11 Jan 2019

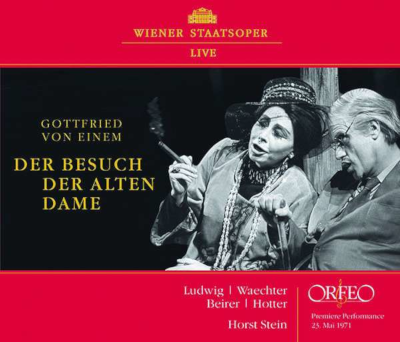

Gottfried von Einem’s The Visit of the Old Lady Now on CD

Gottfried von Einem was one of the most prominent Austrian composers in the 1950s–70s, actively producing operas, ballets, orchestral, chamber, choral works, and song cycles.

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

The voices of six women composers are celebrated by baritone Jeremy Huw Williams and soprano Yunah Lee on this characteristically ambitious and valuable release by Lontano Records Ltd (Lorelt).

As Paul Spicer, conductor of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire Chamber Choir, observes, the worship of the Blessed Virgin Mary is as ‘old as Christianity itself’, and programmes devoted to settings of texts which venerate the Virgin Mary are commonplace.

Ethel Smyth’s last large-scale work, written in 1930 by the then 72-year-old composer who was increasingly afflicted and depressed by her worsening deafness, was The Prison – a ‘symphony’ for soprano and bass-baritone soloists, chorus and orchestra.

‘Hamilton Harty is Irish to the core, but he is not a musical nationalist.’

‘After silence, that which comes closest to expressing the inexpressible is music.’ Aldous Huxley’s words have inspired VOCES8’s new disc, After Silence, a ‘double album in four chapters’ which marks the ensemble’s 15th anniversary.

A song-cycle is a narrative, a journey, not necessarily literal or linear, but one which carries performer and listener through time and across an emotional terrain. Through complement and contrast, poetry and music crystallise diverse sentiments and somehow cohere variability into an aesthetic unity.

One of the nicest things about being lucky enough to enjoy opera, music and theatre, week in week out, in London’s fringe theatres, music conservatoires, and international concert halls and opera houses, is the opportunity to encounter striking performances by young talented musicians and then watch with pleasure as they fulfil those sparks of promise.

“It’s forbidden, and where’s the art in that?”

Dublin-born John F. Larchet (1884-1967) might well be described as the father of post-Independence Irish music, given the immense influenced that he had upon Irish musical life during the first half of the 20th century - as a composer, musician, administrator and teacher.

The English Civil War is raging. The daughter of a Puritan aristocrat has fallen in love with the son of a Royalist supporter of the House of Stuart. Will love triumph over political expediency and religious dogma?

Beethoven Symphony no 9 (the Choral Symphony) in D minor, Op. 125, and the Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. 80 with soloist Kristian Bezuidenhout, Pablo Heras-Casado conducting the Freiburger Barockorchester, new from Harmonia Mundi.

A Louise Brooks look-a-like, in bobbed black wig and floor-sweeping leather trench-coat, cheeks purple-rouged and eyes shadowed in black, Barbara Hannigan issues taut gestures which elicit fire-cracker punch from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

‘Signor Piatti in a fantasia on themes from Beatrice di Tenda had also his triumph. Difficulties, declared to be insuperable, were vanquished by him with consummate skill and precision. He certainly is amazing, his tone magnificent, and his style excellent. His resources appear to be inexhaustible; and altogether for variety, it is the greatest specimen of violoncello playing that has been heard in this country.’

Baritone Roderick Williams seems to have been a pretty constant ‘companion’, on my laptop screen and through my stereo speakers, during the past few ‘lock-down’ months.

Melodramas can be a difficult genre for composers. Before Richard Strauss’s Enoch Arden the concept of the melodrama was its compact size – Weber’s Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz, Georg Benda’s Ariadne auf Naxos and Medea or even Leonore’s grave scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio.

