Not a bad 10th birthday present for the House, which opened in

2008 and was designated Ireland’s

National Opera House

in 2014, and one which this year’s Festival confirmed is greatly deserved.

Opening night offered a double dose of verismo viciousness and violence: a

compelling alternative to Cav & Pag. Born in 1864, Leoni

studied alongside Puccini and Mascagni at the Milan Conservatoire under the

supervision of Amilcare Ponchielli and Cesare Dominicetti. When he

emigrated in London in 1892, aged 28, Londoners took the Milanese composer

of operas, sacred works and ballads to their hearts. “Signor Leoni,

although a foreigner, has … proved himself a better friend to the cause of

English music than most people seem inclined to admit,” wrote ‘G.H.C.’ in

the Observer on 7th November 1909, and his view seems

to have been shared by many, if contemporary newspaper reports and letter

pages are anything to go by.

Correspondents praised Leoni’s instigation of the foundation of the Queen’s

Hall Choral Society, of which he became conductor, and admired his

endeavours “to inspire his chorus with a genial, warm Southern enthusiasm

[…] the general effect produced is keen and musicianly in the best sense of

the word”. After a performance of Leoni’s oratorio Golgotha at the

Queen’s Hall in 1911 one enthusiast, James Bernard Fagan, expressed the

somewhat florid opinion that “Mr Leoni has done for sacred music what

Francis of Assisi did for Christianity, bidding us look for the spirit of

God not in cold, gloomy, formless abstractions on remote unscalable

heights, but down on the warm earth - in trees and in flowers and in

running waters, in the birds and in the beasts, and in the hearts of men”.

There’s not much evidence of “the spirit of God” in L’oracolo ( The Oracle) which premiered at Covent Garden on 28th

June 1905, conducted by André Messager and with Antonio Scotti playing the

vicious and venal Cim-Fen. Set in an opium den in San Francisco’s

Chinatown, Camille Zanoni’s libretto - based on a Chinese-American story, The Cat and the Cherub, by Chester Bailey Fernald - is swift and

sensational. It crams villainy and viciousness, kidnapping and stabbing,

strangulation and insanity into its sixty minutes. Its personnel include

gamblers and fortune-tellers, drug addicts and reprobates, as well as

chattering choruses of children and vendors. The action takes us through

the seedy back-streets of 1900 Chinatown, down alley-ways which are choked

by the San Francisco fog and the festering stench of the running drains,

and teaming with caterwauling costermongers. The opium dens of ‘Hatchet

Row’ are ruled by Cim-Fen, a merciless cut-throat who wields his knife with

slickness and a smile.

Leon Kim and Joo Won Kang. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Leon Kim and Joo Won Kang. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

The eponymous Oracle predicts that two people will die, and murder follows

murder with chilling speed and inevitability. When San-Lui discovers that

Cim-Fen has kidnapped the child of the wealthy merchant Hu-Tsin - in a ploy

to win the hand of Hu-Tsin’s niece, Ah-Joe, by heroically ‘rescuing’ the

infant - Cim-Fen despatches his love rival with an efficient single

hatchet-blow to the back of the head. Uin-San-Lui’s father, Uin-Scî, may be

of philosophical bent, but that doesn’t stop him displaying his own

thuggish resourcefulness and expertise in seeking vengeance. When the blade

that he has plunged into Cim-Fen’s back fails in its fatal intent, Uin-Scî

calmly winds his son’s killer’s plait around his neck and with delicate

deliberation proceeds to strangle him. So peacefully occupied in quiet

conversation do the pair appear, seated side-by-side on a bench, that a

passing policemen notices nothing amiss.

Director Rodula Gaitanou and designer Cordelia Chisholm leave us in no

doubt of the squalor and sadism of life in the ghetto. Dimly lit by Paul

Hackenmueller, Chisholm’s set is dominated by a towering, three-story brick

edifice which revolves to reveal the business premises of Dr Uin-Scî, a

Chinese herbalist, the imposing entrance to the domestic quarters of

Hu-Tsin, and the red-lit steps which descend into the bowels of Cim-Fen’s

opium den. We are swirled along with the chattering Chinese inhabitants

through the network of grimy alleyways. A corner street-light illuminates

the coarseness and brutality of the gamblers, drug-takers and drinkers

departing Cim-Fen’s den: knives flash in the lamp-light gloom, fists lash

out, grievances are born and nurtured. Even the festive spectacle of a

Chinese New Year Dragon Procession doesn’t alleviate the shabby sleaziness:

the festooning red balloons can’t hide the shabbiness of the parading

wagons, and the arching Dragon dips and dives menacingly, glaring with a

mean, sharp-toothed stare.

