Adorno would slightly backtrack in his later work, Negative Dialects, where he suggested it might have been wrong to

say that after Auschwitz you could no longer write poetry - though he would

become even more damning about the colossal existential terror of the guilt

and insanity of its horrors. Adorno’s vision for the survivors of events

such as the Holocaust is almost Kafkaesque; but, one might equally argue

that Paul Celan’s poem Todesfuge says everything that needs to be

said about war and its horror.

Composers who lived through the war have tended, like Adorno, and even the

Romanian-born poet Celan (who wrote largely in German) to focus on the

victims of Nazi oppression: Schoenberg’s A Survivor from Warsaw or

Nono’s Ricorda cosi ti hanno fatto in Auschwitz are just a couple

of notable examples. Where composers have taken a view on allied

destruction elsewhere they have particularly centred on Japan and the

nuclear cataclysm: Penderecki’sThrenody to the Victims of Hiroshima and Nono’s Canti di vita e d’amore: sul ponte di Hiroshima. Only the

openly-pacifist Benjamin Britten in his War Requiem could be said

to have taken an entirely universal (though hardly neutral) position on the

pointlessness of war. Richard Strauss, who in Metamorphosen, and

even the Vier Letze Lieder, wrote music which came closer to

elegy, music that looked back into the past through the ruins of the

present. Most German composers have rather avoided tackling the subject of

the destruction of their own cities altogether, perhaps because the subject

is too raw to address.

Dresden was, and remains, one of the clearest examples of a German city

ruined in the same way as the cities which drew in Britten, Penderecki and

Nono - widely accepted today to have been at least indiscriminate, and

probably questionable. Historically, its relationship with music is almost

as old as European classical music itself, though after the war, the

anniversary of its destruction, remembered on a single day, has been

closely defined by an Italian requiem - Verdi’s.

Identification in music for reviewers can be related to the circumstances

of our birth as much as it is to the objectivity of the performances before

us. Striking that balance can sometimes be problematic, however. Questions

of guilt, responsibility - and even Adorno’s premise that one is somehow

corroding the very basis of atonement - can make one extremely wary of even

approaching such a review in the first place. But with a German ancestry -

and connections to Dresden - I wanted to hear and write about Christian

Thielemann’s new recording of Verdi’s Requiem from the distance of

time - and the commemoration of the destruction of this great city -

remembered each year in its annual concert.

Thielemann’s concert of the Requiem is not in itself a one-off

performance. Since 1951, starting with Rudolf Kempe, the Dresden

Staatskapelle and chorus of the Staatsoper has given a concert of Verdi’s Requiem on the 13th February every year on Dresden

Memorial Day - although in recent years a different work has often been

played. (I recall a Missa Solemnis, this year it was Dvořák’sStabat Mater and in 2020 it will be Purcell’s Funeral Music for Queen Mary and Mahler’s Tenth.) It has

mostly been the case that these concerts have been played on three nights -

two in the Semperoper, and one in the Frauenkirch. The occasion is marked

by reconciliation and tolerance, of shared hope and peace. Those first

performances under Kempe were played in the shattered Staatstheater - and

the destruction of the city, the memories of the apocalypse of the

firestorm which had swept through it were still fresh - much as they were

for much of mainland Europe and the major cities of Japan and the Far East

at the time. The performances then - as they are now - are premised on

coexistence and not division, on healing and not the wounds of war. Even

when you return to Dresden many decades after the events of the Second

World War pockets of the city show scars of its destruction that may never

be entirely erased; but that is equally common if you walk the streets of

Warsaw or Coventry as well.

Although Christian Thielemann is most closely identified as a conductor

from the Germanic tradition, his immersion into Italian repertoire has been

convincing (Otello was performed by him at least as far back as

1996, and the Quattro Pezzi Sacri has often been programmed as

well). Although this Dresden Verdi Requiem is the earliest one by

him I can recall hearing, it is by no means his only one. It’s true that if

you’re looking for anything resembling an overtly ‘Romantically’ phrased

performance with Italianate warmth you probably need to look elsewhere -

though this Dresden Requiem makes considerably more of a statement

than one performed a year later at the Salzburg Festival. There is

undoubtedly a sense of reverence to it - something which at Easter in

Salzburg 2015 had been replaced by something altogether less fragile and

certainly less spiritual.

The Dresden Staatskapelle is no stranger to Verdi’s Requiem -

Sinopoli, in one of his final performances before his death, gave the

Dresden Memorial Concert from the Frauenkirch on 13th February

2001 - a recording which has only ever been issued on a private label.

Christian Thielemann does take a different approach to the work, in part, I

suspect, because the sound of the orchestra can be quite markedly darker

than Sinopoli brought to it - not that he brings much warmth to the Dresden

sound either, especially in the strings which have surprising weight

(Sinopoli, however, has a more lightweight quartet of singers than

Thielemann mustered for this performance). Additionally, in the past there

have been noticeable differences between Profil’s engineering of their CDs

versus the actual broadcasts they have used (Sinopoli’s Ein Heldenleben was virtually ruined by Profil) - but that is

certainly not the case here. The space allowed around the orchestra is

exceptional, the clarity of the playing is crystal clear and there is a

detail and depth to the performance which is faithful to the acoustics of

the Semperoper. Profil haven’t sought to adjust some of the inherent

balance problems between the orchestra and soloists either - if you

sometimes strain to hear Krassimira Stoyanova climb above the orchestra and

choir that’s because she was slightly overwhelmed by both in the

performance. Does this matter? No it doesn’t because although Stoyanova is

still audible at those climaxes it’s what she does with her voice that

matters and there’s a powerful underlying struggle in her phrasing which is

remarkable.

Thielemann’s view of the Requiem is rather similar to Sinopoli’s

in one respect in that both take a dramatic - though that is not to say

operatic - view of this work. There are spiritual overtones (perhaps

undertones would be a better word), but you have to search deeply for them.

Sinopoli is slower at the opening of the ‘Dies Irae’ - those massive

timpani are like rolling thunder; Thielemann sees them more as a shocking,

explosive blast - and it’s rather more terrifying as a result. Some have

criticised Sinopoli for smothering this music, almost choking it, so it

sounds a little underwhelming - but this is not something I particularly

hear in his Dresden Requiem. Thielemann does drive the ‘Dies Irae’

onwards - though, as you might expect from such an experienced Bruckner

conductor, that drive is almost entirely shaped by a singular line of

thinking. It’s easy to fragment the ‘Dies Irae’ - Thielemann doesn’t do

this; the arc in which its span is taken is impressively extended, like a

singular breath that never seems to quite come up for air. This can be

challenging for his soloists - but whether it’s the dark-hued, solid but

monumental ‘Tuba mirum’ of the bass, Georg Zeppenfeld, or the magnificently

rich-toned ‘Ingemisco’ of the tenor, Charles Castronovo, it’s a contrast of

colour that Thielemann achieves as well as the perfect line that never

feels like it’s just stitched together like fragments of the liturgy. The

‘Quid sum miser’ is like a spiral, the mezzo of Marina Prudenskaja such a

beautiful foil to Stoyanova’s soaring soprano. Perhaps the chorus in the

‘Lacrymosa’ sound a touch loud, just occluding the soloists - but as I

suggested earlier this is a performance which gets its strength from the

ambience of its struggle.

There are times you listen to Verdi’s Requiem and everything after

the ‘Dies Irae’ can seem like a slow descent into anti-climax. Sinopoli was

never one to do this - even in the couple of recordings we have of his

which he made outside his Dresden concert - and Thielemann doesn’t either.

There is a change in the pace of the work, though it’s possibly

even harder to keep a good performance on track. I can’t really fault the

way in which Thielemann balances the orchestra and double chorus through

the ‘Sanctus’ - the sense of divisi has remarkable clarity. You

get this, too, in the ‘Agnus Dei’ where Prudenskaja and Stoyanova are in

such perfect harmony with the chorus - the orchestra just weighty and rich

enough so it wraps like a shroud around the voices. If many conductors see

the ‘Libera me’ as a climax to the Requiem, Thielemann views it as

a true coda - not the actual end of it, but the complete summation of

everything that has come before it. If you listen to the power - and

reverence - behind Thielemann’s ‘Libera me’, in the closing bars you could

be listening to the final pages of Bruckner’s Fifth or Eighth Symphonies.

This is, in part, what makes this Verdi Requiem rather special and

unique.

I think this is one of those performances which can stand alongside some of

the great recordings of the past - de Sabata, Cantelli, Giulini - and,

perhaps, Sinopoli in Dresden, too. It’s beautifully sung, conducted and

recorded - I’m not sure you could ask for much more.

Marc Bridle

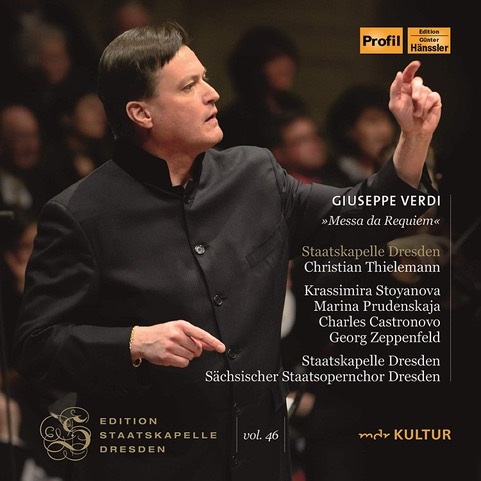

Verdi: Requiem

Krassimira Stoyanova (soprano), Marina Prudenskaja (mezzo), Charles

Castronovo (tenor), Georg Zeppenfeld (bass), Christian Thielemann

(conductor), Staatskapelle Dresden, Dresden State Opera Chorus.

Recorded 13th February 2014 at Semperoper, Dresden.