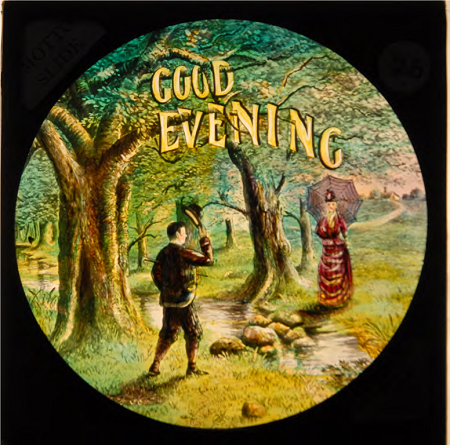

In 1668, the English scientist Robert Hooke published an article in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, in

which he described the projection of transparent and opaque objects,

illuminated by sunlight or candle. Two years earlier, and two weeks before

the Fire of London, Samuel Pepys had purchased a lantern from the London

optician John Reeves recording in his diary, “Comes by agreement Mr Reeves,

bringing me a lanthorn, with pictures on glass, to make strange things

appear on a wall, very pretty”. Camera obscuras, magic mirrors, Laterna

Magica, Phantasmagoria; for millennia, people have been enchanting,

terrifying and transfixing each other with projected lights and shadows,

shapes and colours, spinning tales of wonder and terror.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad’s forthcoming new recording, Magic Lantern Tales, similarly presents us a veritable son et lumière of musical light, colour, shapes and sounds. The

cycle which gives the disc its title presents five poems from Ian

McMillan’s collection Magic Lantern Tales (2014), written in

response to interviews and documentary photographs by Ian Beesley. In 1994,

Beesley was appointed artist-in-residence at the Moor Psychiatric Hospital

in Lancaster, working on the unit specifically for the care of the extreme

elderly, many of whom had been in the Moor for decades. H discovered a

collection of old photographs in a chest of drawers, many of which were

related to the First World War - soldiers in uniform, family gatherings,

and weddings with the grooms in uniform - which had belonged to patients

who had died in the hospital and who had no living relatives. Beesley

describes these fading photographs as ‘a visual eulogy to forgotten lives’;

they prompted him “to photograph and interview as many men and women who

had experienced the First World War before it was too late”.

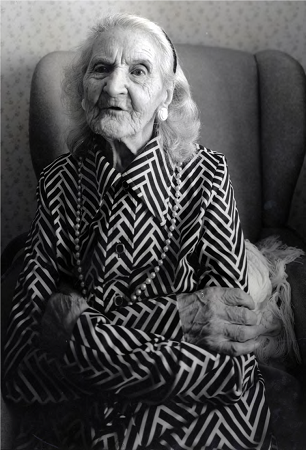

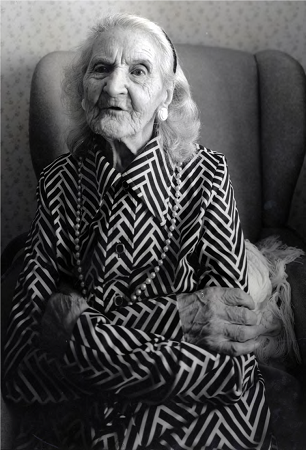

Lily Maynard. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

Lily Maynard. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

He and McMillan subsequently created a magic lantern show to present these

personal narratives of the War by those who survived it. Now, Frances-Hoad

has given musical expression to the stories of Lily Maynard (101), who told

Beesley of her grief for her beloved, “We were thinking of getting married,

when he went off to France , the Somme”; Harry Holmes (100), who was

decorated for his bravery at Ypres when, whilst trying to retrieve wounded

colleagues from no-man’s-land, he single-handedly captured five German

soldiers; and Mabel Walsh (104), whose fiancé was killed in 1918 when

struck in the head by a small piece of shrapnel, and who, like Lily, never

married.

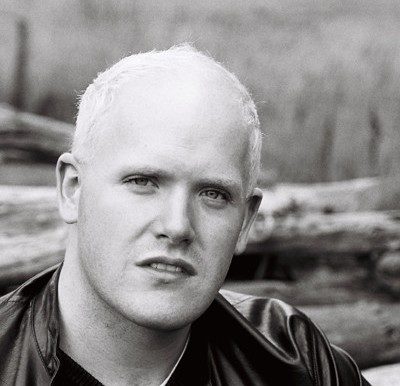

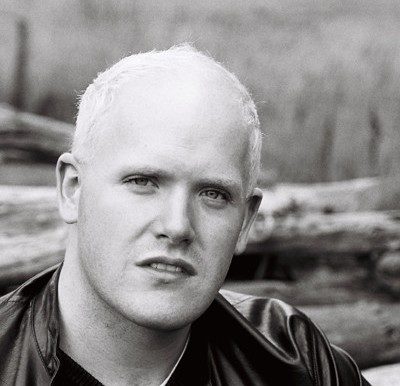

Nicky Spence. Photo Credit: Mardo Studio.