Much of the success of L’oracolo was due to Scotti’s championing

of the opera at the Met, where he persuaded General Manager Giulio

Gatti-Casazza to present the work in 1915. It became a star vehicle for

Scotti - often paired with Cavalleria Rusticana, Pagliacci, L’Amico Fritz and even La boh ème - until 1933, when the 55th performance of the

opera served as the Italian baritone’s farewell to the house. Here, Joo Won

Kang was entrusted with embodying the repugnant Cim-Fen, and his baritone

was darkly aggressive at the bottom, richly coloured in the middle and firm

of weight throughout. As Uin-San-Lui, Sergio Escobar provided complementary

lightness and beauty, his tenor ringing brightly at the top, though there

was little chemistry between Escobar and Elisabetta Farris’s Ah-Joe. But,

if their voices didn’t blend with sufficiently powerful rhapsodic intimacy

in the duet which is ended by Cim-Fen’s plunging knife, then the gentle

beauty of Farris’s soprano did win our pity for the suffering girl, though

Gaitanou did little to suggest that Ah-Joe’s grief was followed by mental

derangement.

Sergio Escobar and Elisabetta Farris. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Sergio Escobar and Elisabetta Farris. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Leon Kim was superb as Uin-Scî, his grave and authoritative manner never

concealing the sincerity of his love or integrity of his belief: the

bereaved father’s appeal to the ‘Supreme Divinity of the Western Sky’ to

reveal his son’s assassin was both chilling in its implications and

compelling in its genuinely human motivation. The role of Hu-Tsin was

commandingly sung by Benjamin Cho, while Louise Innes acted and sang

convincingly as Hua-Quî, nurse to the kidnapped Hu-Cî. The latter was

portrayed with infectious spiritedness by Cillian McCamley, who yawned

cheekily during the adults’ rituals and sprinted around mischievously

before he was imprisoned by Cim-Fen, first a garbage bin, then down the

coal chute.

Conductor Francesco Cilluffo - who led

Mascagni’s Isabeau

impressively at Opera Holland Park this summer - had the measure of the

score’s melodrama and pace, finding both stirring passion and moments of

lightness, and the Orchestra of Wexford Festival Opera painted the diverse

local colours with vividness and energy. There was especially fine playing

from the lower strings, particularly during Uin-Scî’s retributive prayer

and vow.

Despite the unalleviated ruthlessness and savagery which Leoni and Zanoni

dish up, Gaitanou obviously felt there was room for more. Leon Kim’s

Chinese herbalist did not consider throttling-by-pigtail to be sufficient

punishment for his son’s murderer: instead, he exercised a ritual

disembowelment of the barely-breathing Cim-Fen, slicing through clothes,

peeling back skin and plunging his hand into the cut-throat criminal’s

chest - should we have been in doubt, by the close the latter really was

‘heartless’. And, though the libretto ends with Uin-Scî’s vengeful actions

undiscovered, here the clinical killer immediately confessed his crime to

the passing policeman, crossing his wrists to indicate that the cuff-links

should be clicked into place. The result was not the resumption of ‘normal’

life with which the original concludes, but the unbalancing of the scales

of justice.

After the interval, Chisholm’s set was deftly transformed - out with the

herbalist and in with Valentino’s cobbler’s shop, the Bella Napoli

café replacing the opium den, and laden washing-lines adding to the

authenticity of the milieu in the second Act - in order to transfer us from

San Francisco’s Chinatown at the turn of the century to New York’s Little

Italy in the 1950s. There are no knifings or strangulations in Umberto

Giordano’s Mala vita but, like L’oracolo, for a

relatively small-scale drama the large-scale musical climaxes pull no

emotional punches and hit the theatrical bull’s-eye. Librettist Nicola

Daspuro’s lurid tale of Neapolitan low-life - based on a play by Salvatore

Di Giacomo and Goffredo Cognetti, which was itself derived from Giacomo’s

1888 short story Il voto (The vow) - was a success at its premiere

in Rome’s Teatro Argentina in February 1892, and also surprisingly

well-received when, translated into German, it was subsequently presented

in Germany and Austria. But, Mala vita didn’t go down so well with

the Neapolitans, who were less appreciative of Giordano’s ‘veristic’ - in

their eyes, insulting - depiction of the ‘wretched lives’ endured in

Naples’ ugly alleyways and slum dwellings.

The opera takes us into what Matilde Serao, the author of Il ventre di Napoli (1884), described as ‘the bowels of Naples’.

Vito, who works in a dye-house, believes that the tuberculosis that

afflicts him, rather than being an inevitable consequent of the chemicals

and fumes he ingests each day, is a punishment from God for his

misdemeanours - including his affair with Amalia, of which only her

coachman husband Annetiello seems unaware. In hope of a cure and divine

forgiveness, Vito vows to give up Amalia and marry a prostitute, thereby

saving the fallen woman from a life of degradation and his own soul from

damnation. News of his vow travels fast through the slum alleyways and when

Cristina drops a rose from her brothel window onto the passing Vito’s

shoulders, she is chosen as his path to redemption - to the brothel-regular

Annetiello’s amusement and Amalia’s anger. The latter confronts Cristina,

and Vito, unable to resist Amalia’s wiles and charms, ditches Cristina

along with his plans for physical and moral improvement, leaving Cristina

to lament that Jesus obviously didn’t want her to be redeemed after all.