Gottfried von Einem was one of the most prominent Austrian composers in the 1950s–70s, actively producing operas, ballets, orchestral, chamber, choral works, and song cycles.

Of his nine operas, three became relatively well known, including Dantons Tod (Danton’s Death, 1947, after Georg Büchner) and Der Prozess (The Trial, 1953, after Franz Kafka). Critics hailed both for their dramatic effectiveness and, not least, for the way von Einem’s music lets the vocal lines come through clearly.

Now we get a CD re-release of the third and last of von Einem’s best-known operas: Der Besuch der alten Dame (The Visit of the Old Lady, 1971). This one is in three tight acts and is based on a world-famous play with the same title by Swiss playwright Friedrich Dürrenmatt. The play (first seen in 1956) has been adapted numerous times, with its title usually shortened in English to The Visit. Notable versions include a film with Ingrid Bergman and, more recently, a musical with Chita Rivera.

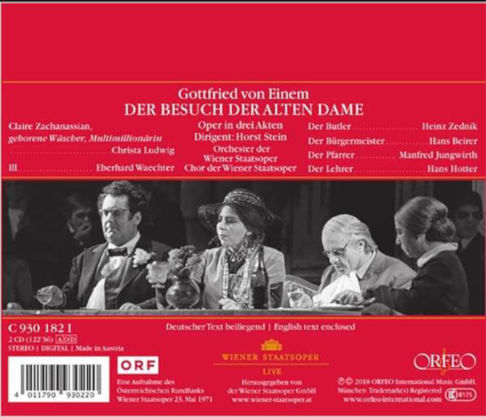

Von Einem’s opera, using a libretto adapted jointly by the composer and the playwright, is a powerful statement, thanks in large part to the vivid reading of the title role given in this recording of the premiere performance (May 23, 1971) by one of the greatest singers and operatic performers of the second half of the twentieth century: mezzo-soprano Christa Ludwig.

The plot is simple and ingenious. A poor woman, Klara, leaves her hometown, pregnant and in near-despair. The child dies, and Klara marries a series of nine husbands, becoming in the process a multi-millionaire and changing her first name to Claire. She returns to the town with several of those husbands in tow, some servants whom she has blinded or castrated (several very large servants carry her around on a litter), and an empty coffin (waiting to be filled—with whose body?). The town has become impoverished through Claire’s clandestine, vengeful business dealings. Claire offers the townspeople a vast sum of money if they will put to death Alfred Ill, the man who got her pregnant.

Much of the play involves the gradual revelation (to the townspeople and its leaders—the latter are all male of course, like Claire’s large retinue) of the events and intentions that I just mentioned. The ending of the play and opera—though apparently not of the film—is straightforward: Alfred Ill is put to death. Claire and her small army of males leave with the coffin (now presumably filled), and the opera ends with a jubilant chorus. Play and opera drip with irony and social criticism, like much Brecht; they are also often uncomfortably comical, again like Brecht. I couldn’t help but think, as I listened, how relevant the opera’s messages remain: about power and greed, individual cruelty and cowardly group-think.

Von Einem’s music here is immensely varied, reminding me at times of Mahler, Stravinsky, Prokofiev, or Orff. The vocal lines vary between angular and declamatory, rarely becoming as lyrical as in, say, Britten. The orchestra is deployed cagily, allowing us to hear the sung lines clearly. (Some present-day opera composers could learn a lesson or two here.) In compensation, the orchestra is given a prelude to each of the three acts, plus seven interludes between scenes. These orchestral passages are mainly dominated by percussion, with much darkly mysterious (primitivistic?) pounding. The result is a disturbing series of reminders of the grimness, vindictiveness, and violence that—as portrayed by the dramatist and composer—underlie so many human interactions. The preludes and interludes could possibly make an interesting concert work in themselves.