Nicky Spence. Photo Credit: Mardo Studio.

Frances-Hoad frames their memories with McMillan’s ‘Marching Through Time’,

and so the cycle opens with a quiet but purposeful tolling, as pianist

Sholto Kynoch summons Nicky Spence’s folk-tinged preface to the subsequent

unfolding of the past, drawing the voice back to its anchor just as

dissonant second and ninths reveal the narrator’s wish for release. Just

over three minutes long, this is a marvellously crafted song which, through

the expanding bare fifths and octaves in the accompaniment, the rhythmic

and resonant intimation of military echoes, and the tense heightening of

the vocal line, travels widely through time, place and emotions. The

ascending line, “Stories rebuild just what wartime destroys”, spills

intensely into a densely accompanied proclamation: “And a photograph is a

kind of map.” Spence’s unaccompanied voice bursts with the anguished weight

of memory, “That story lifting up the tentflap of history”. There is a

subtle chromatic alteration in the repeated final line, “Stories as brittle

as glass”, to which Spence adds timbral nuance, which is both beautiful and

anguished. Such precise musical insight into the relationship between

sound, sense and sensibility is characteristic of Frances-Hoad’s writing in

all of the compositions recorded on this disc, and the results are deeply

affecting.

The piano introduction to ‘Lily Maynard’ swings with a lovely lop-sided

lilt, which is complemented by Spence’s warm, affectionate tone in the

refrain, “Come on Lily, Let’s go walking”, and as the song and journey into

memory proceed, so the enrichening of the piano’s harmony expresses first a

sensuous passion, “Heating up the air something magical”, and then a pained

portentousness, “And you pictured him in a trench/ Cowering and crying like

a baby.” Spence’s repetitions of Lily’s name somehow seems both encouraging

and tormenting, but the softness of the tenor’s head voice in the final

refrain, “We’ll talk as we’re walking/ And pretend you’re young again,/

Lily”, follows Kynoch’s star-bound accompaniment into the air and we too

are borne aloft on Lily’s dreams and memories.

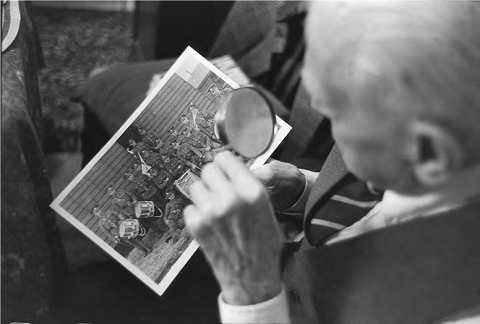

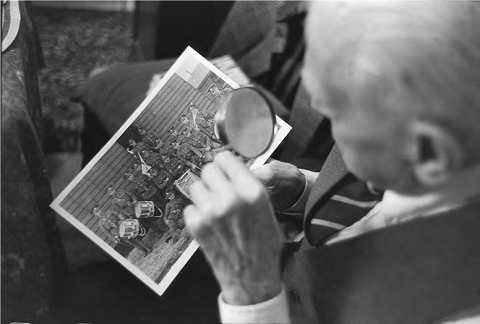

Harry Holmes. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

Harry Holmes. Photo Credit: Ian Beesley.

‘The Ballad of Harry Holmes’, like ‘Lily Maynard’, evokes a war-time song,

but now wistfulness is replaced by chirpy resilience, as Spence’s narrator

launches with rollicking gusto into this tale of brave Harry who meets

bombs, barbed wire and a bonfire-sky with the pragmatic refrain: “All O

want when I get through this,/Is a stroll, and a pint, and a kiss.” The

rattling spikiness and quirkiness of the piano’s ringing tattoo - which

reappears in various guises through the tale - brings Britten to mind, as

does the text-setting. Spence’s expansive, galloping laudation, “I guess

Harry was a hero”, is halted by the half-spoken whisper, “don’t take me…”,

uttered in the “stinking night” to the dark terror. Frances-Hoad whips us

through an extraordinary panoply of fluctuation moods and emotions. A

cockney voice yelps with joy, “Harry, it’s over!”; the perennial bird-song

stills the bombs; Harry’s chest puffs with pride on his home streets of

Bradford; Harry-the-decorator dismisses his Military Cross in Yorkshire

brogue, “a medal’s just a gaudy lump of tin”; he and Harry Ramsden of

chip-shop fame hatch plots to frequent the Crown Inn when Harry R’s wife

objects to his ale glugging. Frances-Hoad paints vivid pictures of Harry’s

life and at the close, when Spence reflects, “Now Harry’s tale has been

told”, we feel that we’ve travelled with him through his adventures and

that we know him well, and love him.

