The pure and noble Rhine-gold Alberich seized, divorced it from the waters' depth, and wrought there from with cunning art a ring that lent him rulership of all his race, the Nibelungen: so he became their master, forced them to work for him alone, and amassed the priceless Nibelungen-Hoard, whose greatest treasure is the Tarnhelm, conferring power to take on any shape at will, a work that Alberich compelled his own brother Reigin (Mime = Eugel) to weld for him. Thus armoured, Alberich made for mastery of the world and all that it contains.

The race of Giants, boastful, violent, ur-begotten, is troubled in its savage ease: their monstrous strength, their simple mother-wit, no longer are a match for Alberich's crafty plans of conquest: alarmed they see the Nibelungen forging wondrous weapons, that one day in the hands of human heroes shall cause the Giants' downfall.—This strife is taken advantage of by the race of Gods, now waxing to supremacy. Wotan bargains with the Giants to build the Gods a Burg from whence to rule the world in peace and order; their building finished, the Giants ask the Nibelungen-Hoard in payment. The utmost cunning of the Gods succeeds in trapping Alberich; he must ransom his life with the Hoard; the Ring alone he strives to keep:—the Gods, well knowing that in it resides the secret of all Alberich's power, extort from him the Ring as well: then he curses it; it shall be the ruin of all who possess it. Wotan delivers the Hoard to the Giants, but means to keep the Ring as warrant of his sovereignty: the Giants [302] defy him, and Wotan yields to the counsel of the three Fates (Norns), who warn him of the downfall of the Gods themselves.

Now the Giants have the Hoard and Ring safe-kept by a monstrous Worm in the Gnita- (Neid-) Haide [the Grove of Grudge]. Through the Ring the Nibelungs remain in thraldom, Alberich and all. But the Giants do not understand to use their might; their dullard minds are satisfied with having bound the Nibelungen. So the Worm lies on the Hoard since untold ages, in inert dreadfulness: before the lustre of the new race of Gods the Giants' race fades down and stiffens into impotence; wretched and tricksy, the Nibelungen go their way of fruitless labour. Alberich broods without cease on the means of gaining back the Ring.

