Famously, the Fourth, if not premiered first, was given the earliest

recording by the New Symphony Orchestra of Tokyo under Hildemaro Konoye in

May 1930; the Eighth was performed in Japan in December 1949, conducted by

Kazuo Yamada, almost certainly the first time it was ever heard in the Far

East.

There is a perfectly logical reason why Japan seems to have been so slow in

embracing western classical music. In part, it is simply a factor of

Japanese society which largely rejected outside cultural influences,

especially before the Meiji Restoration of 1868. But what Japan lacked,

which was not the case in either the United States or Europe, were music

schools and decent orchestras to teach and play this music. Luther Whiting

Mason, director of the Boston Music School, and the Munich-born Klaus

Pringsheim, would both have a profound impact on the expansion of western

music in Japan and its lineage through the twentieth century and onwards

stretches from notable Mahler conductors beginning with Wakasugi, Kazuo

Yamada, Akiyama and Ozawa through to Kobayashi and Inoue and a younger

generation which includes Kazuki Yamada, Kentaro Kawase and Kenshiro

Sakairi.

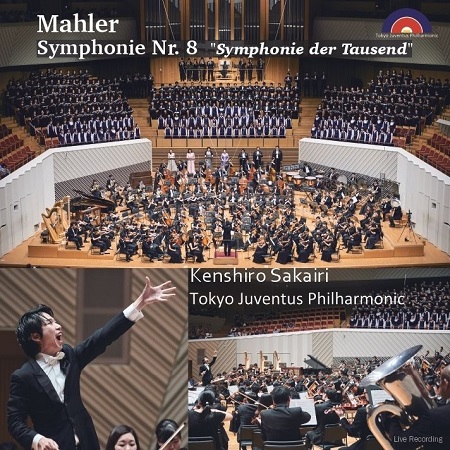

As an introduction to this new recording of Mahler’s Eighth, this diversion

into the (briefest) of backgrounds is not strictly irrelevant because what

we have here are the fruits of those earliest musical schools. The Tokyo

Juventus Philharmonic doesn’t exactly think in terms of repertoire that is

scaled down; in fact, all of its previous CDs have been of some of the most

difficult and unforgiving works which would test many professional symphony

orchestras. But then, this is not an ordinary youth orchestra, and Kenshiro

Sakairi is a distinctly unusual conductor.

The Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic was founded in 2008 - originally under the

name of the Keio University Youth Orchestra - and its first musicians were

mainly high school students and members from the university. Today it has

as many as 150 musicians. Like many western youth orchestras its repertoire

is limited to a few concerts a year but what is particularly distinctive

about the TJP is that it shares many of the characteristics of professional

Japanese orchestras. That blended brass tone, the rich string sound, the

distinctive woodwind phrasing and the precision of the playing are of an

extremely high standard.

If there is a common thread which links youth orchestras it is often that

the body of players is much larger than one would experience in most

symphony orchestras we hear today in concert halls. Eight double-basses are

the norm - not the thirteen we get in this Mahler Eighth. Arguably, the

heft and weight, especially in the strings, probably doesn’t make this

strictly necessary - listen to either recording of Sakairi’s Bruckner

Eighth or Ninth and the richness of the cellos and basses, and even the

violins, sometimes a weakness in many Japanese orchestras, makes for a

thrilling sound, and would likely be so without the added strings. Sakairi

is himself a patient conductor, one who takes his time over the music -

it’s highly organic and is nurtured as such. The pauses and spaces he

inserts between notes, the acknowledgement of bar rests, are more than a

nod to a conductor like Celibidache, or even late Asahina.

It's certainly clear this is a musical partnership which is getting better

- their Mahler Third, recorded in 2017, perhaps got lost in some parts,

where a focus on orchestral beauty became a template for a loss of

perspective elsewhere (though Sakairi is by no means the first conductor to

be trapped by this symphony’s problems). On the other hand, an unreleased

Mahler Second from a year earlier is tremendously powerful for quite the

opposite reason - it sacrifices some orchestral beauty for an unswerving

relentlessness and swagger. A Bruckner Ninth, from January 2018, is a

colossal performance - it’s visionary, prepared with meticulous attention

to detail, and yet so extraordinarily intense and fresh. This most recent

recording of Mahler’s Eighth is at least as striking.

Although CD issues of Mahler Eighth have become more frequent - and in

Japan there had been eleven prior to this recording - by a strange quirk,

and less than a week after this Sakairi performance, another was given, by

Kazuhiro Koizumi and The Kyushu Symphony Orchestra, and that, too, has just

been released on Fontec. Can you have too much of a good thing? Well, yes

and no. For many years, Takashi Asahina’s Osaka Philharmonic recording,

performed in 1972, was the first and only one available - and it remains to

this day one of the best from Japan. One could question the idiomatic

accuracy of the singing - but what Asahina does with the symphony is often

compelling. Yamada’s 1979 recording with the Tokyo Metropolitan Symphony

Orchestra was done thirty years after his Japanese premiere of the work -

and is the most detailed, perhaps most convincing performance to date.

Others, like Wakasugi (who recorded the first complete Mahler cycle in

Japan), Inoue and Kobayashi seem both overwhelmed and lost in the scale of

this symphony. Of the two western conductors to have recorded with Japanese

orchestras, Bertini has a narrow edge over Inbal.

