30 Sep 2018

ENO's Salome both intrigues and bewilders

Femme fatale, femme nouvelle, she-devil: the personification of patriarchal castration-anxiety and misogynistic terror of female desire.

English Touring Opera are delighted to announce a season of lyric monodramas to tour nationally from October to December. The season features music for solo singer and piano by Argento, Britten, Tippett and Shostakovich with a bold and inventive approach to making opera during social distancing.

This tenth of ten Live from London concerts was in fact a recorded live performance from California. It was no less enjoyable for that, and it was also uplifting to learn that this wasn’t in fact the ‘last’ LfL event that we will be able to enjoy, courtesy of VOCES8 and their fellow vocal ensembles (more below …).

Ever since Wigmore Hall announced their superb series of autumn concerts, all streamed live and available free of charge, I’d been looking forward to this song recital by Ian Bostridge and Imogen Cooper.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

Although Stile Antico’s programme article for their Live from London recital introduced their selection from the many treasures of the English Renaissance in the context of the theological debates and upheavals of the Tudor and Elizabethan years, their performance was more evocative of private chamber music than of public liturgy.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Evidently, face masks don’t stifle appreciative “Bravo!”s. And, reducing audience numbers doesn’t lower the volume of such acclamations. For, the audience at Wigmore Hall gave soprano Elizabeth Llewellyn and pianist Simon Lepper a greatly deserved warm reception and hearty response following this lunchtime recital of late-Romantic song.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

For this week’s Live from London vocal recital we moved from the home of VOCES8, St Anne and St Agnes in the City of London, to Kings Place, where The Sixteen - who have been associate artists at the venue for some time - presented a programme of music and words bound together by the theme of ‘reflection’.

'Such is your divine Disposation that both you excellently understand, and royally entertaine the Exercise of Musicke.’

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

‘And there was war in heaven: Michael and his angels fought against the dragon; and the dragon fought and his angels, And prevailed not; neither was their place found any more in heaven … that old serpent … Satan, which deceiveth the whole world: he was cast out into the earth, and his angels were cast out with him.’

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

There was never any doubt that the fifth of the twelve Met Stars Live in Concert broadcasts was going to be a palpably intense and vivid event, as well as a musically stunning and theatrically enervating experience.

‘Love’ was the theme for this Live from London performance by Apollo5. Given the complexity and diversity of that human emotion, and Apollo5’s reputation for versatility and diverse repertoire, ranging from Renaissance choral music to jazz, from contemporary classical works to popular song, it was no surprise that their programme spanned 500 years and several musical styles.

The Academy of St Martin in the Fields have titled their autumn series of eight concerts - which are taking place at 5pm and 7.30pm on two Saturdays each month at their home venue in Trafalgar Square, and being filmed for streaming the following Thursday - ‘re:connect’.

The London Symphony Orchestra opened their Autumn 2020 season with a homage to Oliver Knussen, who died at the age of 66 in July 2018. The programme traced a national musical lineage through the twentieth century, from Britten to Knussen, on to Mark-Anthony Turnage, and entwining the LSO and Rattle too.

With the Live from London digital vocal festival entering the second half of the series, the festival’s host, VOCES8, returned to their home at St Annes and St Agnes in the City of London to present a sequence of ‘Choral Dances’ - vocal music inspired by dance, embracing diverse genres from the Renaissance madrigal to swing jazz.

Just a few unison string wriggles from the opening of Mozart’s overture to Le nozze di Figaro are enough to make any opera-lover perch on the edge of their seat, in excited anticipation of the drama in music to come, so there could be no other curtain-raiser for this Gala Concert at the Royal Opera House, the latest instalment from ‘their House’ to ‘our houses’.

"Before the ending of the day, creator of all things, we pray that, with your accustomed mercy, you may watch over us."

Femme fatale, femme nouvelle, she-devil: the personification of patriarchal castration-anxiety and misogynistic terror of female desire.