In high emprise the Gods have planned the world, bound down the elements by prudent laws, and devoted themselves to most careful nurture of the Human race. Their strength stands over all. Yet the peace by which they have arrived at mastery does not repose on reconcilement: by violence and cunning was it wrought. The object of their higher ordering of the world is moral consciousness: but the wrong they fight attaches to themselves. From the depths of Nibelheim the conscience of their guilt cries up to them: for the bondage of the Nibelungen is not broken; merely the lordship has been reft from Alberich, and not for any higher end, but the soul, the freedom of the Nibelungen lies buried uselessly beneath the belly of an idle Worm: Alberich thus has justice in his plaints against the Gods. Wotan himself, however, cannot undo the wrong without committing yet another: only a free Will, independent of the Gods themselves, and able to assume and expiate itself the burden of all guilt, can loose the spell; and in Man the Gods perceive the faculty of such free-will. In Man they therefore seek to plant their own divinity, to raise his strength so high that, in full knowledge of that strength, he may rid him of the Gods' protection, to do of his free will what his own mind inspires. [303] So the Gods bring up Man for this high destiny, to be the canceller of their own guilt; and their aim would be attained even if in this human creation they should perforce annul themselves, that is, must part with their immediate influence through freedom of man's conscience. Stout human races, fruited by the seed divine, already flourish: in strife and fight they steel their strength; Wotan's Wish-maids shelter them as Shield-maids, as Walküren lead the slain-in-fight to Walhall, where the heroes live again a glorious life of jousts in Wotan's company. But not yet is the rightful hero born, in whom his self-reliant strength shall reach full consciousness, enabling him with the free-willed penalty of death before his eyes to call his boldest deed his own. In the race of the Wälsungen this hero at last shall come to birth: a barren union is fertilised by Wotan through one of Holda's apples, which he gives the wedded pair to eat: twins, Siegmund and Sieglinde (brother and sister), spring from the marriage. Siegmund takes a wife, Sieglinde weds a man (Hunding); but both their marriages prove sterile: to beget a genuine Wälsung, brother and sister wed each other. Hunding, Sieglinde's husband, learns of the crime, casts off his wife, and goes out to fight with Siegmund. Brünnhild, the Walküre, shields Siegmund counter to Wotan's commands, who had doomed him to fall in expiation of the crime; already Siegmund, under Brünnhild's shield, is drawing sword for the death-blow at Hunding—the sword that Wotan himself once had given him—when the god receives the blow upon his spear, which breaks the weapon in two pieces. Siegmund falls. Brünnhild is punished by Wotan for her disobedience: he strikes her from the roll of the Walküren, and banishes her to a rock, where the divine virgin is to wed the man who finds and wakes her from the sleep in which Wotan plunges her; she pleads for mercy, that Wotan will ring the rock with terrors of fire, and so ensure that none save the bravest of heroes may win her.—After long gestation the outcast Sieglinde gives birth in the forest to [304] Siegfried (he who brings Peace through Victory): Reigin (Mime), Alberich's brother, upon hearing her cries, has issued from a cleft and aided her: after the travail Sieglinde dies, first telling Reigin of her fate and committing the babe to his care. Reigin brings up Siegfried, teaches him smithery, and brings him the two pieces of the broken sword, from which, under Mime's directions, Siegfried forges the sword Balmung. Then Mime prompts the lad to slay the Worm, in proof of his gratitude. Siegfried first wishes to avenge his father's murder: he fares out, falls upon Hunding, and kills him: only thereafter does he execute the wish of Mime, attacks and slays the Giant-worm. His fingers burning from the Worm's hot blood, he puts them to his mouth to cool them; involuntarily he tastes the blood, and understands at once the language of the woodbirds singing round him. They praise Siegfried for his glorious deed, direct him to the Nibelungenhoard in the cave of the Worm, and warn him against Mime, who has merely used him as an instrument to gain the Hoard, and therefore seeks his life. Siegfried thereon slays Mime, and takes the Ring and Tarnhelm from the Hoard: he hears the birds again, who counsel him to win the crown of women, Brünnhild. So Siegfried sets forth, reaches Brünnhild's mountain, pierces the billowing flames, and wakes her; in Siegfried she joyfully acclaims the highest hero of the Wälsung-stem, and gives herself to him: he marries her with Alberich's ring, which he places on her finger. When the longing spurs him to new deeds, she gives him lessons in her secret lore, warns him of the dangers of deceit and treachery: they swear each other vows, and Siegfried speeds forth.

A second hero-stem, sprung likewise from the Gods, is that of the Gibichungen on the Rhine: there now bloom Gunther and Gudrun, his sister. Their mother, Grimhild, was once overpowered by Alberich, and bore him an unlawful son, Hagen. As the hopes and wishes of the Gods repose on Siegfried, so Alberich sets his hope of gaining back the Ring on his hero-offspring Hagen. Hagen is [305] sallow, glum and serious; his features are prematurely hardened; he looks older than he is. Already in his childhood Alberich had taught him mystic lore and knowledge of his father's fate, inciting him to struggle for the Ring: he is strong and masterful; yet to Alberich he seems not strong enough to slay the Giant-worm. Since Alberich has lost his power, he could not stop his brother Mime when the latter sought to gain the Hoard through Siegfried: but Hagen shall compass Siegfried's ruin, and win the Ring from his dead body. Toward Gunther and Gudrun Hagen is reticent,—they fear him, but prize his foresight and experience: the secret of some marvellous descent of Hagen's, and that he is not his lawful brother, is known to Gunther: he calls him once an Elf-son.

