I recently reviewed for OperaToday.com two

recordings of Ravel's L'enfant et les sortilèges (which might

be freely translated as "The Boy Who Meets Objects and Creatures that

Magically Begin to Speak and Dance"). (Click

here

and

here.) I have also reviewed a very engaging Czech opera by Otakar Ostrčil,

based on a quasi-folktale by Tolstoy, in which the Devil seeks to seduce

three brothers into serving his own destructive ends.

Here is another such tall-tale opera, by a composer whose own life story

was full of all-too-real drama. Laci Boldemann (1921-69) was born in

Helsinki to a distinguished family that was half-Swedish, half-German. His

grandfather Arvid Järnefelt was a well-known Swedish author whose

sister Aino was married to the composer Sibelius. Boldemann studied in

Germany, then in England and Sweden, but, because of his German father, was

conscripted into the Nazi army. He became gravely ill on the eastern front.

Later, in Italy, he deserted and was brought to the United States and put

in a prison camp. After war's end, he settled in Sweden, where his maternal

grandparents lived. He succeeded in having a number of his works performed

by major orchestras and opera companies in Germany and Sweden. But he died

suddenly from complications after a gallstone surgery in Munich when he was

only 48.

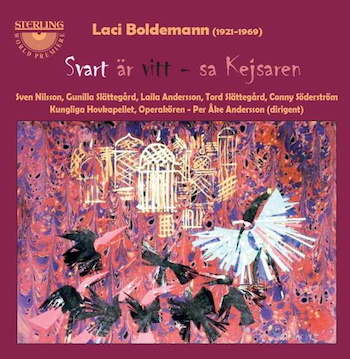

Black Is White, Said the Emperor

(Svart är vitt, sa kejsaren) is the first of his two

full-length operas. The present recording was made at the world-premiere

performance, on January 1, 1965, at the Royal Opera in Stockholm.

(It can be heard, broken into numerous segments, on YouTube.)

The scenario was drafted by Laci's wife Karin. It was fleshed out into a

libretto by Lennart Hellsing, a noted author of children's books and

nonsense literature. The informative notes are by Marcus Boldemann,

presumably Laci and Karin's son.

Boldemann's musical style is very traditional and straightforward,

generally shying away from modernist asperity. In Sweden, Boldemann is

still known today for some endearing choral songs. Lovers of solo vocal

music may know his fourteen-minute song cycle with orchestra:

Four Epitaphs

, Op. 10, using four poems from Edgar Lee Masters's Spoon River Anthology. (YouTube offers it, sung with rich tone

and pointed meaning by Anne Sofie von Otter, conducted by Kent Nagano.)

I will not try to summarize the eventful plot, which takes place in an

unnamed "Oriental" walled city, apparently somewhere along the Silk Road.

The storybook quality is already apparent in the list (above) of the

various characters, all of whom are "types" rather than

individuals-somewhat like the characters in Prokofiev's jaundiced

fairy-tale opera The Love for Three Oranges. Similarly, the

nameless Doctor who examines The Boy, while uttering meaningless

pseudo-medical chatter, seems like a less menacing version of the crazed

and likewise nameless physician in Wozzeck. But nobody and nothing

in this family-friendly opera stays menacing for long.

The work is built out of numerous short scenes, most of which involve quick

exchanges between several characters. There are few extended separable

numbers that could help advertise the opera, which is perhaps one reason

that it has sunk from view. Still,

The Boy gets a number of short songs that are quite appealing: often

diatonic or folkish-modal and built of easily grasped foursquare

phrases.

There is also

an immensely appealing tune that recurs several times

(e.g., CD 1, tracks 8 and 10) and that sounds like something out of a

Lehár operetta. The link just given comprises CD 1, track 8, which

begins with the Princess singing the tune; her words refer to the handsome

Prince who, riding by her window on a white horse, stole her heart. When

the Prince and Princess try to sing it together, the hot-headed emperor

cuts them short. (They get to sing the whole tune at the end of the opera,

and then walk off slowly into a happy future.)

The duet-interruption is typical: the opera is marked by much purposeful

discontinuity, and the discontinuity is sometimes emphasized by an

unexpected shift to a new harmonic area. The net result of all these

tuneful moments and sudden, disorienting surprises is refreshing to the

ear. Certain passages reminded me of works as varied as the Mephisto Waltz, Carmen, and Carmina Burana, and

Bernstein's Candide. None of these resemblances seem to have been

intended as recognizable allusions; rather, I suspect that they are the

result of Boldemann's open-mindedness and wide-ranging stylistic curiosity.