Chorus of Mala vita. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Chorus of Mala vita. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

The expansive anguished and impassioned outbursts of the three protagonists

stand out against the musical ‘backdrop’ provided by Giordano of everyday

neighbourhood goings-on, and the Wexford Festival Chorus sang, and danced,

with real spirit and vivacity. Gaitanou blocked the ensemble scenes more

successfully than in L’oracolo, where occasionally the narrow

street-strip at the front of the stage seemed crowded and the Dragon

procession felt less than fluid. In contrast, the traditional Piedigrotta procession and festivities were vividly animated: the

tarantella sprang ebulliently as the Neapolitan folk songs rang out

colourfully, the snaking lines of revellers intertwined dexterously, and

the children practised their dance-steps at the side of the stage.

Similarly, the Chorus captured the intensity of the community’s belief in

popular local superstitions during the opening vow scene.

Sergio Escobar and Chorus. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Sergio Escobar and Chorus. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Escobar was able to tap all the warm lyricism of his tenor and did his best

to make Vito’s lurches from fervent prayer to ardent romance convincing, as

he switched from devout consumptive to devious charmer in the blink of an

eye. The characterisation is largely conveyed through the three main duets

which bring Vito and Cristina together in Act 1, Amalia and Cristina into

confrontation in Act 2 and subsequently reunite Amalia and Vito, and

Escobar was well-partnered by both Dorothea Spilger’s Amalia and Francesca

Tiburzi’s Cristina. Spilger was a powerful presence especially in Act 2,

which Amalia dominates, communicating all of Amalia’s selfishness,

recklessness and wilfulness. Her mezzo-soprano is powerful and focused, and

in the lunchtime recital which she gave the following day, in St Iberius’s

Church, she revealed its full range of colour, vibrancy and intensity, the

dense layers of the bottom being complemented by strikingly intense and

pure top notes. Spilger moved effortlessly between high and low, too, and

her presentation of songs by Brahms, Schumann and Richard Strauss, and an

aria from Lehár’s Zigeunerliebe, confirmed her flawless technique

and assurance, and dramatic range.

Dorothea Spilger and Francesca Tiburzi. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Dorothea Spilger and Francesca Tiburzi. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

In Mala vita, however, it was Tiburzi’s Cristina who

almost stole the show with her Act 3 prayer, in which the sensuous richness

of her mezzo suggested, ironically, that her real passion and fervour was

reserved for the spiritual rather than the earthly. Tiburzi had terrific

rapport with Escobar’s Vito, and in their Act 1 duet the lucidity and

elegance of line evoked the tenderness of a Puccinian melody. Annetiello is

a rather limited role (when Giordano revised the opera and represented it

as Il voto (The vow) in 1897, he omitted the character)

though Leon Kim made the most of it, relaxing his baritone to suggest a

good-time-lad preoccupied with the pleasures in life. He joyfully

anticipated the hedonistic excesses of the festival to come, as he prepared

his horses’ harnesses and plumes, and joined his mates in a rousing

brindisi in Act 3. Benjamin Cho and Anna Jeffers provide good support in

the roles of Marco and Nunzia respectively.

Cilluffo again conducted with conviction, driving the orchestra to emotive

act closures and summoning a rich palette during the Intermezzo in Act 2

which provides some musical pathetic fallacy during the storm, while also

creating moments of intimacy through some excellent quiet string passages.

Gaitanou once again exercised directorial license with the ending. In the

libretto, as Cristina ends her prayer, the folk song which Annetiello has

sung during the festivities is heard again, reminisced by the off-stage

chorus, suggesting that while Cristina suffers alone the indifferent

community continue their Piedigrotta revels. The sound of the song

rouses Cristina who cries contemptuously, “Infami! Vili! Ah!”, before

rushing back towards the door of the brothel. Gaitanou clearly can’t

envisage Cristina resuming her former employment, so she has the prostitute

put a gun to her head and pull the trigger. Giordano, like Leoni, takes the

action back to where it started: no moral judgements are made, this is

simply how these people live their lives. I would have preferred this

‘slice of life’ plain, without any aesthetic air-brushing.