Gunther is being apprised by Hagen that Brünnhild is the woman most worth desire, and excited to long for her possession, when Siegfried speeds along the Rhine to the seat of the Gibichungs. Gudrun, inflamed to love by the praises he has showered on Siegfried, at Hagen's bidding welcomes Siegfried with a drink prepared by Hagen's art, of such potence that it makes Siegfried forget his adventure with Brünnhild and marriage to her. Siegfried desires Gudrun for wife: Gunther consents, on condition that he helps him win Brünnhild. Siegfried agrees: they strike blood-brothership and swear each other oaths, from which Hagen holds aloof.—Siegfried and Gunther set out, and arrive at Brünnhild's rocky fastness: Gunther remains behind in the boat; Siegfried for the first and only time exerts his power as Ruler of the Nibelungen, by putting on the Tarnhelm and thereby taking Gunther's form and look; thus masked, he passes through the flames to Brünnhild. Already robbed by Siegfried of her maidhood, she has lost alike her superhuman strength, and all her runecraft has she made away to Siegfried—who does not use it; she is powerless as any mortal woman, and can only offer lame resistance to the new, audacious wooer; he tears from her the Ring—by which she is now to be wedded to Gunther—, and forces her into the cavern, [306] where he sleeps the night with her, though to her astonishment he lays his sword between them. On the morrow he brings her to the boat, where he lets the real Gunther take his place unnoticed by her side, and transports himself in a trice to the Gibichenburg through power of the Tarnhelm. Gunther reaches his home along the Rhine, with Brünnhild following him in downcast silence: Siegfried, at Gudrun's side, and Hagen receive the voyagers.—Brünnhild is aghast when she beholds Siegfried as Gudrun's husband: his cold civility to her amazes her; as he motions her back to Gunther, she recognises the Ring on his finger: she suspects the imposture played upon her, and demands the ring, for it belongs not to him, but to Gunther who received it from her: he refuses it. She bids Gunther claim the ring from Siegfried: Guimther is confused, and hesitates. Brünnhild: So it was Siegfried that had the ring from her? Siegfried, recognising the Ring: "From no woman I had it; my right arm won it from the Giant-worm; through it am I the Nibehungen's lord, and to none will I cede its might." Hagen steps between them, and asks Brünnhild if she is certain about the Ring? If it be hers, then Siegfried gained it by deceit, and it can belong to no one but her husband, Gunther. Brünnhild loudly denounces the trick played on her; the most dreadful thirst for vengeance upon Siegfried fills her. She cries to Gunther that he has been duped by Siegfried: "Not to thee—to this man am I wed; he won my favour."—Siegfried charges her with shamelessness: Faithful had he been to his blood-brothership,—his sword he laid between Brünnhilde and himself:—he calls on her to bear him witness.—Purposely, and thinking only of his ruin, she will not understand him.—The clansmen and Gudrun conjure Siegfried to clear himself of the accusation, if he can. Siegfried swears solemn oaths in confirmation of his word. Brünnhild taxes him with perjury: All the oaths he swore to her and Gunther, has he broken: now he forswears himself, to lend corroboration to a lie. Everyone is in the utmost commotion. Siegfried calls Gunther to [307] stop his wife from shamefully slandering her own and husband's honour: he withdraws with Gudrun to the inner hall.—Gunther, in deepest shame and terrible dejection, has seated himself at the side, with hidden face: Brünnhild, racked by the horrors of an inner storm, is approached by Hagen. He offers himself as venger of her honour: she mocks him, as powerless to cope with Siegfried: One look from his glittering eye, which shone upon her even through that mask, would scatter Hagen's courage. Hagen: He well knows Siegfried's awful strength, but she will tell him how he may be vanquished? So she who once had hallowed Siegfried, and armed him by mysterious spells against all wounding, now counsels Hagen to attack him from behind; for, knowing that the hero ne'er would turn his back upon the foe, she had left it from the blessing.—Gunther must be made a party to the plot. They call upon him to avenge his honour: Brünnhild covers him with reproaches for his cowardice and trickery; Gunther admits his fault, and the necessity of ending his shame by Siegfried's death; but he shrinks from committing a breach of blood-brotherhood. Brünnhild bitterly taunts him: What crimes have not been wreaked on her? Hagen inflames him by the prospect of gaining the Nibelung's Ring, which Siegfried certainly will never part with until death. Gunther consents; Hagen proposes a hunt for the morrow, when Siegfried shall be set upon, and perhaps his murder even concealed from Gudrun; for Gunther was concerned for her sake: Brünnhilde's lust-of-vengeance is sharpened by her jealousy of Gudrun. So Siegfried's murder is decided by the three.—Siegfried and Gudrun, festally attired, appear in the hall, and bid them to the sacrificial rites and wedding ceremony. The conspirators feigningly obey: Siegfried and Gudrun rejoice at the show of peace restored.

