is the subtitle of the 2020 Oxford Lieder Festival (10th-17th October), which will present an ambitious, diverse and imaginative programme of 40 performances and events.

‘Signor Piatti in a fantasia on themes from Beatrice di Tenda had also his triumph. Difficulties, declared to be insuperable, were vanquished by him with consummate skill and precision. He certainly is amazing, his tone magnificent, and his style excellent. His resources appear to be inexhaustible; and altogether for variety, it is the greatest specimen of violoncello playing that has been heard in this country.’

Eboracum Baroque is a flexible period instrument ensemble, comprising singers and instrumentalists, which was founded in York - as its name suggests, Eboracum being the name of the Roman fort on the site of present-day York - while artistic director Chris Parsons was at York University.

‘There could be no happier existence. Each morning he composed something beautiful and each evening he found the most enthusiastic admirers. We gathered in his room - he played and sang to us - we were enthusiastic and afterwards we went to the tavern. We hadn’t a penny but were blissfully happy.’

When soprano Eleanor Dennis was asked - by Ashok Klouda, one of the founders and co-directors of the Highgate International Chamber Music Festival - to perform some of Beethoven’s Scottish Songs Op.108 at this year’s Festival, as she leafed through the score to make her selection the first thing that struck her was the beauty of the poetry.

“At the start, one knows ‘bits’ of it,” says tenor Mark Padmore, somewhat wryly, when I meet him at the Stage Door of the Royal Opera House where the tenor has just begun rehearsals for David McVicar’s new production of Death in Venice, which in November will return Britten’s opera to the ROH stage for the first time since 1992.

“Trust me, I’m telling you stories …”

When British opera director Nina Brazier tries to telephone me from Frankfurt, where she is in the middle of rehearsals for a revival of Florentine Klepper’s 2015 production of Martinů’s Julietta, she finds herself - to my embarrassment - ‘blocked’ by my telephone preference settings. The technical hitch is soon solved; but doors, in the UK and Europe, are certainly very much wide open for Nina, who has been described by The Observer as ‘one of Britain’s leading young directors of opera’.

“We need to stop talking about ‘diversity’ and think instead about ‘inclusivity’,” says Bill Bankes-Jones, when we meet to talk about the forthcoming twelfth Tête à Tête Opera Festival which runs from 24th July to 10th August.

The young Hong Kong-born British composer Dani Howard is having quite a busy year.

For Peter Sellars, Mozart’s Idomeneo is a ‘visionary’ work, a utopian opera centred on a classic struggle between a father and a son written by an angry 25-year-old composer who wanted to show the musical establishment what a new generation could do.

“Physiognomy, psychology and technique.” These are the three things that determine the way a singer’s sound is produced, so Ken Querns-Langley explains when we meet in the genteel surroundings of the National Liberal Club, where the training programmes, open masterclasses and performances which will form part the third London Bel Canto Festival will be held from 5th-24th August.

“Sop. Page, attendant on the King.” So, reads a typical character description of the loyal page Oscar, whose actions, in Verdi’s Un ballo in maschera, unintentionally lead to his monarch’s death. He reveals the costume that King Gustavo is wearing at the masked ball, thus enabling the monarch’s secretary, Anckarstroem, to shoot him. The dying King falls into the faithful Oscar’s arms.

A mournful Princess forced by her father into an arranged marriage. A Prince who laments that no-one loves him for himself, and so exchanges places with his aide-de-camp. A melancholy dreamer who dons a deceased jester’s motley and finds himself imprisoned for impertinence.

‘Aloneness’ does not immediately seem a likely or fruitful subject for an opera. But, loneliness and isolation - an individual’s inner sphere, which no other human can truly know or enter - are at the core of Yasushi Inoue’s creative expression.

What links Wagner’s Das Rheingold, Donizetti’s Anna Bolena, Mozart’s Don Giovanni and Cavalli’s La Calisto? It sounds like the sort of question Paul Gambaccini might pose to contestants on BBC Radio 4’s music quiz, Counterpoint.