Indeed, ‘endings’ proved rather problematic at Wexford this year! So

composer William Bolcom and librettist Mark Campbell explained during their

‘Meet the Creators’ talk, the morning following the European premiere of Dinner at Eight, a co-production with Minnesota Opera where the

opera was first seen in March 2017. Campbell’s libretto offers a very

different ‘slice of life’. Based on George S. Kaufman and Edna Ferber’s

1932 play, Dinner at Eight is a black comedy which pillories and

pities the desperate efforts of a bunch of nervy New York socialites to

keep up appearances as the miseries of the Depression, and their own

foibles and moral weaknesses, threaten to bring their paper-thin social

edifices tumbling down.

During the week preceding Millicent Jordan’s eponymous dinner, the hostess

frets about the fate of the gastronomic centrepiece as the lobster-in-aspic

nose-dives to the kitchen floor; wails about the lone Hungarian viola

player who replaces the planned string quartet; and hysterically laments

the non-show of her prime exhibits, Lord and Lady Ferncliffe, who forgo her

hospitality for the sunshine of Florida. Meanwhile, her guests struggle

with rather more significant worries and reveal their instabilities,

insecurities and immoralities. Oliver Jordan’s fragile grip on his shipping

line company is being loosened by former actress Carlotta Vance’s need to

sell her stock to avoid insolvency, and by the treacherous double-dealing

of Dan Packard, a capitalist with political aspirations that his wife

Kitty, who is having an affair with her doctor, Joseph Talbot, threatens to

undermine. The Jordans’ daughter Paula wants to ditch her boring fiancé for

the charms of former matinée idol Larry Renault, an aging has-been whose

alcoholism has ravaged the good looks that were his only asset, and who has

just been dropped from the cast of his latest Broadway play.

Susannah Billar and Brett Polegato. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Susannah Billar and Brett Polegato. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Set designer Alexander Dodge has supplied beautiful milieus for Tomer

Zvulun’s production, and the sleek art deco elegance is charmingly

complemented by Victoria Tzykun’s costumes and boldly lit by Robert

Wierzel. The set is framed by a monochrome topographic jigsaw of

Manhattan’s monuments - think Escher meets Google Satellite - and screened

snippets of the Depression era nod towards the drama’s cinematic past

(George Cukor’s 1933 film adaptation included John Barrymore, Jean Harlow,

Marie Dressler, Lionel Barrymore and Lee Tracey, among others, in its

ensemble cast). Time and place are well-defined: as Bolcom explained, the

play was designed for a ‘local’ audience whereas the film had appealed to a

broader set of ‘national’ viewers. The clean, cream splendour of the

Jordans’ sparkling chandeliers and tortoise-shell inlays is juxtaposed with

the tasteless trappings of the Packards’ gaudy, glitzy bedroom where Kitty

reclines on the king-size bed, scoffing chocolates from a heart-shaped box

and admiring her jewellery as she awaits the next dose of the doctor’s

‘medicine’. We see inside the clinical offices of Oliver Jordan and Dr

Joseph Talbot, the walls sporting photographs of cruise liners and

cross-sections of the human brain respectively, and witness Paula’s efforts

to convince Larry to elope in the charmless hotel room from which the

penniless thespian will shortly be evicted when the management’s patience

runs out.

Bolcom’s score is a skilful medley of varied pastiches, played by a

Broadway-tinted band that can swell with symphonic sumptuousness

in-between-scenes, and withdraw to sensitively support the aria-numbers

allotted to each of the struggling protagonists. There are some fine

woodwind colourings, toe-tapping rhythms, and lush climaxes, but while

slick, the score isn’t very memorable.

Richard Cox. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Richard Cox. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Several of the cast were reprising their roles from the original Minnesota

Opera production. Stephen Powell’s warm baritone made Oliver Jordan’s

vacillations between honest self-appraisal and the need to sustain

Millicent’s delusions and desires real and engaging, and Oliver’s nostalgic

duet with Brenda Harris’s larger-than-life but down-on-her-luck Carlotta

Vance was one of the musical highlights. Craig Irvin boldly captured Dan

Packard’s self-important, arrogant swagger. Susannah Biller’s gold-digging

doll, Kitty, was a perfect picture of frothy, pink-swathed self-indulgence;

it was hard to suppress a smile when Kitty’s maid, Tina, brightly sung by

Laura Margaret Smith, resorted to subtle threats of blackmail to wheedle a

diamante bracelet from her mistress. Sharon Carty impressed as Lucy Talbot,

skewering her philandering husband’s weaknesses in a strong, purposeful

aria of unflinching honesty, while Richard Cox conveyed all of Larry’s

despair, frustration and anger in a powerful, bitter aria of failure and

regret. Gemma Summerfield made much of Paula’s Act 1 lament about Larry’s

wavering and her romantic woes. Presiding overall all with assurance, gloss

and gleam was American soprano Mary Dunleavy’s Millicent - buoyant,

resourceful, and, despite her histrionic excesses, resilient to the last.