Next morning Siegfried strays into a lonely gully by the Rhine, in pursuit of quarry. Three mermaids dart up from the stream: they are soothsaying Daughters of the waters' bed, whence Alberich once had snatched the gleaming [308] Rhine-gold to smite from it the fateful Ring: the curse and power of that Ring would be destroyed, were it regiven to the waters, and thus resolved into its pure original element. The Daughters hanker for the Ring, and beg it of Siegfried, who refuses it. (Guiltless, he has taken the guilt of the Gods upon him, and atones their wrong through his defiance, his self-dependence.) They prophesy evil, and tell him of the curse attaching to the ring: Let him cast it in the river, or he must die to-day. Siegfried: "Ye glibtongued women shall not cheat me of my might: the curse and your threats I count not worth a hair. What my courage bids me, is my being's law; and what I do of mine own mind, so is it set for me to do: call ye this curse or blessing, it I obey and strive not counter to my strength." The three Daughters: "Wouldst thou outvie the Gods?" Siegfried: "Shew me the chance of mastering the Gods, and I must work my main to vanquish them. I know three wiser women than you three; they wot where once the Gods will strive in bitter fearing. Well for the Gods, if they take heed that then I battle with them. So laugh I at your threats: the ring stays mine, and thus I cast my life behind me." (He lifts a clod of earth, and hurls it backwards over his head.)—The Daughters scoff at Siegfried, who weens himself as strong and wise as he is blind and bond-slave. "Oaths has he broken, and knows it not: a boon far higher than the Ring he's lost, and knows it not: runes and spells were taught to him, and he's forgot them. Fare thee well, Siegfried! A lordly wife we know; e'en to-day will she possess the Ring, when thou art slaughtered. To her! She'll lend us better hearing."—Siegfried, laughing, gazes after them as they move away singing. He shouts: "To Gudrun were I not true, one of you three had ensnared me!" He hears his hunting-comrades drawing nearer, and winds his horn: the huntsmen—Gunther and Hagen at their head—assemble round Siegfried. The midday meal is eaten: Siegfried, in the highest spirits, mocks at his own unfruitful chase: But water-game had come his way, for whose capture he was [309] not equipped, alack! or he'd have brought his comrades three wild water-birds that told him he must die to-day. Hagen takes up the jest, as they drink: Does he really know the song and speech of birds, then?—Gunther is sad and silent Siegfried seeks to enliven him, and sings him songs about his youth: his adventure with Mime, the slaying of the Worm, and how he came to understand bird-language. The train of recollection brings him back the counsel of the birds to seek Brünnhilde, who was fated for him; how he stormed the flaming rock and wakened Brünnhild. Remembrance rises more and more distinct. Two ravens suddenly fly past his head. Hagen interrupts him: "What do these ravens tell thee?" Siegfried springs to his feet. Hagen: "I rede them; they haste to herald thee to Wotan." He hurls his spear at Siegfried's back. Gunther, guessing from Siegfried's tale the true connection of the inexplicable scene with Brünnhilde, and suddenly divining Siegfried's innocence, had thrown himself on Hagen's arm to rescue Siegfried, but without being able to stay the blow. Siegfried raises his shield, to crush Hagen with it; his strength fails him, and he falls of a heap. Hagen has departed; Gunther and the clansmen stand round Siegfried, in sympathetic awe; he lifts his shining eyes once more: "Brünnhild, Brünnhild! Radiant child of Wotan! How dazzling bright I see thee nearing me! With holy smile thou saddlest thy horse, that paces through the air dew-dripping: to me thou steer'st its course; here is there Lot to choose (Wal zu küren)! Happy me thou chos'st for husband, now lead me to Walhall, that in honour of all heroes I may drink All-father's mead, pledged me by thee, thou shining Wish-maid! Brünnhild, Brünnhild! Greeting!" He dies. The men uplift the corpse upon his shield, and solemnly bear it over the rocky heights, Gunther in front.