Similarly, some choral passages made me think-for whatever this is worth-of

certain ensembles in Puccini's Turandot, such as the Act 2 trio

for Ping, Pang, and Pong. At various points, the music briefly sounds

pseudo-Asian (or maybe Middle Eastern), then quickly veers back.

In short, there is always something interesting going on. Three ensembles

are particularly effective. The quintet near the end of Act 1 (track 20)

seems inspired, to good effect, by the Te Deum finale of Act 1 of Tosca.

A rhythmically intriguing trio in Act 2 (CD 2, track 7) is sung largely

in unison-sometimes unaccompanied, other times with alert orchestral

punctuation.

And a trio toward the end (CD 2, track 9), during which the Runner and the

Fool prepare to eject the Boy from the city, has the quality of a

distorted, possibly sardonic, Viennese waltz. Many sections of the score

are strongly continuous (quasi-developmental). In some of these, an

orchestral instrument or section of the orchestra expands on a phrase that

a character has just sung or gives it a new twist.

Typical for Sweden in the 1960s, there is a "techno" element: the brief

appearance of electronic sounds near the end of the opera, when an

auspicious star is seen in the sky. (

Click here and forward to 2'35"-orchestra then yielding to electronic

tape.

) The implication is that the emperor has seen the astonishing, noisy Star

announcing Jesus's birth. He removes his crown, places it on the Boy's

head, and marches off in the direction of the Star, thus apparently

becoming one of the famous Three Kings who, bearing gifts, visit the Christ

child.

Electronically derived sounds, a high-modern resource, had been used six

years earlier in a Swedish opera whose recording was widely reviewed at the

time: Karl-Birger Blomdahl's outer-space fantasy Aniara.

Blomdahl's opera got a second recording in 1985 (on Caprice, conducted by

Stig Westerberg). I suspect that Black Is White is at least as

worthy of a modern recording and of some staged performances. Christmastime

might be an apt season, given the appearance of the Star near the work's

end. Perhaps the brief but rather crude electronic track (which the

composer did not create; the realization here is credited to Karl-Otto

Valentin) could be replaced by something more sophisticated, in order to

prevent the work from being forever anchored to the era of Sputnik and the

Univac computer.

The current recording has fine presence, despite having been made during a

stage performance more than fifty years ago. The singers are all vivid

exponents of their roles, with sharply differentiated voices: for example,

the Runner is a character tenor, quite different from the Prince, a lyric

tenor. Gunilla Slättegård is a constant pleasure as The Boy: her

sound is as clear and sweet as a mountain stream. She made her debut at the

Royal Swedish Opera in this role and, under the name Gunilla Wallin, went

on to sing major roles by Mozart and others there until 1989. The veteran

bass Sven Nilsson brings to the role of the Emperor great authority, honed

over the years in operas and spoken plays. (His Daland is preserved on

Naxos's release of a 1950 Flying Dutchman performance at the

Met

conducted by Fritz Reiner and starring Hans Hotter and Astrid Varnay.) The

mikes occasionally pick up light laughter from the audience. A modern

recording would give the orchestra (which seems of chamber proportions)

more roundness and richness, but I wouldn't want that to happen at the

expense of the wonderfully precise characterizations that we hear here, in

voices and orchestra alike.

There are two extensive booklets. One contains the libretto, with

translations into English and German that are frankly announced as "raw"

(meaning: rough)! The English translation is comprehensible but full of

misspellings (inamoured, turikey) and confusing usages: it uses "port" to

mean a palace gate, and "rideau or veil," in the stage directions, to mean

"curtain or scrim." And what, I wonder, does the Emperor have in mind when

he threatens to turn the Boy and members of the court into "ghaith birds"?

The other booklet contains Marcus Boldemann's essay, a first-rate synopsis

(with track numbers), and bios of the composer, librettists, and

performers. Four lively sketches by the opera's original set designer,

Hermann Sichter, plus a photo of the Emperor in costume, help us visualize

our way into this remarkably fresh-sounding opera from 1965.

I recommend the recording to anybody-child or adult-who is curious about

what an opera can be like when it is not so much serious or comical as . .

. wild (and tuneful and colorful and entertaining)!

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in

American Record Guide

and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke

is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester's

Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems

Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two

books are

Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections

and

Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart

(both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and

the second is also available as an e-book.