Bolcom’s Sondheim-style idiom is easy on the ear, but the score does not

itself have a ‘dramatic’ function. The following morning, Bolcom and

Campbell described Dinner at Eight as musical theatre sung by

opera singers: I’d go further and say that the music functions like a film

score, colouring and joining the scenes but not itself explicating the

characters’ motivations, actions and conflicts. Wexford’s Artistic Director

David Agler, who conducted the opera in Minnesota and led a slick and neat

performance here, has brought several American operas to Wexford during his

very successful tenure. I very much admired Carlisle Floyd’s Susannah, which formed part of Agler’s first festival programme in

2005, as well as John Corigliano’s

The Ghosts of Versailles

(presented in 2009), and Samuel Barber’s

Vanessa

(in 2016); but, I was less enamoured by Peter Ash’s

The Golden Ticket

(in 2010) or by Kevin Puts’

Silent Night

(in 2014). On this occasion, whatever my own misgivings, it’s fair to say

that during the first performance of Dinner at Eight the Wexford

clientele seemed absorbed and engaged.

And, so, what of the ‘ending’ that I mentioned above? A rhymed chorus gets

the show underway, as the servants line up to inform us, with insouciant

indifference to the impending tragedies, that “The party goes on, like it

or not”. And, so it does: despite all the heartache and imminent doom, the

gong sounds at eight o’clock and the guests take their places at the dinner

table. Oliver’s luxury liners are about to sink as fast as his company’s

share price, and he himself will succumb in three months to terminal heart

disease, according to Dr Talbot’s grim diagnosis. Larry has committed

suicide in his hotel room, by leaving the gas taps on, artfully arranging

himself in a chair in one last theatrical pose. Marriages, careers and

finances are floundering.

Stephen Powell and Gemma Summerfield. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Stephen Powell and Gemma Summerfield. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

But, the Jordans vow that together they can survive both the evening’s

trials and any downturns or upsets that the future brings. And, that’s

that: curtain. It’s so inconclusive that the Wexford audience weren’t sure

if the opera had actually finished. Act 1 builds towards Millicent’s

spectacular hissy fit, and perhaps things should end there, as Act 2 has

little further to add. Or, perhaps the opera needs an Act 3, so that we can

find out what happens as the guests tuck into the spring lamb that the

caterers have delivered to replace the ill-fated crustacean? Whatever, the

current ending - which, we were told, the creators reworked when their

original idea proved unsatisfactory - leaves us teetering on a cliff-edge

then simply steps over the abyss and cheerily sweeps the brittleness aside.

Are we to presume that the dinner party goes smoothly and with a swing, to

the tuneful backdrop of a Hungarian czardas?

If there were unanswered questions at the close of Dinner at Eight

, then the plot of Saverio Mercadante’s Il bravo (1839)

proved unfathomable from the start, with the answers to some of the

libretto’s mysteries supplied only in the closing scene. Fortunately,

before these long-awaited revelations we had enjoyed three hours of

terrific singing and playing; I felt veritably swept along on the crest of

a grandiose musical wave of Verdian colour and energy.

Born in 1795, Mercadante was a significant figure in the world of

nineteenth-century Italian opera. During a career which overlapped with

Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi he composed sixty operas, and was

for thirty years (1840-1870) the director of the Conservatoire in Naples.

Wexford has previously shown faith in Mercadante, staging five of his

operas: Elisa e Claudio (1988), Elena da Feltre (1997), Il giuramento (2002), La vestale (2004) and

Virginia

(2010).

Il bravo

certainly confirmed the merits of Wexford’s conviction, though to say that

the plot is confused, and confusing, is something of an understatement.

Part of the problem is that too many pens have spoiled the plotting:

Antonio Bindocci, Gaetano Rossi, Marco Marcelliano Marcello, and Felice

Romani all worked on the libretto, which is based on the novel by James

Fenimore Cooper by way of Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois’s playLa Venitienne. Set in sixteenth-century Venice, the action begins in media res and without knowledge of prior events and the

historical background it’s virtually impossible to discern or make sense of

the characters’ motivations and relationships.

Yasko Sato and Ekaterina Bakanova. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Yasko Sato and Ekaterina Bakanova. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

The characters assume multiple disguises and several names: Pisani, who

loves Violetta, sports the Bravo’s mask and dagger for much of the opera;

the Bravo himself dresses as a Dalmatian nobleman. The protagonists don’t

even recognise each other: it’s only at the end that the Bravo (real name,

Carlo Ansaldi), and Teodora (formerly known as Violetta) realise that they

are in fact husband and wife - Carlo, who had stabbed Violetta when he

suspected her of infidelity, had not killed her after all, and the younger

Violetta, whom he had ‘adopted’ in order to protect her from the dastardly

Foscari’s plans to abduct her, genuinely is his daughter.