In the Hall of the Gibichungs, whose forecourt extends at the back to the bank of the Rhine, the corpse is set down: Hagen has called out Gudrun; with strident tones he tells her that a savage boar had gored her husband.—Gudrun [310] falls horrified on Siegfried's body: she rates her brother with the murder; Gunther points to Hagen: He was the savage boar, the murderer of Siegfried. Hagen: "So be it; an I have slain him, whom no other dared to, whatso was his is my fair booty. The ring is mine!" Gunther confronts him: "Shameless Elf-son, the ring is mine, assigned to me by Brünnhild: ye all, ye heard it."—Hagen and Gunther fight: Gunther falls. Hagen tries to wrench the Ring from the body,—it lifts its hand aloft in menace; Hagen staggers back, aghast; Gudrun cries aloud in her sorrow;—then Brünnhild enters solemnly: "Cease your laments, your idle rage! Here stands his wife, whom ye all betrayed. My right I claim, for what must be is done!"—Gudrun: "Ah, wicked one! 'Twas thou who brought us ruin." Brünnhild: "Poor soul, have peace! Wert but his wanton: his wife am I, to whom he swore or e'er he saw thee." Gudrun: "Woe's me! Accursed Hagen, what badest thou me, with the drink that filched her husband to me? For now I know that only through the drink did he forget Brünnhilde." Brünnhild: "O he was pure! Ne'er oaths were more loyally held, than by him. No, Hagen has not slain him; for Wotan has he marked him out, to whom I thus conduct him. And I, too, have atoned; pure and free am I: for he, the glorious one alone, o'erpowered me." She directs a pile of logs to be erected on the shore, to burn Siegfried's corpse to ashes: no horse, no vassal shall be sacrificed with him; she alone will give her body in his honour to the Gods. First she takes possession of her heritage; the Tarnhelm shall be burnt with her: the Ring she puts upon her finger. "Thou froward hero, how thou held'st me banned! All my rune-lore I bewrayed to thee, a mortal, and so went widowed of my wisdom; thou usedst it not, thou trustedst in thyself alone: but now that thou must yield it up through death, my knowledge comes to me again, and this Ring's runes I rede. The ur-law's runes, too, know I now, the Norns' old saying! Hear then, ye mighty Gods, your guilt is quit: thank him, the hero, who took your guilt upon him! To mine own hand he gave [311] to end his work: loosed be the Nibelungs' thraldom, the Ring no more shall bind them. Not Alberich shall receive it; no more shall he enslave you, but he himself be free as ye. For to you I make this Ring away, wise sisters of the waters' deep; the fire that burns me, let it cleanse the evil toy; and ye shall melt and keep it harmless, the Rhinegold robbed from you to weld to ill and bondage. One only shall rule, All-father thou in thy glory! As pledge of thine eternal might, this man I bring thee: good welcome give him; he is worth it!"—Midst solemn chants Brünnhilde mounts the pyre to Siegfried's body. Gudrun, broken down with grief, remains bowed over the corpse of Gunther in the foreground. The flames meet across Brünnhild and Siegfried:—suddenly a dazzling light is seen: above the margin of a leaden cloud the light streams up, shewing Brünnhild, armed as Walküre on horse, leading Siegfried by the hand from hence. At like time the waters of the Rhine invade the entrance to the Hall: on their waves the three Water-maids bear away the Ring and Helmet. Hagen dashes after them, to snatch the treasure, as if demented,—the Daughters seize and drag him with them to the deep.

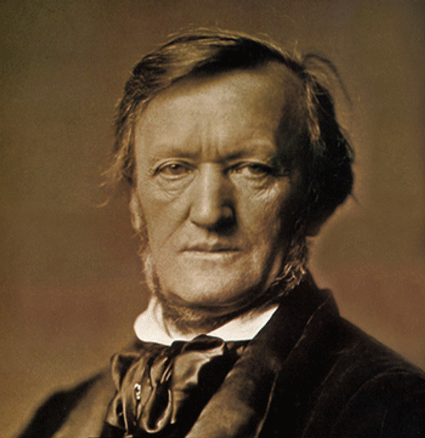

Richard Wagner (1848), as translated by William Ashton Ellis [Richard Wagner's Prose Works, Volume VII, 301–311 (1898)]