It’s not surprising that a twenty-first-century opera director might want to find ways of re-imagining Salome which do not simply reproduce fin-de-siècle obsessions and neuroses. Adena Jacobs’s new production for English National Opera eschews the quivering sensuousness of Flaubert, Huysmans, Moreau, Beardsley, Wilde, Klimt et al - overlooking, in so doing, Richard Strauss’s own chromatic writhing and lurid orchestrations - and replaces their visual and literary lavishness with defiant feminist imagery. Barbies and Bronies both take a bashing, as this insolent teenager in black leather hot pants gives as good a gaze as she gets, wielding a phallic baton in brutal defiance and steely self-definition.

Ella Ferris Pell - Salome. Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Ella Ferris Pell - Salome. Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacobs isn’t the first to attempt, as Lawrence Kramer puts it, ‘to appropriate the Salome complex on Salome’s behalf’. [1] Kramer draws attention to a portrait of Salome which the American artist Ella Ferris Pell exhibited in 1890 and which Bram Dijkstra reproduces on the cover of his book Idols of Perversity, citing Dijkstra’s suggestion that, ‘Pell's Salome makes a revolutionary statement by being nothing but the realistic portrait of a young, strong, radiantly self-possessed woman who looks upon the world around her with confidence … [Such a woman] was far more threatening, far more a visual declaration of defiance against the canons of male dominance than any of the celebrated vampires and viragoes created by turn-of-the-century intellectuals could ever have been.’

Dijkstra’s words largely seem to sum up the intentions of Jacobs and designer Marg Horwell in their feminist commandeering of Strauss’s opera, though of course the twenty-first-century context supplies its own particular imagery. We begin in near-darkness, Stuart Jackson’s Narraboth yearningly proclaiming his obsessive love for the beautiful princess of Judaea, surrounded by a crowd of fellow-fans and Instagram-followers who, confined within a roped-off enclave, await the arrival of their idol. Above is suspended what at first seems to be a fish-tank, though grainy glimpses of the sinuous movements of a woman bathing gradually come into semi-focus.

At last, Salome herself becomes visible through the blackness. She watches herself being watched. Given what will follow, perhaps she should have learned a lesson from the long list of troubled, contemporary ‘celebrities’ who have found, with sometimes tragic consequences, that though playing with one’s public personae gives illusions of control, it’s not so easy to exorcise patriarchy and find one’s authentic self.

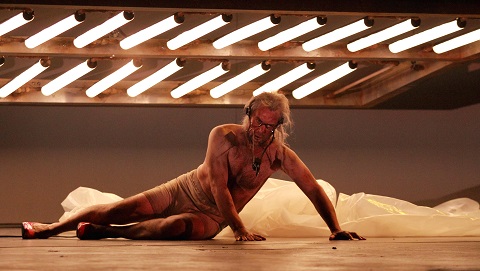

David Soar (Jokanaan). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

David Soar (Jokanaan). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Indeed, out of the blackness, via a reverberant loud-speaker, come the stirring warnings of David Soar’s resonant and arresting Jokanaan. Allison Cook’s Salome is drawn like a fly to an electric zapper and descends to the Baptist’s den of incarceration. Only the feet of the filthy prisoner are visible, protruding from a grubby tarpaulin - presumably preventing the prophet from being fried alive by the fierce lights burning above him. His feet are crushed into shocking pink stilettos and his mouth, so feared by Herod, so fetishized by Salome, is magnified on the rear wall. When he staggers from beneath his protective sheet we see that a pin-hole camera is strapped to Jokanaan’s face - a sort of scold’s bridle - relaying projections of the potent orifice.

The portentous confrontation between redeemer and radical unfolds: as Salome luxuriates in her desires, Narraboth circles with a video camera - presumably for up-loading to YouTube - before killing himself. Slipping her feet into Jokanaan’s stilettos, Salome indulges in some necrophiliac writhing on the Syrian guard. She had unwound her clothing, to bare her flesh; now, Jokanaan unties the bandage on his wrist in order to shield his eyes from such debauchery.