Though she won praise from the literary greats of her day, including Thomas Hardy, Virginia Woolf, Ezra Pound and Siegfried Sassoon, the Victorian poet Charlotte Mew (1869-1928) was little-known among the contemporary reading public. When she visited the Poetry Bookshop of Harold Monro, the publisher of her first and only collection, The Farmer’s Bride (1916), she was asked, “Are you Charlotte Mew?” Her reply was characteristically diffident and self-deprecatory: “I’m sorry to say I am.”

“It lives!” So cries Victor Frankenstein in Richard Brinsley Peake’s Presumption: or the Fate of Frankenstein on beholding the animation of his creature for the first time. Peake might equally have been describing the novel upon which he had based his 1823 play which, staged at the English Opera House, had such a successful first run that it gave rise to fourteen further adaptations of Mary Shelley’s 1818 novella in the following three years.

It sounds like a question from a BBC Radio 4 quiz show: what links Handel’s cantata for solo contralto, La Lucrezia, Samuel Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape, and the post-punk band Joy Division?

The first two instalments of the Academy of Ancient Music’s ‘Purcell trilogy’ at the Barbican Hall have posed plentiful questions - creative, cultural and political.

Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam play Audrey Mildmay and John Christie in David Hare’s play The Moderate Soprano which is currently at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London.

What interested you about the play and taking on the role?

RA : In the first version of the play when John Christie comes on he’s described as short, fat, bald and wearing lederhosen and I thought, ‘That’s the part for me, I have to play that role’. So there’s that kind of infantile appeal of dressing up and changing one’s appearance as you can see [he says this while having his bald cap put on], that has always been an element of the appeal of acting to me. Maybe after this I’m giving it a break though [laughs]. But actually, it was getting to know the story both through the play and reading a biography of John Christie which was something I knew nothing about at all. I didn’t know how it was founded, I certainly knew nothing about how they kind of lucked out completely when the three probably best people in the world were escaping Nazi Germany, and came to work at Glyndebourne. And for me it became very clear that there was a real thing about standards, they really built and maintained standards. Whatever you feel about the ‘snobs on the lawn’ aspect of it, they raised the bar, I think, for everyone else.

NC : For me, it was telling a story about a woman who pushed her husband forward and just got on with it and even Gus Christie who currently runs the festival knows very little about his grandmother. She died in 1952 before he was born and all the stories are about his grandfather but very little is known about her. And indeed, for me as an actress to play a part that skips between 1934 and 1952 when that person was in two very, very different states is a fantastic acting challenge and that’s what interested me. And also, as a post-Brexit story the fact that this quintessentially English treasure was actually set up by two extraordinary Germans and an Austrian – as a message to the leaders of Brexit, I think it’s quite an important one…

So there’s the story of Glyndebourne as an institution…

RA : And I was also drawn in by John Christie as a character, he was the most extraordinary man. Deeply and naturally eccentric but also someone who wanted to do good, you know. I mean, in 1911 when he was 29 he had a car – when there weren’t that many cars on the road – a Daimler, and he took a trip to Bayreuth and he took two friends, two Eton schoolmasters, with him and there were no car ferries then of course, so the car was put on a barge and the barge was towed by a ferry and the three men sat in the car on the barge going across the channel and then drove to Bayreuth. I mean, it’s just rather wonderful. And he had a building company, he had an organ company, he installed electricity in Glyndebourne…

NC : I think he had an entrepreneurial, scientific mind and although he believed in hierarchy in so many ways, he also did extraordinary things, like he created a library for his staff at Glyndebourne because he believed that information and education should be for everybody…

Yes, his idea of opera as public service is an interesting one.

NC : But then it was always… in Italy, in Germany – it was popular music. It’s only in this country that we’ve created this sort of… it’s like Shakespeare really… you know it sometimes seems to before the educated and higher classes, which is nonsense. Shakespeare, although he was middleclass, was an actor working in theatres, in London, around the country, and they were playing to people, to every single class, it’s how it should be. It’s beautiful music – why should it be for one set of people and not another?

Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam at Glyndebourne [Photo © Piers Foley]

Nancy Carroll and Roger Allam at Glyndebourne [Photo © Piers Foley]

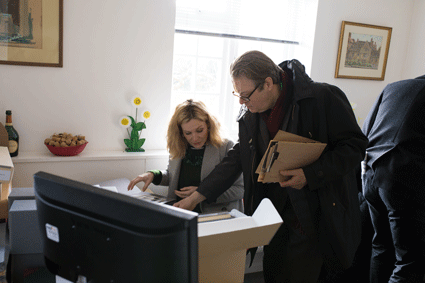

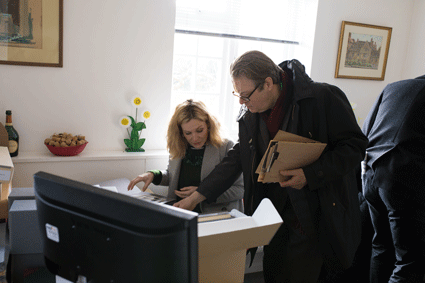

You visited the Glyndebourne archive when preparing for the role. What was interesting about that, what did you uncover?

NC : It was interesting to see lots of photographs of them, between 1934 and 1952 and the difference in her physicality, because she was in so much pain by then. But the photographs that I found fascinating were the 1934 ones when they were completely in their element and the kids were small – and when she was pregnant with their second child, they looked idyllically happy. And then 1952 he was still thriving and she was obviously much more sort of, held, and then 1962 when he was very ill he grew a big beard because he couldn’t shave any more…

RA : Also the difference in the building, the expanding opera house, so that every year from 1934 you look at the photographs, something has been added so that by the 1960’s they’d done lots of extensions, put in many rehearsal and dressing rooms, they put a gallery in the theatre… I think it ended up seating about 800 and started off at around 300. And the current building was built in the 90’s…

NC : The thing I loved in the second rehearsal period is that we were visited by John Cox who had assisted Carl Ebert and who was able to give us first hand knowledge of what it was like in its heyday. He said it was incredibly moving how committed everybody was and what an extraordinary ethos they had, which was very much the work of John Christie, of the two of them really -the family had an incredible ethos of creating a safe haven for singers, where they had these long rehearsal periods, and people were invited to stay in the family home and were treated as family. Everybody who was there felt incredibly loyal to the place, and John Christie had this incredible loyalty to people. So, he couldn’t have experienced that without going there and seeing this…. It was incredibly moving. And I think this is what the place inspires, it’s what the dream inspires.

Did you get to hear Audrey Mildmay singing?

NC : I heard Audrey Mildmay singing and that was just beautiful and it was really lovely to read some of her reviews from 1934, 1935, 1936 and everybody would always comment on the delicate honesty of her voice which in the play Rudolf Bing describes as Ausstrahlung, which is this essence, something about her which radiated, something from deep inside her that came out in her voice – but it didn’t have the power to fill a bigger space which is why Christie refers to her as a moderate soprano. There was this lack of power but actually the quality of the voice was very, very beautiful, and it was lovely to hear that. And one of the things I loved was seeing her travelling with her trunk when she was touring with the Carl Rosa company before she married John. There’s something about playing somebody who existed like that…

You mentioned you heard recordings of John Christie too…

RA : Yes, it was very useful to hear his voice but I can’t represent it accurately on stage because it would be too slow, as he was much older then, so I have to kind of invent something, but I invented it with the knowledge of what his voice sounded like when he was older which was great. And it was also great to be in Glyndebourne to soak up the atmosphere of the place.

So overall, a story worth telling?

NC: I think the main thing is it’s a fantastic story and so unexpected. The way that David [Hare] has written it… I think it comes to the audience almost like a stream of consciousness. Bob Crowley calls it a memory play but that suggests a gentleness and it’s not a gentle story. It’s robust and it’s about people passionately trying to make art. And I think that’s what interested David as well, as somebody who from a very young age worked against the odds to tell stories that he felt needed to be told and show the other side of the argument. It’s a beautiful thing and it comes at an audience from so many different angles so that at the end of two hours you’ve formed a picture, but it’s not a linear one – and that’s what makes it so interesting.