Kenshiro Sakairi’s recording is incredibly detailed; in fact, it’s

meticulously so in a way almost very few Mahler Eighth’s are. This

orchestra and conductor’s precision - in the sense that every note is in

place, the feeling that every facet of the score has been followed - works

for and against them. When I first listened to this CD I was so blown away

by the orchestra, their tone, the finesse and articulation of the woodwind,

and the sheer opulence of the sound generated that the measure of the

symphony’s scale rather eluded me. It’s only on a second listening I became

fully aware of the electrifying performance that Sakairi gives. Quite how

this would have worked in the concert from which this performance is taken

is a question I have yet to definitively answer for myself.

As is common with most of the TJP/Sakairi recordings - most notably the

superlative Bruckner Ninth - it is the singularity of the symphonic line,

the ability to take this music in an arc which is so hugely impressive. I

don’t think Sakairi takes his cue from many of the Japanese performances he

probably grew up with - rather, the influence that seems most striking is

that of Bernstein. He is only marginally slower than Bernstein’s LSO

recording, though timings are deceptive. The pace Sakairi sets - and

generally holds - is swift but the structure, whether in Part I or Part II,

retains a formidable flow and smoothness, and I don’t mean smoothness in an

ineffectual or unimposing way. The clarity of the variations in Part II,

where many conductors sectionalise this symphony, isn’t patched together -

it has a very fluid narrative. And if this is an orchestra with a powerful

sound, the whole of the opening of Part II, that wonderfully mysterious

orchestral prelude, is actually magical and haunting. There is much in this

performance which suggests collision - but there is much which swings the

opposite way towards heavenly enlightenment.

How far the pathos, or spirit of redemption, or even the profoundly complex

journey into Faust’s soul, which is a powerful force in this symphony

could, or might, confound a young orchestra or conductor, throws up some

interesting contrasts with other recordings. Sakairi is barely over thirty;

Asahina and Yamada were well into their sixties when their recordings were

made. Few might expect a younger man to empathise so directly with the

concept of mystery - yet, it’s here. It was there in his Bruckner Ninth.

Yamada’s recording might be convincing in many respects, but it’s arguable

thirty years after his premiere his vision of this symphony had changed. As

was common with many Yamada performances in his later years, tempo could be

wildly disjointed, and that is the case here. He speeds up, and slows down,

with disturbing frequency. Asahina is perhaps more stable. But what

disfigures both performances is the quality of the playing, which is

erratic at best, and simply inferior at worst. Asahina is prone to take his

time; Yamada tends to navigate a more ill-disciplined route.

Sakairi and the TJP play with quite sublime brilliance, and the recording

exposes them to quite a high degree of scrutiny. As is common with many

Altus CDs, the engineering is first rate - though perhaps some might find

the choral forces a little recessed. The focus here can sometimes be very

much on the orchestra and the soloists. That ‘exposure’ works in many ways:

the orchestra can sound unusually dark (though I personally like their

sound), the tendency to spotlight instrumental solos is often ravishing.

The opening to the ‘Chorus Mysticus’ is astounding, mystical, hushed and

deeply moving. How the chorus just floats above the orchestra and the

soprano gently rises through them both is beautifully captured by the

microphones. But to be able to not overblow the climax as well says much

for both the careful attention to dynamics from Sakairi and the outstanding

engineering.

What of the singing itself? It’s undoubtedly the case that in the past

Japanese choirs and soloists have found German a problem; that is less true

today. Most, if not all, of the singing on this Mahler Eighth is

comfortably pronounced, and more so given the heady tempo which Sakairi

sets for them. Is there enough contrast in the soloists? Yes, I think there

is, especially in the trio of sopranos who sing with gorgeous precision and

colour. Shimizu Nayutu, as Pater Profundis, is superb - a deep, rich bass,

sounding suitably tortured. Likewise, Miyazato Naoki manages the high

tessitura of Doctor Marianus with flawless technique. Both the NHK

Children’s Choir and the Tokyo Juventus Philharmonic Choir are superb.

This is unquestionably the finest Mahler Eighth yet to emerge from Japan.

However, I’d go a bit further than this - it leaves a lot of Mahler Eighths

recorded in the United States and Europe rather in the shade as well. There

is a blend of the orchestral and the vocal here, the redemptive and the

dramatic, which is enormously compelling. It helps it has been captured in

beautiful sound, but the performance is entirely gripping. Much of it is

simply electrifying - many Mahler Eighths, rather elusively, aren’t. All in

all, a magnificent disc.

Marc Bridle

Soprano 1 (Moritani Mari), Soprano 2 (Nakae Saki), Soprano 3 (Nakayama

Miki), Alto 1 (Akira Taniji Akiko), Alto 2 (Nakajima Keiko), Tenor

(Miyazato Naoki), Baritone (Imai Shunsuke), Bass (Shimizu Nayuta), NHK

Tokyo Children's Choir (Choral Conductor: Kanada Noriko), Tokyo Juventus

Philharmonic Choir (Choral Conductor: Tanimoto Yoshi Motohiro, Yoshida

Hiroshi)