The drama is driven by the Bravo’s obligation to act as the Council of

Ten’s assassin, in order that his father (jailed along with the Bravo for

suspected treason) might be spared the death penalty: but, in the closing

moments we learn that he has died in jail, so the pact, and its dreadful

consequences proves to have been pointless.

The blue mists that swirled across the Wexford stage at the start of Renaud

Doucet’s production certainly seemed - along with set designer André

Barbe’s sharply angled perspectives of a Venice whose piazzas and waterways

are glimpsed through the narrow openings of up-turned palaces - an apt

metaphor for the plot’s obscurities. But, Doucet and Barbe muddy the canal

waters still further by introducing a troupe of twenty-first-century

tourists, trailing suitcases and taking selfies, who wander in anoraks and

sneakers amid the patrician Venetians attired in gloriously elaborate

sixteenth-century costume. Peering at maps and mobiles, they are apparently

just as ‘lost’ as we are - and, I decided, best ignored.

Rubens Pelizzari and Alessandro Luciano Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Rubens Pelizzari and Alessandro Luciano Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Indeed, it was easy to push the interlopers to the margins with such

terrific singing to distract one’s attention. In the title role, Rubens

Pelizzari gave a noble performance, attacking the lines cleanly with his

robust tenor. This was a convincing dramatic performance: when, in Act 1,

the Bravo returned to his home, divested himself of his mask and sang of

his sadness, the murdering henchman seemed less like Sparafucile and more

reminiscent of the tortured Rigoletto. In the second tenor role, Alessandro

Luciano was less strong as Pisani but he climbed easily enough to the top

and his phrasing was elegant.

Gustavo Castillo. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Gustavo Castillo. Photo Credit: Clive Barda.

Baritone Gustavo Castillo was a fittingly menacing Foscari and agilely

negotiated his cabaletta in Act 1. Yasko Sato seemed a little

tentative at first, but her Teodora grew in stature and the Act 3 duet for

mother and daughter was the expressive peak of the performance. Ekaterina

Bakanova’s richly coloured soprano was just right for Violetta’s intensity

and integrity. Conductor Jonathan Brandani whipped up musical storms and

strife in the pit, drawing great energy from Mercadante’s striking

harmonies and rich instrumental colours, but he also respected Mercadante’s

more innovative and translucent orchestrations. All in all, the dramatic

muddle was more than outweighed by the splendid musical drama.

Cast of Don Pasquale. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Cast of Don Pasquale. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

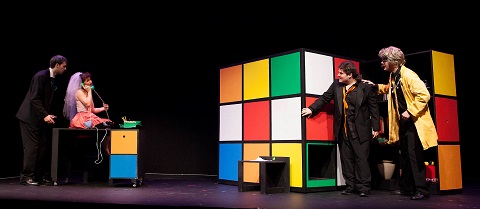

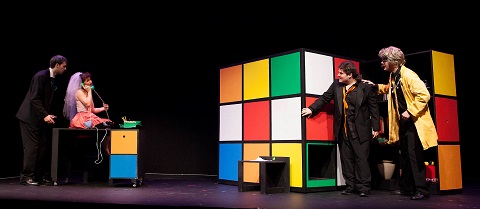

Alongside the three main productions, Wexford offered its customary three

‘Short Works’, performed at Clayton Whites Hotel, the first of which was an

abbreviated production of Donizetti’s Don Pasquale staged by

Kathleen Stakenas with music director Daniela Pellegrino. If Il bravo had shown just what a complex brain-teaser an opera

libretto can be, then Stakenas and designer Angela Giulia Toso chose,

literally, to house the Don in a Rubik Cube - an apt metaphor for the

puzzles and problems posed for the aging Don by his duplicitous doctor,

Malatesta, his nephew Ernesto, and the latter’s amour, Norina. One column

of the Cube was withdrawn to reveal the Library where, after his ‘marriage’

to ‘Sofronia’, Pasquale would find his ‘wife’s’ pink pompons, pelicans and

ponies perching next to his decanters and leather-bound tomes, as she

squandered his fortune on fluffy frivolities. Pasquale never did manage to

twist the clues into the right place and solve the riddle, but Stakenas

told the tale clearly, though the necessary excisions weakened our

appreciation of the schemers’ motivations - though, in any case, I always

find their machinations rather too cruel given Pasquale’s ‘crimes’.

Simon Mechliński and Toni Nežić. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Simon Mechliński and Toni Nežić. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Toni Nežić’s Don Pasquale was morose and muddled, rather than pompous and

furious, and in his oversize suit and shirt looked a portrait of

misguidedness and misery. Although, despite a liberal sprinkling of

hair-whitener, Nežić didn’t look old enough to be Ernesto’s uncle, the

Croatian singer’s bass had a warm gravity and a persuasive maturity, and

his performance was consistent and engaging. As Norina, Barbara Cole Walton

displayed sheen and clarity at the top, and excellent intonation, but her

soprano was not equally weighted throughout her range, becoming a little

thin in the lower regions. She acted superbly though and, importantly, she

resisted over-acting as she commandeered the telephone, doubled the

butler’s salary, order to employ a hairdresser and jeweller to serve her

needs, and announced to the dismayed and deluded Pasquale that, as he

himself was too fat, old and decrepit, Ernesto would be her ‘cavalier’.