In 1971, Christa Ludwig was at her peak effectiveness, the voice covering a wide range with total solidity and turning on a dime from silky to snarly. We hear the same astounding singer who, in the years around that time, made classic recordings of such roles as Dalila, Waltraute, and (in German—and I strongly recommend that you seek the recording out!) Carmen. With her then-husband Walter Berry she made marvelous recordings of Mahler’s Wunderhorn songs, marvelously conducted by Leonard Bernstein, and of excerpts from Richard Strauss’s Die Frau ohne Schatten. I will never forget hearing Ludwig in the summer of 1971 at Tanglewood (a few months after the von Einem premiere), singing the fourth movement, “Urlicht,” mesmerizingly, in the Mahler Second under (again) an inspired Bernstein. (I was singing in the Tanglewood Festival Chorus and thus seated far behind Ludwig, but that luminous voice poured out: forward, backward, and to all sides, conveying the sentiment of the words without ever breaking the musical line.)

Ludwig’s gorgeous, articulate monster is joined (and castigated, etc.) by singers of similar renown: Eberhard Wächter (who was the title character in Giulini’s acclaimed Don Giovanni recording and John the Baptist in Solti’s equally potent Salome), Hans Hotter (Wotan in the legendary Solti Ring), Heinz Zednik (whose Mime was one of the many gems of the Met’s late-1980s Ring CDs and video), and Manfred Jungwirth (Ochs in the Carlos Kleiber Rosenkavalier). Hotter and Jungwirth are sometimes wobbly, as is Hans Beirer in the role of the town’s mayor. But all three certainly put their roles across. Wächter is steady and clear, conveying through understatement the bafflement and agony of Claire’s chosen victim. Zednik is perfect as Claire’s officious Butler. The many smaller roles are performed with great panache by artists from the roster of the Vienna State Opera (e.g., the much-recorded light soprano Emmy Loose). The orchestra plays with vigor or delicacy, as required, and conductor Horst Stein cuts short the grateful applause after each scene in order to get the music and drama going again.

The recording conveys all the thrust and sardonic glint of a live performance. I hope it will spur opera companies to mount this amazing, insightful work. In the work’s early years there were a few stagings in such places as Berlin, London, and San Francisco, the latter directed by the filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola. Maybe another such wave of productions is starting: the opera was performed in Vienna during the 2017-18 season, at the Theater an der Wien. The marvelous singers Katarina Karnéus and Russell Braun portrayed the multimillionaire and her former lover.

Despite the wonders on display in the opening-night performance captured on these two CDs, we could also use a state-of-the-art studio recording, in which purely musical and vocal values were emphasized more in certain roles and in which artful microphone placement would catch various subtleties and nuances from the orchestra. That (hypothetical) new recording should include a libretto. Here we get only an essay, some insightful reminiscences from Christa Ludwig, and a detailed synopsis. All of this is translated and copyedited a bit roughly, e.g., “improve” instead of “improvise.” I was particularly grateful for the synopsis, but got a more precise sense once I located a copy of the published score, which contains numerous helpful and even revelatory stage directions and other performance indications.

Dare one hope that the 1972 Coppola staging was videotaped? Interestingly, 1972 was the same year that Coppola’s film The Godfather —another ugly story of power—was released. Der Besuch is an opera made to be seen as well as heard.

Even without visuals, though, this recording of a little-known but major work is something to treasure. More generally, it reminds us that the musical world would do well to remember and revive the many marvelous twentieth-century works that were at least partly rooted in triadic tonality and that won, at the time, the loyalty and affection of performers and audiences alike. For two other largely forgotten works of that sort, both of them fairy-tale-like in nature, see my reviews here of Laci Boldemann’s Black Is White, Says the Emperor (1965) and Otakar Ostrčil’s Jack’s Kingdom (1934). The former is in Swedish, the latter in Czech, but good singing translations would make them work wonderfully in the English-speaking world as well.

Ralph P. Locke

The above review is a lightly revised version of one that first appeared in American Record Guide. It appears here by kind permission of ARG.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback, and the second is also available as an e-book. His reviews appear in various online magazines, including The Arts Fuse, NewYorkArts, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer.