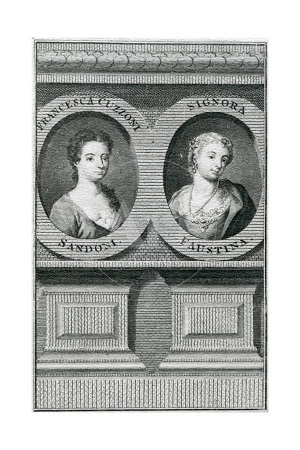

In 1720s London, the ‘nightingales’ at war were Italian prima donnas

Francesca Cuzzoni and Faustina Bordoni, represented at this London Handel

Festival concert by Mary Bevan and Mhairi Lawson respectively, and

supported by Christian Curnyn’s Early Opera Company. The performances of

these eighteenth-century queens of the opera stage, at the Royal Academy of

Music, led to mutual international renown. And, it was the story of their

repute and rivalry which actress Lindsay Duncan recounted with telling dry

wit at St John’s Smith Square, through excerpts from letters, diaries and

newspaper reports interweaved between the arias which made the singers’

names in London and abroad.

To summarise the tale, Cuzzoni made her London debut in 1723, as Teofane in

Handel’s Ottone at the King’s Theatre, Haymarket, a performance

which caused a sensation. Many attested to her skill. German

flautist-composer Johann Joachim Quantz appreciated her ‘tender and

touching’ expression and the grace with which she embellished melodies.

Charles Burney recorded that she ‘rendered pathetic whatever she sung’ and

that her ability to control and adjust musical phrases with rubato made her

a ‘complete mistress of her art.’ The Italian castrato Giovanni Mancini

eulogised: ‘This woman possessed all the necessary requisites to be truly

great. ... Her high tones were unequalled and perfect; intonation was born

in her. She had an original and inventive mind ... and her choice of

embellishments was something new. She left aside the usual and common and

made her singing rare and wonderful.’

After Margherita Durastanti’s retirement, for two years Cuzzoni shared the

London stage with the mezzosoprano castrato Senesino, an unchallenged prima

donna. And, when Faustina Bordoni joined the Royal Academy in

1725, the management must have been delighted that her skills and qualities

would complement those of Cuzzoni. A mezzo-soprano who excelled in rapid

passagework, she was also a fine actress. The feisty roles which Handel

would compose for Faustina were characterised by defiance, even aggression.

One scholar has described the different attributes of the two singers thus:

‘Cuzzoni’s arias were often the pathetic sicilianos that showcased her

expressive, cantabile singing. When in disguise, her characters masqueraded

as shepherdesses, whereas Faustina’s characters disguised themselves only

as men and warriors. The shepherdess had idyllic girlish qualities: she was

innocent, pure, delicate, and coy. She inhabited the pastoral world.

Faustina’s characters might angrily chastise male betrayers, but Cuzzoni’s

only despaired and mourned in response to betrayal’.

[1]

Faustina’s reputation preceded her to the English capital. As early as 30 th March 1723, the London Journal reported that ‘as soon as

Cuzzoni’s time is out we are to have another over; for we are assured

Faustina, the finest songstress at Venice, is invited, whose voice, they

say, exceeds what we have already here.’

Quantz gave Burney an account of Faustina’s singing: ‘Faustina had a

mezzo-soprano voice that was less dear than penetrating. […] Her execution

was articulate and brilliant. She had a fluent tongue for pronouncing words

rapidly and distinctly, and a flexible throat for divisions, with so

beautiful a trill that she could put it in motion upon short notice just

when she would. […] She sang adagios with great passion and expression, but

was not equally successful if such deep sorrow were to be impressed on the

hearer as might require dragging, sliding, or notes of syncopation and

tempo rubato.’ Burney himself added that Faustina ‘invented a new kind of

singing by running divisions with a neatness and velocity which astounded

all who heard her. She had the art of sustaining a note longer, in the

opinion of the public, than any other singer, by taking her breath

imperceptibly. Her beats and trills were strong and rapid; her intonation

perfect; and her professional perfections were enhanced by a beautiful

face, a symmetric figure, though of small stature, and a countenance and

gesture on the stage which indicated an entire intelligence of her part.’