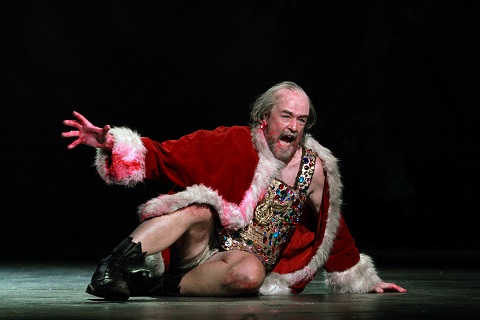

Michael Colvin (Herod). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Michael Colvin (Herod). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Leaving the prison to return to Herod’s ‘pleasure’ palace, we find the monarch frolicking with four nymphs in shiny nude leotards. Dressed in a be-jewelled wrestler’s suit, grubby boxer shorts and Santa coat, Michael Colvin is a ‘Mad King’ indeed. Desperate, debauched and deluded, he makes George III look a picture of mental and physical health. His ‘courtiers’ sit on the side-lines, aptly dressed in blue surgical gowns and gloves - they are going to have to do the clearing up, after all. Herod slithers in Narraboth’s blood; a rosy My Little Pony is decapitated, disembowelled and hoisted aloft, its mane hanging limply as its floral entrails spill across the stage. In the face of such dysfunctionality, the eloquent pleas of the Nazarenes (Robert Winslade Anderson and Adam Sullivan) are as impotent as the knock-kneed Herod. Herodias (Susan Bickley) wraps herself in a net-curtain which has been pulled down to reveal a blindfolded Saint Sebastian-cum-David Bowie.

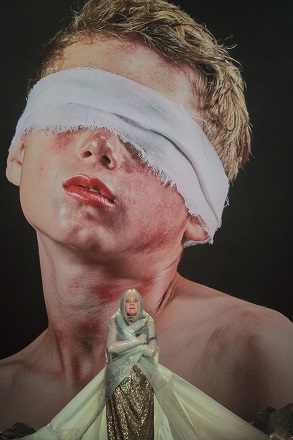

Susan Bickley (Herodias). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Susan Bickley (Herodias). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

I confess that, by this point, I was suffering from an overload of the absurd. I hoped that some sense of ‘purpose’ or context would arise from the Dance of the Seven Veil’s and Salome’s final monologue: the still points at which Salome is the focus of our own voyeurism. Allison Cook is a terrific singing-actor and she has all the notes in her arsenal, if not quite the gloss that might outshine the instrumental excess.

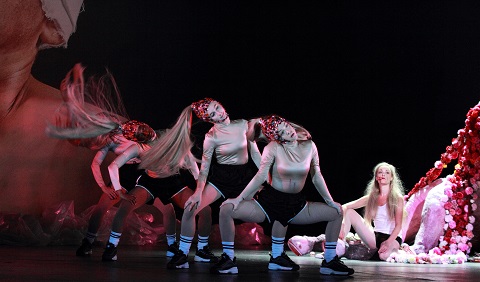

But, her Salome doesn’t so much as dance as pose languidly and grasp a baseball bat, appropriating phallic authority. Having discarded her Barbie-doll candy-pink sweatshirt and whipped off her blond wig to reveal a power-haircut, she slides up the pony’s belly and revels in its ripe intestines. Four dancers - Essex-scrapes, black football shorts, sequinned head-dresses - jerk and twerk.

Ensemble dancers and Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Ensemble dancers and Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Jacobs believes that the dance is not a ‘true unveiling or an expression of the soul. It is a dance constructed for Herod’s gaze … On this night, Salome subverts the dance for her own gain, she uses it to radicalise herself’. It is not mystical, she declares, but ‘an escalation of her power, a ritualistic dance for the head of Jokanaan, an act of ritual preparation.’ Well, the notion that women can subvert the patriarchal, scopophiliac gaze is nothing new; even Flaubert suggested that Salome usurped power, that her movements evaded male determination: ‘With her eyes half-closed she twisted her body backwards and forwards, making her belly rise and her breasts quiver, while her face remained expressionless and her feet never stopped moving … From her arms, her feet, and her clothes there shot out invisible fire.’ But, what if there is no ‘movement’: can her dance still empower? Though conductor Martyn Brabbins drew radiant silk and riotous sleaze from the ENO Orchestra, I was unable to make sense of the schism that opened between visual image and musical motion.

Having turned all male heads, Salome then topples them. And, it is the severed head - in Wilde’s play, this is a magisterial and monstrous Medusa - that ultimately draws our gaze. But, Jacobs doesn’t give us a head, only a lumpen white plastic bag. This makes a nonsense of the text and psychology of the monologue - ‘If you had looked at me, you would have loved me’, she sings to the severed gore, desperate to command Jokanaan’s gaze.

Allison Cook (Salome’s monologue). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Allison Cook (Salome’s monologue). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

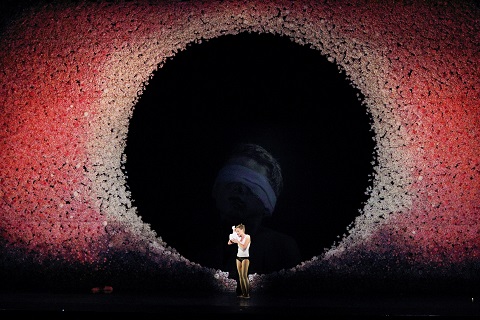

One thinks again of Pell’s portrait of Salome with its empty platter. Is this Jacobs’s design: if there is no head then our gaze remains fixed on Salome herself and thus the patriarchy does not re-exert its power? The director’s final image is equivocal: a flower-bordered black-hole, framing the bandage-eyed Bowie look-a-like; is this a mouth, a vulva, or what Elena Manafi (Senior Tutor/Programme Director PsychD In Psychotherapeutic and Counselling Psychology at the University of Surrey) describes in her programme article as ‘the abyss of the feminine’? Jacobs, it would appear, wants to turn Salome’s pathological narcissism into a ‘victory’, but her Salome is figuratively blinded by solipsism: and, spoiler alert, literally blinded by her mother’s hands which shroud her eyes from the truth that the lips she kisses are not Jokanaan’s - he’s still in the plastic bag - but Herodias’s own? Aren’t there enough Freudian threads in this tale already …

Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

Allison Cook (Salome). Photo Credit: Catherine Ashmore.

This Salome ends as the protagonist places a phallic gun in her mouth. Manafi argues that ‘Destruction becomes a form of liberation’, and that although Salome’s attempts to master and manipulate the male gaze have been ‘nothing but mimicry’ of patriarchal dynamics, her final act is an ‘outburst of violence that constitutes her emancipation’. But, Jacobs and Manafi seem to have forgotten that there is a theatrical audience: she becomes a prey to our gaze. As scholar Peter Conrad has observed, ‘Salome ceases to be a character and becomes an image, and opera turns simultaneously into a symphonic poem, into a ballet, and into a painting’. [2]

Jacobs allows for equivocation. But Angela Carter did just this nearly forty years ago, in the stories of The Bloody Chamber where the fantastical allows women to embrace their inner ‘darkness’: some critics argue that the female ‘victims’ of Carter’s fairy-tales become gradually empowered by embracing desire and passion as a human animal, others that Carter envisages women’s sensuality simply as a response to male arousal and that her tales can only reproduce patriarchal values rather than modify or shatter them.

Jacobs gives us arresting and intriguing visual images, but her Salome is smorgasbord of ideas and theories. Narraboth’s blood and the pony’s entrails are too slippery to tie the tableaux together.

Claire Seymour

Richard Strauss: Salome

Salome - Allison Cook, Jokanaan - David Soar, Herod - Michael Colvin, Herodias - Susan Bickley, Narraboth - Stuart Jackson, Nazarenes - Robert Winslade Anderson/Adam Sullivan, Herodias’s Page - Clare Presland, Soldiers - Simon Shibambu/Ronald Nairne, A Cappadocian - Trevor Eliot Bowes, Slave - Ceferina Penny, Jews - Daniel Norman/ Christopher Turner/Amar Muchhala/Alun Rhys-Jenkins/Jonathan Lemalu; Director - Adena Jacobs, Conductor - Martyn Brabbins, Designer - Marg Horwell, Lighting Designer - Lucy Carter, Choreographer - Melanie Lane, Orchestra of English National Opera.

English National Opera, Coliseum, London; Friday 28th September 2018.