The only thing I minded were some inconsistencies of tuning in the opening

two minutes and at the very end. The detailed sonics lack some of the

mystery that Stéphane Denève brings out so well at various points in the

studio recording of the work,

reviewed here. But the clarity of detail also

brings ample compensation. The music is conducted with keen stylistic

awareness by Mikko Franck, music director of the French radio orchestra

that is heard here (and former music director of the Finnish National

Opera).

There will probably never be an absolute “best” recording of this

remarkable work. It has twenty singing roles divided among eight or so

singers, all in a work that lasts some 43 minutes. Characters rarely sing

at the same time, and some passages are choral or orchestral. Thus, as

simple arithmetic tells us, each role contains only a few minutes of

singing!

The singers on this recording characterize their various roles vividly and,

in a few cases (Grandfather Clock, Fire), are more precise with the pitches and articulation than are the

singers in the Denève recording. I was surprised that the two singers who

participate in both the Denève recording and this one (Pasturaud and

Piolino) seem even more in command in this concert recording than they

already were when they had the advantage of studio conditions and the

possibility of multiple retakes. Perhaps the presence of an audience that

could understand, without supertitles, the nuances of the text that was

being sung, made a difference.

The discovery for me is Sabine Devieilhe, as Fire,

Princess, and Nightingale. Her coloratura singing is as close to perfection

as humanly possible. Her lyrical singing is no less wondrous. I hope to

hear her in much other repertoire soon. (I have read praise of her three

recital discs for the French firm Erato.) I must also praise three of the

other singers who, like Devieilhe, were not on the Denève recording. The

renowned Nathalie Stutzmann brings enormous warmth and seeming

spontaneity to her three roles.

Jean-François Lapointe takes care to sing, not talk-sing, Grandfather

Clock. And, as the Child,

Chloé Briot reveals her impressively diverse vocal abilities

ever more as the opera unfolds. (Briot has a touch of wobble on sustained

notes, but is otherwise perhaps the best Child on any recording.) The four

“animals” who speak, near the end of the opera, are members of the French

Radio Chorus, and the booklet nicely names them.

They do their lines superbly.

The libretto is given complete, including the extensive stage directions,

all in the superb old Felix Aprahamian translation. But the latter could

use a bit of updating or clarification by now. For example, the character

known as La Bergère is translated as The Sofa, which seems to imply a

largish object. But the stage directions make clear that this piece of

upholstered furniture is smaller than the big armchair (Le Fauteuil, sung

by a bass), which of course is why Ravel assigns the role to a higher voice

(mezzo-soprano). Perhaps we might call it (or her) a “Small Upholstered

Seat.”

In addition to famous older recordings (see the previous review), I should

add that there are two different Glyndebourne DVD versions of this opera.

Both pair the work with Ravel’s first opera, L’heure espagnole,

and both are apparently wonderful in different ways.

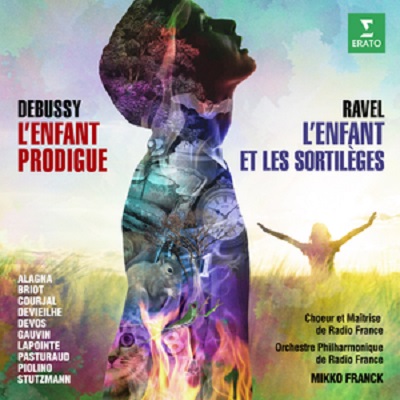

The opera comes as part of a 2-CD set, with two works by Debussy. One is

another “child” work: Debussy’s The Prodigal Son (1884). Of

course, this child is fully grown, for the story is the one in Luke 18

about a son who has left his father and brother and wasted his inheritance,

then returns and is forgiven. The other work is a little-known early

symphonic movement.

There is much less recorded competition for the Debussy cantata (or, in its

alternate title, “operatic scene”) than for Ravel’s opera. And for good

reason: it’s an early work, composed to please the professors at the

Conservatoire and help win Debussy the Prix de Rome. (It succeeded!)

Debussy was pleased enough with it to allow it to be published twenty-four

years later. Still, whole chunks of it sound highly conventional. My

favorite passage is the opening prelude, which is clearly meant to sound

exotic—in the manner of Rimsky-Korsakov, Borodin, and Balakirev—so as to

place the listener in the ancient Middle East.

Whatever the mixed merits of the piece itself, the singing here is

magnificent, as one might expect from a project that includes the renowned

Roberto Alagna (as the Son).

The soprano, Karina Gauvin, sings the role of the mother to perfection.

I had heard of Gauvin and will now look for other recordings by her. Lia’s

aria, the first vocal number in the work, has been often recorded

separately, but surely never better. The famous

“Cortège et air de danse,”

a self-enclosed orchestral piece likewise sometimes performed apart from

the cantata, beautifully conveys the graciousness of family and community

life from which the wastrel Azaël has chosen to absent himself.

The vivid sonics capture every detail of this concert performance of L’enfant prodigue. The booklet gives an antiquated singing

translation that takes some effort to decode.

There have been at least three previous recordings, including a monophonic

one featuring an exemplary French tenor, Henri Legay, and a much more

recent one that is part of a 2-CD set of Debussy’s various Prix de Rome

compositions, conducted by Hervé Niquet. (The latter set, which comes with

a small book, is sponsored by the enterprising Center for French Romantic

Music, located at the Palazzetto Bru Zane in Venice.) The best known

recording is a 1982 release conducted by Gary Bertini and featuring Jessye

Norman, José Carreras, and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, all in splendid voice.

But I am nearly always happier hearing Francophones singing French, as in

the new recording.

The early Debussy symphonic movement in B minor survives only as a piece

for piano four-hands and has been recorded several times in that guise.

There is no evidence that Debussy ever got around to orchestrating it.

The style is remarkably varied: its opening is surprisingly Brahmsian. (For further description, see the chapter that I wrote on French

symphonies in the book

The Nineteenth-Century Symphony, ed. D. Kern Holoman.) Here the movement is heard in a somewhat dense but workable

orchestration by Colin Matthews, conducted rather straightforwardly by

Franck. (Naxos has released a recording that uses an orchestration, by

American composer-arranger Tony Finno, that feels more playful and

exploratory than the Matthews. Finno’s version is made particularly

attractive by conductor Jun Märkl’s frequent and apt-feeling changes of

tempo.)

The Erato 2-CD set is available at the price of a single CD. It thus

represents a remarkable bargain, and nobody will regret snapping it up. If

you have never encountered Ravel’s L’enfant et les sortilèges, I suggest that you treat yourself to this recording, or to any of the

aforementioned ones (including, by all means, the atmospheric Denève). But

make sure you read the delightful libretto and detailed stage

directions--either beforehand or while listening.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here by kind permission.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book.