The personal rivalry between the singers, stoked by their partisan

supporters, was surely not what the Academy intended or desired, as this

observation by Pier Francesco Tosi, an Italian castrato who taught in

London in the late 1720s, suggests: ‘Their merit is superior to all praise;

for with equal strength, though in different styles, they help to keep up

the tottering profession from immediately falling into ruin. The one is

inimitable for a privileged gift of singing, and enchanting the world with

an astonishing felicity in executing difficulties with a brilliancy, I know

not whether derived from nature or art, which pleases to excess. The

delightful, soothing, cantabile of the other, joined to the sweetness of a

fine voice, a perfect intonation, a strictness of time, and the rarest

productions of genius in her embellishment, are qualifications as peculiar

and uncommon as they are difficult to be imitated. The pathos of the one

and the rapidity of the other are distinctly characteristic. What a

beautiful mixture it would be, if the excellencies of these two angelic

beings could be united in a single individual.’

Mary Bevan. Photo credit: Victoria Cadisch.

Mary Bevan. Photo credit: Victoria Cadisch.

The behaviour of the two operatic queens was far from ‘angelic’, however.

It’s reported that at Cuzzoni’s first rehearsal with Handel she refused to

sing ‘Falsa imagine’ from Ottone, as it had been written

for Durastini; whereupon Handel called her a “veritable devil”, picked her

up and threatened to throw her out of the window. Opposing camps of

influential supporters quickly formed vociferous ranks: on Cuzzoni’s side

were Lady Pembroke and Lady Walpole; leading the Faustina camp were Sir

Robert Walpole, Lady Cowper, Lady Delaware and the Countess of Burlington.

Race-horses were named after them; ‘Cuzzoni’ and ‘Faustina’ ran against

each other at Newmarket. Lord John Hervey wrote: ‘In short, the whole world

is gone mad upon this dispute. No Cuzzonist will go to a tavern with a

Faustinian. And the ladies of one party have scratched those of the other

out of their lists of visits.’

The incident most often cited as evidence of the divas’ cattiness is a

scandalous hair-pulling fist-fight that erupted during a performance of

Bonocini’s Astianatte in 1727. The London Journal

reported restrainedly, on 10 June, that ‘A great disturbance happened at

the opera, occasioned by the partisans of the two celebrated rival ladies,

Cuzzoni and Faustina. The contention at first was only carried on by

hissing on one side and clapping on the other, but proceeded at length to

the melodious use of cat-calls and other accompaniments, which manifested

the zeal and politeness of that illustrious assembly’. Dr John Arbuthnot

was more graphic in his account, The devil to pay at St. James’s:

‘But who would have thought the Infection should reach the Hay-Market, and

inspire two Singing Ladies to pull each other’s coiffs? ... It is certainly

an apparent Shame that two such well bred Ladies should call Bitch and

Whore, should scold and fight like any Billingsgate.’

[2]

Duncan told an entertaining tale - and I hope that Opera Today

readers will indulge my rather lengthy summary - but the musical

illustration of this historical vocal posing and posturing was less

engaging. This was in no way a reflection on the undoubted talents and

flair of Bevan and Lawson; nor the lively buoyancy of the EOC’s

accompaniment and their spirited rendition of overtures from Handel’sOttone, Alessandro and Admeto, and Porpora’s Polifemo. But, the sequence of arias represented the dying days of

the Academy, and simply did not offer sufficient contrast, character and

inspired creativity to sustain the narrative, no matter how precipitously

Curnyn commenced the musical numbers, sometimes almost interrupting

Duncan’s spoken text.

