15 Aug 2018

Lohengrin at Bayreuth

Three electrifying moments and the world is forever changed.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

The doors at The Metropolitan Opera will not open to live audiences until 2021 at the earliest, and the likelihood of normal operatic life resuming in cities around the world looks but a distant dream at present. But, while we may not be invited from our homes into the opera house for some time yet, with its free daily screenings of past productions and its pay-per-view Met Stars Live in Concert series, the Met continues to bring opera into our homes.

Music-making at this year’s Grange Festival Opera may have fallen silent in June and July, but the country house and extensive grounds of The Grange provided an ideal setting for a weekend of twelve specially conceived ‘promenade’ performances encompassing music and dance.

There’s a “slide of harmony” and “all the bones leave your body at that moment and you collapse to the floor, it’s so extraordinary.”

“Music for a while, shall all your cares beguile.”

The hum of bees rising from myriad scented blooms; gentle strains of birdsong; the cheerful chatter of picnickers beside a still lake; decorous thwacks of leather on willow; song and music floating through the warm evening air.

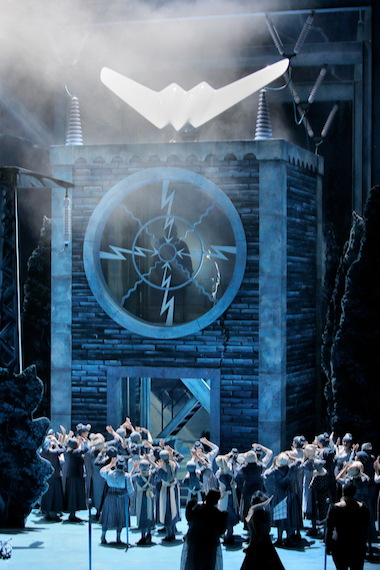

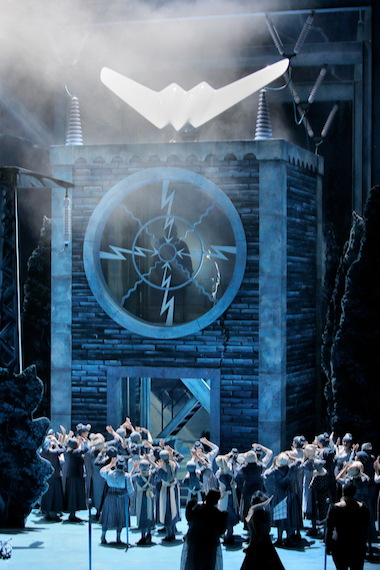

Three electrifying moments and the world is forever changed.

Elsa is to be burned at the stake for murdering her brother, the fire is lighted. A cataclysmic electrical display travels across live points on monumental insulators and conducts itself through the town clock upon which a white space ship in the vague shape of a giant moth alights (other times a swan). Elsa’s savior appears in street clothes wearing insulated gloves.

Matched by an orchestral display of appropriate proportion.

He sings but he is not tenor Roberto Alagna who would have brought his unique colors and attitudes to Lohengrin had he not cancelled three days before rehearsals were to begin. There were moments throughout evening when I could hear his voice and sense his persona, matched in so many ways to the lyricism, vulnerability and delicacy of mezzo Waltraud Meier, Wagner’s Ortrud in this production.

Polish tenor Piotr Beczala stepped in to sing his first Lohengrin. His was a spell binding portrayal, heroic in its youthful strength, of unflagging voice in its careful shaping of the subtleties of text, and profoundly moving as the tragic, failed savior of the duchy of Bramant.

In this production created by German visual artists (painters) Neo Rauch and Rosa Loy, and American stage director Yuval Sharon one is not sure how the concept evolved — to wit moths (like people) are attracted to light (enlightenment) and executed (confused) by touching its energy. As unlikely a metaphor as it was, finally, it was a powerful metaphor that took us to Wagner’s philosophical plain and kept us there, director Sharon staging the action in stultifying ceremonial symmetry to achieve solid inviolable confirmation.

The phenomenal energy introduced by Lohengrin burst the bindings holding Elsa to the stake, and this was the same energy that was to have bound her forever to Lohengrin, pulses of electricity rushing along cables into the marriage chamber as he bound her with electrical cord to a giant illuminated insulator.

Piotr Beczala as Lohengrin and Anja Harteros as Elsa

Piotr Beczala as Lohengrin and Anja Harteros as Elsa

But Ortrud had come to Elsa in a truly magical garden (mysterious foliage moving every which way) to warn her of the dangers and the insult of accepting what she must not know. Conductor Christian Thielemann convincingly led the two women to an understanding that overcame the mandate imposed on Elsa of blind acceptance of the imposed order. The radical strength imparted by Ortrud overcame Elsa’s blind ties to Lohengrin, and she was heroically able to burst the binding of matrimony in a truly magisterial musical climax.

And in the last scene Ortrud, bound to the stake to die for her participation in Telramund’s pagan, dark world, heroically burst her bindings as well. Stage director Sharon’s world is blatantly politically correct, and always a few clever and significant steps beyond Wagner’s Romantic philosophy. Mr. Sharon simply changed Richard Wagner’s ending — Elsa does not fall dead.

In a final sacrificial act Lohengrin attaches a backpack of pure light to Elsa who, with Ortrud goes forth to found, presumably, a new, enlightened world, leaving behind, presumably, the combative, male centricity of the old order. Wagner’s dream of theater as a religious rite was fully achieved and the audience went wild with its new liberation, with its rebirth into a new, maybe better world — though a world unfortunately left undefined, and certainly unquestioned.

Note that Cosima Wagner (Richard's widow) famously went forth to preserve Wagner’s nationalistic ideals, making Bayreuth a foundation of Nazism. Note that Katerina Wagner today preserves the Wagner legacy and Bayreuth canon, and she preserves its firm national identity (no English to help a significant if small percentage of foreigners). Though Mme. Wagner has embraced electrical rather than gas lighting, and installed the latest stage machinery she has not added supertitles, thus betraying her great grandfather’s greatest theatrical ambition — an immediacy of comprehension.

Lohengrin, Ortrud, Telramund, King Heinrich, a herald, Elsa

Lohengrin, Ortrud, Telramund, King Heinrich, a herald, Elsa

Painters Rauch and Loy’s world is brilliantly old fashioned in feel, painted drops the primary background. Sophistication abounded in the use of scrims, shadowy moving pieces and color. Architectural pieces and costumes superimposed the Medieval upon the Romantic, layered the industrial and modern, and confused the real with the fantastic, to wit pale, moth colored Elsa (well, until she was electric orange), not to overlook the moth wings, subtly worn by all the principles as if natural attire.

All the magic of Bayreuth’s Festspielhaus was in place — the hidden orchestra of absolute musical authority, the present acoustic that permits casting of artists of intimate intensity like 62 year-old Waltraud Meier as Ortrud whose voice very rarely betrayed its age and always found the full depth of character. The persuasive soprano of Anja Harteros kept Elsa as the focal point of this production, clearly sailing over the ensembles, never losing its inherent sweetness. Polish Tomas’s Konieczny had little to do other than be a force of darkness, Georg Zeppenfeld as King Heinrich was the benign moderator.

Conductor Christian Thielemann miraculously accomplished the required musical persuasion.

Michael Milenski