The vitriolic Berlioz, still smarting from the failure of his own Benvenuto Cellini after just ten performances at the Opéra, may

have dismissed Donizetti’s La Fille du Régiment as

trivia, but the rest of Paris was smitten when the opera premiered at the

Opéra-Comique on 11th February 1804. Even the previous

dismissive Mendelssohn had to admit Donizetti’s talent: ‘I am afraid I like

it … Do you know, I should like to have written it myself.’

Opera della Luna’s Artistic Director certainly takes the Donizetti’s

‘little opera’ seriously: his production, first seen in 2014 and now

slightly revised, treats the opera with a light and loving touch as it

transfers the action from the nineteenth-century Swiss Tyrol to the desert

mountain ranges of California during the 1950s.

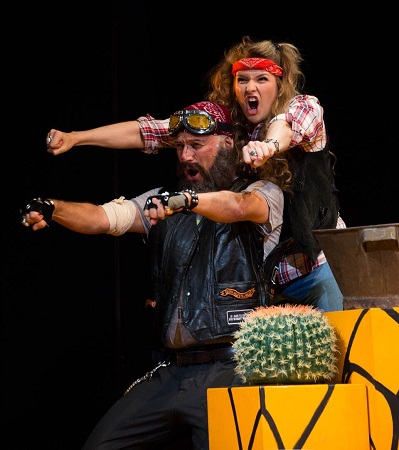

The abandoned baby, Marie, is not found by a corps of military muscle but

by a gang of leather-clad bikers, The Regiment, who are engaged in

non-mortal combat with their rivals, The Wild Cards. Think

Donizetti meets West Side Story. Ian Wilson’s lighting fetchingly

contrasts the heat-laden cobalt blue sky with the ochres of the sun-cracked

scorched earth from which a few prickly catci sprout. When we transfer, in

Act 2, to the Berkenfield Mansion, where Marsha plots with Dulcie

Crackenthorpe to marry off her reclaimed ‘niece’ to Dulcie’s son, the

desert makes a surprisingly effective home for the grand piano.

The cast’s American accents - in both the spoken text of Clarke’s

colloquially spicy translation and in the musical numbers - are convincing

and consistent, and none more so than the warm drawl of Charles Johnston as

Sulpice, the President of The Regiment. Despite the aggressive

posturing and knuckle-rings, beneath the beard and bandana this Sulpice is

a gentle giant, and Johnston’s warm baritone was one of the pleasures of

the evening - equalled by his easy presence of stage and dramatic nous. He

leads a Regiment who are full-voiced and proud, but whose bikes are as big

as their hearts - despite the rather limiting dimensions of Wilton’s’

stage, they glide their wheels in neatly choreographed formations with just

the right blend of elegance and heft - and the stoical, shoulder-sobbing

upon the enforced departure of Marie is both touching and side-splitting.

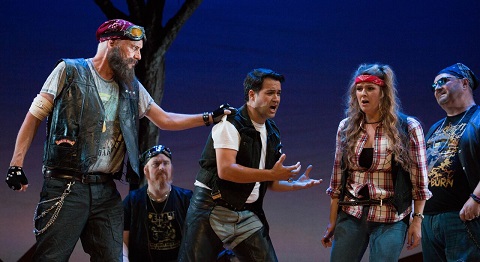

Charles Johnston (Sulpice), Jesus Alvarez (Tonio), Elin Pritchard (Marie). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Charles Johnston (Sulpice), Jesus Alvarez (Tonio), Elin Pritchard (Marie). Photo credit: Robert Workman.

Johnston’s wise Sulpice also brings out the best in Katharine

Taylor-Jones’ Marsha Berkenfield. Glammed up in primary hues and polka

dots, Taylor-Jones steers clear of caricature and uses her beautifully soft

and sweet contralto to show us Marsha’s scruples and sincerity.

She and Robert Gilden’s Mr Hortensius make a well-balanced double-act.

Gilden’s butler minces gloriously, surreptitiously swigging a generous glug

of martini from the ‘survival-flask’ when his mistress is lost in the

mountains, and shows suave sycophantic servitude when ensuring the guests

at Marsha’s soirée have their champagne cravings satisfied. He has the

audience in stitches during the Act 2 overture with his oh-so-precious

peeling of the paper which wraps the oranges destined for the silver

fruit-bowl atop the Steinway, polishing each with a brisk flick of limp

wrist and feather duster. Just how he swallowed the banana that made a

surprise appearance in the fruit-box, without apparent moving his mouth, I

can’t begin to imagine.

As the titular ‘foundling-with-fathers’, Elin Pritchard wore her denim and

biker-boots like a natural, her gleeful grin and terrific pout evincing

tomboyish charm. Marie’s manic passion for wheels took a musical turn - who

knew that a singer’s rolled ‘r’s could accelerate into a “V-rrr-oom!”

