And difficult Henze’s opera is. There is an heroic orchestra — batteries of brass, batteries of percussion, harps, pianos, guitars, it is after all the destruction of the founding family of one of ancient Greece’s greatest cities in the retelling of the last play of one of Greece’s greatest tragedians, Euripides! Not to mention two tone rows (yes, Henze was a serial composer) that configure the stark world of Pentheus, king of Thebes and the colorful world of Dionysus his challenger.

Euripides’ Bacchae was recast as an opera libretto for Henze by W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, who provided the libretto for The Rake’s Progress and texts for Benjamin Britten. Thus here as well are the expected discussions, rather fixations on repressed sexual realities.

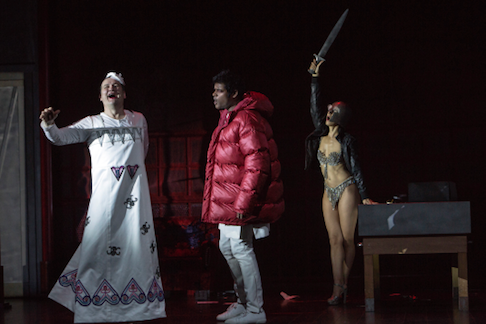

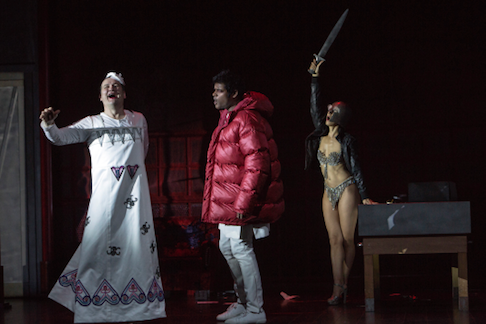

King Pentheus dressed as a woman, Dionysus plus a bacchanalia spirit (mute role)

King Pentheus dressed as a woman, Dionysus plus a bacchanalia spirit (mute role)

Essentially Semele, great grand daughter of Cadmus, founding king of Thebes, was murdered while giving birth to a son who may be the son of Zeus, and therefore a god, or maybe not. Cadmus abdicated naming Semele’s sister Agave’s son Pentheus as the new king. Pentheus has complicated feelings about his mother who is pretty complicated herself. A challenger appears who may be the god Dionysus. Everyone joins his cult. Pentheus disguises himself as a woman to learn about the cult. He is discovered by a band of women led by his mother who tear him to pieces believing that he is a lion. Dionysus removes his mother Semele from her earthly tomb and takes her to Olympus to join him as a god.

With all this on his mind Henze needed far more than his two tone rows, thus he mined musical and operatic traditions to embellish and enrich his musical manifestation of the Auden/Kallman take on the Euripides’ Bacchae. Vocal lines are comprehensible, and there actually is a sort of bel canto. There are occasional, quite beautiful arias within the opera’s symphonic structure. Bach’s St Matthew’s Passion is oft quoted, Mahler like textures and harmonies are discernible, and by musical miracle we even arrive at a momentary, truly magnificent 6/4 chord (second inversion of a triad) during Semele’s assumption!

It is magnificent, complex, highly expressive music that painstakingly delves into the psychological depths of insecure men and women, of obsession, and into the psychologies of mass social phenomena and the resulting human debasement.

But the final scene of the opera is in fact wonderfully liberating, indeed moving as Dionysus leaves Thebes and abandons the cult he has founded. He commands Persephone to open the gates of hell and release his mother that she may triumphantly unite with him upon Olympus.

Mounting Henze’s setting of the Auden/Kallman’s neurotic tale of infanticide in the massive stone world of the old riding school was a wondrous gift to famed Polish stage director Krzysztof Warlikowski. He simply spread it all out across the expanse of the riding school paddock, The a vista crypt and shrine of Semele on the far left, the private bedroom (his neurotic inner life) of King Pentheus on the far right and in between three palace rooms where the founding dynasty of Thebes was destroyed. The massive upper reaches of the riding school galleries became a metaphorical mount Cithaeron.

Henze’s choruses were crucial players in the drama, not spectators, though the chorus did begin the evening as spectators filing into the first two rows of the auditorium as the citizens of Thebes praising their new king. They quickly left and little by little they joined the Dionysian cult as did Thebes founder Cadmus, deftly enacted by venerable bass Willard White who was in good voice.

The palace prophet Tiresias — blind of course — was played by Austrian tenor Nikolai Schukoff who cross-dressed as the fey Calliope of the Intermezzo. Cadmus’ granddaughter Agave was convincingly, even heroically portrayed by Frankfurt Opera’s dramatic mezzo soprano Tanya Ariane Baumgartner. Her weaker sister Autonoe was sung by Berlin’s Komischen Oper’s Vera-Lotte Böcker.

Agave as Venus in Intermezzo, with Adonis, Persephone and Calliope

Agave as Venus in Intermezzo, with Adonis, Persephone and Calliope

A more complicated if less defined character was Pentheus’ Captain (of the royal guard) sung by Hungarian bass-baritone Károly Szemerédy who doubled as the Adonis in the Intermezzo in which Dionysus’ magic mirror shows to Pentheus the unbridled sexuality of his mother — a cunningly staged scene by Warlikowski that video-mirrored the Intermezzo in black and white from its enactment far stage left onto a wall far stage right.

Pentheus’ wet nurse Beroe, sung by Dutch mezzo Anna Maria Dur, was another complex character. Hera, Zeus’ wife impersonates Beroe so that she could intimidate Semele into demanding to see her lover (Zeus) thus destroying herself. Yet Beroe expresses blind, uncomplicated maternal love for Pentheus earning our sympathy.

Canadian Opera’s baritone Russell Braun brought unbridled commitment to his portrayal of the weak, sexually repressed King Pentheus, moving from impotent authority to loss of identity, from fulfillment as a woman to honesty as a lost man. Sri Lankan-American tenor Sean Panikkar brought full spectrum to Dionysus, from cunning manipulator to the loving son of the mother he never knew.

Henze’s score is fiendishly difficult, for its singers and for its orchestra. Conductor Kent Nagano marshalled the always impressive forces of the Vienna Philharmonic into a convincing performance, simultaneously chorus master Huw Rhys James conducted (from the pit) the 100 or so voices of the concert choir of the Vienna State Opera in its huge chorus role.

Michael Milenski

Additional production information:

Sets: Christian Schmidt; Costumes: Reinhard von der Thannen; Lights: Stefan Billiger

Grosses Festspielhaus, Salzburg, August 13, 2018.

![n, Hanna Schwarz as Pique Dame [All photos copyright Ruth Walz, courtesy of the SBrandon Jovanovich as Hermanalzburg Festival]](http://www.operatoday.com/Bassarids_Salzburg1.png)