Antonio Mandrillo was a sweet-toned Ernesto, but his tenor lacks real heft

and he struggled a little with the dryness of the acoustic at Whites. Best

of the cast was Polish baritone Simon Mechliński: a wily and witty

Malatesta, he revealed a secure technique, a relaxed, agile baritone, and a

comfortable stage presence, manipulating his patient with glee and ease.

Nežić and Mechliński proved equally adept in their patter duet, while

Mandrillo and Cole Walton blended well during their nocturnal rendezvous in

the Don’s garden.

The following lunchtime, Bernstein à la carte proved less

satisfying. Director Roberto Recchia is a regular at Wexford and his Short

Work productions have offered much mirth and musical merit - including an

ingenious

L’elisir d’amore

in 2013,

La Cenerentola

the following year,

Donizetti's II Campanello

in 2016, and

Rigoletto

last year.

This celebration of Bernstein’s ‘100th birthday’ fell a little

flat though: not that the performances of the seven-strong ensemble were

less than spirited and technically assured, rather that the situation - a

party held for ‘Lenny’ in which each singer unwrapped their ‘present’, one

of Bernstein’s scores, thereby prompting an aria or ensemble from the said

work - felt somewhat contrived. Despite the complementary primary colours

of the chaps’ sassy suits and lasses’ satin frocks, the milieu - white

Ikea-cubes, champagne bottles and some bright balloons - was rather

charmless, and the opening number, a medley which overlaid West Side Story’s duet, ‘Tonight’, sung powerfully by Gemma

Summerfield and James Lui, and the Quintet and Chorus of the same name,

didn’t sit very comfortably. The proceedings took a little while to get

into their stride too, though Summerfield did sterling work establishing

the context and holding things together. A screen at the rear showed images

of Manhattan, film and score playbills, and helpfully provided a guide

through the works performed - useful given that the roster included both

the familiar and the rare.

Cast of Bernstein à la carte. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Cast of Bernstein à la carte. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

We were treated to numbers from Wonderful Town (including ‘What a

waste’ and ‘) and On the Town. ‘I can cook too’ from the latter

segued into La bonne cuisine, prompting a display of culinary

‘prowess’ from a team of chefs, who threw just about everything - including

a length of old rope, a rubber chicken and a decapitated fluffy bunny -

into the mix. Thankfully we were spared faux American accents, but some of

the numbers felt in need of a bit more schmaltz and jauntiness: ‘I am

easily assimilated’, from Candide would have been enhanced by a

dash more rhythmic hyperbole, though the cooks’ wooden spoons served as

admirable castanets; ‘Some other time’, from On the Town, felt a little underpowered.

Emma Nash gave a terrifically sparkling rendition of ‘Glitter and Be Gay’

though, and Summerfield’s ‘Somewhere’ was a highpoint - focused, poised and

beautifully phrased. Owain Browne, who acted suavely and confidently

throughout, turned On the Town’s ‘I Wish I Was Dead’ into a

brilliant drag act and strummed a guitar tunefully to accompany Ranald

McCusker’s reflective ‘It Must Be So’ (Candide). James Liu - cast

here, a little awkwardly, as the party stooge - was less successful in

‘Maria’ where, unfortunately, the opening gambit - the tenor struggled to

learn the song, freshly unwrapped from its box, to music director Tina

Chang’s annoyance and frustration - subsequently seemed all too close to

the bone as Liu’s improvisatory flights took him far from the home pitch.

But, ‘Lonely Town’ (On the Town) was more satisfying, in which Liu

was accompanied by the ensemble’s gentle humming.

Between the songs and ensembles we had readings from Bernstein’s letters,

though not all of the cast were equally adept at projecting their spoken

voices and I struggled to see the relevance of some of the readings to the

surrounding musical material.

Ranald McCusker and Emma Nash. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

Ranald McCusker and Emma Nash. Photo Credit: Paula Malone Carty.

As we neared the close, I Hate Music!: A Cycle of Five Kid Songs

offered some less frequently performed fare. After ‘The Wrong Note Rag’, in

which Summerfield and soprano Rosemary Clifford demonstrated crystal-clear

diction, we were, inevitably, urged to ‘Make Our Garden Grow’ ( Candide); the singing was impassioned and intense, though I wasn’t

convinced that the a cappella episode was harmonically accurate.