The rhythmic ambiguities of the destabilising piano ‘clock-ticking’ in

‘Mabel Walsh’ suggest the centenarian’s straddling and merging of past and

present. The effect is heightened by the piano’s gentle inter-verse

ringing, a motif which is drily reiterated at the close as we hear “the

hourly chimes/ Struck silent by that bastard war”.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad.

Cheryl Frances-Hoad.

There is more magic and memory, as well as strong characters and strange

places, in the other substantial ‘cycle’ included on the disc: The Thought Machine, ten settings of poems from Kate Wakeling’s

children’s collection, Moon Juice (2016), which was commissioned

by the Oxford Lieder Festival. Frances-Hoad’s delight in the whimsical and

wry is ever-present in these songs, as is her feeling for the

sophistication of a child’s perspective and assimilation of the ‘weirdness

of the world’. We are sucked into an echoing cosmic vastness by the piano’s

low shudderings and high tremors in ‘Telescope’, and by the slow

intertwining, intoning and swooping of the two vocal lines, expertly

pitched and co-ordinated by Sophie Daneman and baritone Mark Stone. We

glide along the “dizzy black” motorway in ‘Night Journey’, Kynoch’s

accompaniment a swirling kaleidoscope of colours and lights that form

fantastic shapes in Daneman’s imagination. The singers bring Skig the

Warrior and Rita the Pirate to vibrant life - the former more coward than

combatant, the latter a swashbuckling gold-grabber who pinches your money

with panache, to the tune of a Paganini caprice. The Hamster Man runs round

and round his wheel in a wild fury; The light-fingered Thief is cheekily

brazen - he even filches the last word of the song. Daneman gleams and

teases with mystery in ‘Moon’, with the singers race impressively through

the tongue-twisting text of ‘Comet’. After we’ve been pounded, spun and

‘shaken’ in ‘Machine’, bell-chimes send us in search of the ‘Shadow Boy’ as

Stone and Daneman smoothly and assuredly traverse the wide-spanning vocal

lines, reaching higher and higher as the tentative child tries his hardest

to brave the dark.

Sophie Daneman. Photo Credit: Sandra Lousada.

Sophie Daneman. Photo Credit: Sandra Lousada.

There are childhood experiences of a different kind in ‘Scenes from

Autistic Bedtime’ which have their origins in a workshop for a projected

chamber opera. The text was written by Stuart Murray, Professor of

Comparative Literature at the University of Leeds and author of Representing Autism (2008), and the three scenes share the opening

line, “It is shower time. It is bedtime”, as well as a continuous,

shape-shifting piano accompaniment of splashes, splutterings and

stutterings, played by Alisdair Hogarth. Treble Edward Nieland sings the

child’s short phrases with a directness and clarity that is at first at

little unnerving against the unstable piano accompaniment, but we hear too

his mother’s voice (Natalie Raybould), by turns anxious then weary,

relieved then resigned, but always loving. And, in the second scene she

joins her child’s shower-song, in which the soaring voices, warmly lyrical

cello (Anna Menzies) and glorious vibraphone chiming (Beth Higham-Edwards)

grow into a glowing, intense expression of creativity, joy and laughter.

There is darkness and confusion, even the threat of violence, in the third

section, but if these scenes are disorientating at times, they are also

uplifting and communicate with a striking strength that is both emotive and

visceral.

Sholto Kynoch. Photo Credit: Raphaelle Photography.

Sholto Kynoch. Photo Credit: Raphaelle Photography.

Frances-Hoad also conjures ‘alternative perspectives’ in Love Bytes: A Virtual Romance, in which ‘he’ (the cello) and ‘she’

(the vibraphone) articulate and enhance the strange conversation between

two cyber-lovers, baritone Philip Smith and soprano Verity Wingate, who

wonder just who exactly is on the end of the digital ‘line’. Frances-Hoad

treads the fine line between a Walton-esque flippancy and the fragility of

human connection and alienation; and, there is both wit and poignancy in

their concluding reflection, “Perhaps it’s best/ We never meet at all”. Lament, an affecting setting of a text by Sir Andrew Motion, is

sung with vivid emotional presence by mezzo-soprano Anna Huntley,

accompanied by Hogarth. Hogarth also performs Invoke Now the Angels, conceived as a response to Britten’s

Canticles I and II, which brings Wingate together with mezzo-soprano Sinéad

O’Kelly and countertenor Collin Shay. This trio sing the a cappella A Song Incomplete, which sets text by Aristotle; Kynoch performs

two short piano works, Star Falling and Blurry Bagatelle.

The works on this disc are varied in tone, context and form, but they are

also consistent in the very visceral effects that they have upon the

listener. Frances-Hoad’s Magic Lantern Tales disorientate and

delight in equal measure.

Magic Lantern Tales is released on the Champs Hill label in

November 2018.

Claire Seymour