“Wow!” Marie screamed in the middle of her singing lesson, when Sulpice

distracted her from her middle-class aspirational pastimes with the

gleaming illustrations in his copy of Ultimate Road Machines.

In fact, memories of home released pent-up frustrations and repressed

energies. Literally hemmed in by gawky hem-line, Pritchard stepped on the

gas and threw restraint - and her lesson music - to the wind. She kicked

off her cotton socks and turned Sulpice’s motorbike encyclopaedia into a

tennis racket: poor Hortensius’ face said it all, as his carefully arranged

orange tier was dismantled and hurtled into the audience. Pritchard enjoyed

herself immensely: she has a powerful soprano which is full of colour and

can hit the highs and make them sing. She moved easily through climbs and

peaks and negotiated Donizetti’s curlicues smoothly, but was equally

persuasive in Marie’s quiet aria of reflection as she tries to reconcile

herself to her fate.

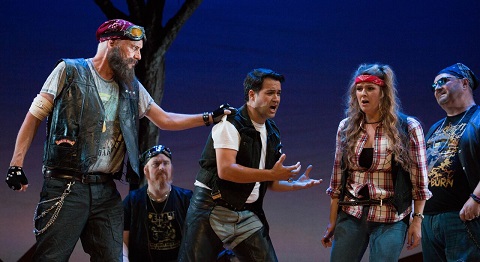

Charles Johnston (Sulpice), Jesus Alvarez (Tonio), Elin Pritchard (Marie). Photo credit: Nathan Cox.

Charles Johnston (Sulpice), Jesus Alvarez (Tonio), Elin Pritchard (Marie). Photo credit: Nathan Cox.

In his clean chinos and white ti-shirt, Jesus Alvarez’ Tonio - a Hispanic

immigrant in this production - was certainly out-of-place and an unwanted

interloper when he wandered into the bikers’ turf territory. Alvarez played

it safe initially, but demonstrated plenty of stamina and courage, nailing

each and every one of his high Cs which were well-supported and ringing.

The vocal acrobatics turned out to be an initiation rite into the Regiment’s gang and he passed with flying colours, slipping with

ease into his black bomber jacket. Alvarez didn’t always persuade me with a

legato line, and his English diction was less than ideal, but he blended

well in the ensembles and was an endearing Tonio.

Dulcie Crackenthorpe’s ghastly snobbishness was brilliantly captured by

Philip Cox, and he was matched for ‘style’ by Jeremy Vinogradov’s

self-loving Mrs van der Gelder. As her husband, the Governor of California,

Richard Woodall sported a finely sculpted moustache and showed surprisingly

balletic grace on the ballroom floor.

Conductor Benedict Kearns had his finger securely on the Donizetti pulse

and his tempi were wisely judged, only occasionally leaving the singers

rushing a little to catch up. The eleven instrumentalists were not housed

in the most comfortable performance space - the percussion and bass were

shoved into a cupboard under the balcony - but this didn’t hamper the

orchestral performance one iota or dampen their obvious enjoyment of the

music.

The overture was confidently played by the small ensemble, kicking off with

a ringing horn solo from Kevin Elliott. It took Kearns a while to get the

measure of the Hall’s acoustic, and the string ensemble was a little bass

heavy at times, but if the orchestra overshadowed Marsha and Hortensius in

their opening duet (for reasons of length and logic the opening chorus of

Tyrolean citizens praying for safety while a battle between their

countrymen and marauding French troops is one of Clarke’s neat excisions)

then the players soon dropped down to achieve a more judicious balance.

There were expressive solos from oboist Peter Facer and cellist Joanna

Twaddle, deepening the pathos of the more sentimental dramatic moments.

Jeff Clarke and the terrific cast gave us a joyful evening of sunny

high-spirits. No wonder the bikers let rip with some ritual air-punches and

it was smiles all round at the close. Once again, Opera della Luna served

up some seriously slick comedy.

Claire Seymour

Donizetti: The Daughter of the Regiment

Marsha Berkenfield - Katharine Taylor-Jones, Mr Hortensius - Robert Gildon,

Sulpice - Charles Johnston, Marie - Elin Pritchard, Tonio - Jesus Alvarez,

Dulcie Crackenthorpe - Philip Cox, The Governer of California - Richard

Woodall, Mrs van der Gelder - Jeremy Vinogradov, The Regiment (Tulip -

Richard Belshaw, Beef - Philip Cox, Tiny - Graham Stone, Crispy - Martin

George, Rabbit - Jeremy Vinogradov, Lump - Richard Woodall); director -

Jeff Clarke, conductor - Benedict Kearns, set designer - Graham Wynne, costume

designer - Maria Lancashire, lighting designer (for Wilton’s) - Ian Wilson,

Orchestra of Opera della Luna.

Wilton’s Music Hall, London; Tuesday 31st July 2018.