Sadly, this year’s performance schedule meant that I had to miss the third

of the Short Works, Puccini’s La fanciulla del West, but

I did enjoy an unexpected musical bonus when Sir Thomas Allen took the

opportunity to turn this year’s Dr Tom Walsh Lecture into a musical

retrospective of his career, sharing and illustrating anecdotes of his

early musical experiences: his father’s band playing; the encouragement of

the Physics teacher who was eager to share the treasures of his LP

collection with his young charge; the singer’s own early misconception that

German songs were known as ‘lides’.

“Life has been one long serenade,” said Sir Thomas, after dulcetly crooning

Don Giovanni’s ‘Deh vieni alla finestra’. One might say the same of

Wexford. For those not able to attend this year’s Festival, the live streaming of Il bravo

on Saturday 27th October at 8pm, offers an opportunity to share

in the Festival spirit.

Claire Seymour

Giordano:

Mala vita

Vito - Sergio Escobar, Annetiello - Leon Kim, Cristina - Francesca Tiburzi,

Amalia - Dorothea Spilger, Marco - Benjamin Cho, Nunzia - Anna Jeffers

Leoni:

L’oracolo

Uin-Scî - Leon Kim, Cim-Fen - Joo Won Kang, Hu-Tsin - Benjamin Cho, San-Lui

- Sergio Escobar, Ah-Joe - Elisabetta Farris, Hua-Quî - Louise Innes, Hu-Cî

- Cillian McCamley

Director - Rodula Gaitanou, Conductor - Francesco Cilluffo, Set and Costume

Designer - Cordelia Chisholm, Lighting Designer - Paul Hackenmueller,

Orchestra and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera

National Opera House, Wexford; Friday 19th October 2018.

Bolcom: Dinner at Eight

(European premiere)

Millicent Jordon - Mary Dunleavy, Oliver Jordon - Stephen Powell, Paula

Jordon - Gemma Summerfield, Carlotta Vance - Brenda Harris, Dan Packard -

Craig Irvin, Kitty Packard - Susannah Biller, Larry Renault - Richard Cox,

Lucy Talbot - Sharon Carty, Dr Joseph Talbot - Brett Polegato, Max Kane -

Ashley Mercer, Gustave - Sheldon Baxter, Miss Copeland - Maria Hughes, Tina

- Laura Margaret Smith, Miss Alden - Gabrielle Dundon, Eddie - Ranald

McCusker, Mr Hatfield - Henry Grant Kerswell, Zoltán - Feilimidh Nunan,

Supernumeraries - Alessandro Ambrosini, Elias Benito-Arranz, Chase Hopkins,

James Liu

Director - Tomer Zvulun, Conductor - David Agler, Set Designer - Alexander

Dodge, Costume Designer - Victoria Tzykun, Orchestra of Wexford Festival

Opera

National Opera House, Wexford; Saturday 20th October 2018.

Mercandante:

Il bravo

Il bravo - Rubens Pelizzari, Pisani - Alessandro Luciano, Foscari - Gustavo

Castillo, Luigi - Simon Mechliński, Teodora - Yasko Sato, Violetta -

Ekaterina Bakanova, Cappello -José de Eça, Marco - Toni Nežić, Un Messo -

Richard Shaffrey, Michelina - Ioana Constatin-Pipelea, Supernumeraries -

Susan Anderson, Sean Banfield, Martin Conway, Catherine Gaul, Colman

Hickey, Saran Moran, Sadhbh Murphy, Eoin O’Connor, Eoin Pinaqui, Alex

Saunders

Director - Renaud Doucet, Conductor - Jonathan Brandani, .Set & Costume

Designer - André Barbe, Lighting Designer - Paul Hackenmueller, Orchestra

and Chorus of Wexford Festival Opera

National Opera House, Wexford; Sunday 21st October 2018.

Donizetti:

Don Pasquale

Don Pasquale - Toni Nežić, Dr Malatesta - Simon Mechliński, Ernesto -

Antonio Mandrillo, Norina - Barbara Cole Watson, Carlino - Henry Grant

Kerswell

Music Director - Daniela Pellegrino, Stage Director - Kathleen Stakenas,

Stage & Costume Designer - Angela Giulia Toso, Lighting Designer -

Johann Fitzpatrick

Whites Clayton Hotel; Saturday 20th October 2018.

Bernstein à la carte

Gemma Summerfield (soprano), Emma Nash (soprano), Rosemary Clifford

(mezzo-soprano), James Liu (tenor), Ranald McCusker (tenor), Jevan Mcauly

(bass), Owain Browne (bass)

Music Director - Tina Chang, Stage Director - Roberto Recchia, Stage &

Costume Designer - Angela Giulia Toso, Lighting Designer - Johann

Fitzpatrick

Whites Clayton Hotel; Sunday 21st October 2018.