Bevan and Lawson had the challenge of summoning characters with immediacy

and removed from the dramatic context. When Handel’s music works its magic,

as in ‘Che sento? Se pietà’ from Giulio Cesare the drama flowed;

here, Bevan’s pianissimo decorative ascents in the da capo were brilliantly

executed, and lyricism and theatre were nicely balanced. The first half of

the programme focused on Alessandro and the eponymous

protagonist’s marital woes, as two wives fought for his love. Lawson’s

account of Rossane’s ‘Lusinghe più care’ was countered by Bevan’s lilting

rendition of Lisaura’s ‘Che tirannia d’Amor!’, which exploited Cuzzoni’s

trademark siciliana silkiness, and showcased Bevan’s range and poise.

‘Brilla nell’alma’ from the same opera was designed to show off Faustina’s

coloratura pyrotechnics but while Lawson was light, agile and precise,

there was almost too much gracefulness - sparkle but not true fieriness.

Mhairi Lawson. Photo credit: Lloyd Smith Photography.

Mhairi Lawson. Photo credit: Lloyd Smith Photography.

There were other operatic dramas that might have been more vigorously and

viscerally brought to life. In Admeto, the wife and former lover -

Alceste (Faustina) and Antigona (Cuzzoni) respectively - fight over the

dying King Admetus of Thessaly, but here we had only the overture. In Siroe, re di Persia Handel pitted Emira - the daughter of Asbite,

King of Cambaya, and Siroe’s lover (Bordoni) - against Laodice, Cosroe’s

mistress and Arasse’s sister (Cuzzoni) (the plot’s the usual seria

cat’s- cradle), but here we had only one aria, ‘Torrente cresciuto’ in

which Bevan deployed her glossy soprano to full effect and essayed some

coloratura panache in the da capo.

We also had arias from Porpora’s Arianna in Nasso (‘Miseri

sventurati, poveri affetti miei’/Cuzzoni) and Hasse’s Cleofide

(‘Qual tempesta d’affetti … Son qual misera colomba’/Faustina); in the

former Bevan’s intonation and security were impressive as the vocal line

leapt impetuously; in the latter, the EOC Orchestra supplied welcome

dynamism, while Lawson waltzed through the voice-twisters with ease. But,

if we haven’t heard such operas often in the past two three hundred years,

there’s probably good reason. That said, there were plentiful musical

treats, such as the lovely oboe obbligato in Faustina’s ‘Quell’innocente,

afflitto core’ from Riccardo Primo, Rè D’Inghilterra.

One couldn’t fault the musicianship and the SJSS audience seemed delighted

to have been beguilingly entertained and educated. But, there was a

distinct lack of diversity and drama, given the theatrical exuberance of

the feted queens whose exploits on and off the stage were here celebrated.

Claire Seymour

Handel and the Rival Queens

: Early Opera Company

Mhairi Lawson (Faustina Bordoni), Mary Bevan (Francesca Cuzzoni), Lindsay

Duncan (Narrator), Christian Curnyn (Director)

Handel - Overture to Ottone HWV15, ‘Spietati, io vi giurai ( Rodelinda HWV19), ‘Che sento? … Se pietà’ (Giulio Cesare

HWV17), Overture to Alessandro HWV21, ‘Lusinghe più care … Che

tirannia d’Amor!’ (Alessandro), ‘Brilla nell’alma ( Alessandro), Overture to Admeto HWV22, ‘Torrente

cresciuto (Siroe, re di Persia HWV24), ‘Quell’innocente, afflitto

core (Riccardo primo, re d’Inghilterra HWV23); Porpora - Overture

to Polifemo, ‘Miseri sventurati, poveri affetti miei ( Arianna in Nasso); Hasse - ‘Qual tempest d’affetti … Son qual

misera colomba’ (Cleofide)’; Handel - ‘Placa l’alma, quieta il

petto!’ (Alessandro).

St John’s Smith Square, London; 24th April 2019.

[1]

Wier, C.R. (2010) ‘A nest of nightingales: Cuzzoni and Senesino at

Handel’s Royal Academy of Music’, Theatre Survey 51(2):

247-73.

[2]

See Wierzbicki, J. (2001). ‘Dethroning the Divas: Satire Directed

at Cuzzoni and Faustina’. The Opera Quarterly, 17(2),

175-96.