When it premiered at the Houston Grand Opera in 1987, just a decade and a

half after the epochal events it portrays, Nixon in China received

accolades. Since then, it has secured a modest spot in opera world, with

two or three productions a year worldwide – but this understates its

musical significance. Over the past three decades, other composers have

adopted many of Adams’ innovative techniques, such as basing plots on

current events, using romantic harmonies and melodies, quoting popular

music, including surrealistic political satire, and amplifying singers.

Poet Alice Goodman did not write the libretto around a conventional plot.

Instead, she recounts the ceremonial highlights of President Nixon’s

famous visit – his arrival at Beijing Airport, meetings with the

Chinese leaders, Pat Nixon’s experiences among the people, a state

banquet, and a revolutionary ballet – as a basis for a surreal

reflection on the tension between public duty and private life.

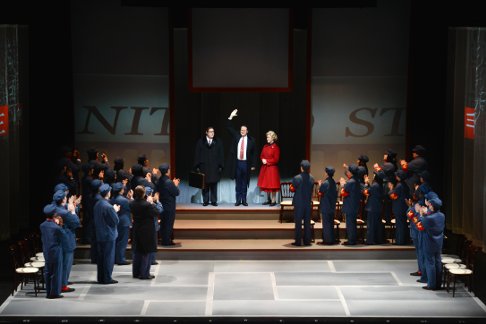

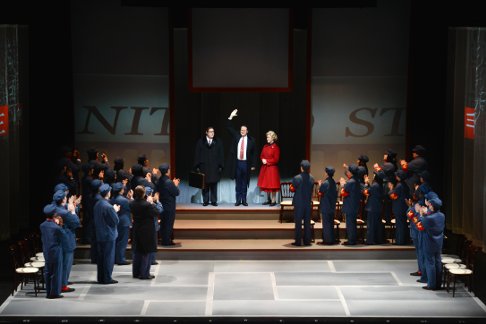

The Nixons and ensemble

The Nixons and ensemble

The libretto’s strength lies in a series of introspective monologues

in which each character recounts important memories that shape their

attitude toward politics. Goodman’s underlying point seems to be that

most politicians are childishly self-important. So Madame Mao is a

revolutionary fanatic who treats the creation of a perfect society as an

aesthetic project. Kissinger is a doddering old fool who responds to Chou

En-Lai’s desire for dialogue by asking to go to the toilet. President

Nixon is an American provincial who obsesses on World War II. Mao is a

cryptic old man muttering platitudes about his boyhood revolutionary

achievements. All have lost touch with everyday virtues of family,

community and humanity.

The remaining two characters offer a more sympathetic and humanistic

alternative. Chou En-Lai’s elegance and sense of the historical

moment fuel two memorable arias, one each at the end of the first and third

acts. Pat Nixon expresses stereotypical virtues of “home and

hearth” through her simple love of children, animals, community and

other simple things.

Adams sets this libretto with a distinctive style of orchestral writing.

Drawing on the minimalist tradition of Philip Glass and others, the score

of Nixon in China rests on hypnotically oscillating block chords

and arpeggios punctuated by syncopated notes. The challenge for minimalist

music is that it lacks a clear architectural principle that allows music to

develop harmonically and melodically over longer timespans. Climaxes are

achieved almost entirely by increasing volume or speed. Minimalist music

shimmers and even changes, but it does not evolve – in contrast to

the music of Schubert, Wagner, Bruckner and other traditional composers who

sometimes employed repetitive forms.

Ballet sequence

Ballet sequence

For Adams, the overall result is atmospheric but static music, more akin to

a film score than a classic opera. In most scenes of Nixon in China, that mood is one of slightly mysterious

introspection, as if one is seeking to remember something distant and

ineffable – a suitable style for moments when characters reminisce.

The result can be quite beautiful, as in Pat Nixon’s scena

“This is Prophetic,” with its hypnotically undulating

alternating between E major and E minor. It can also be exciting for short

periods, as in Madame Mao’s robotic revolutionary rhetoric. Yet it

rarely sweeps the listener up.

In contrast to previous minimalists, Adams seeks to offset the orchestral

stasis by introducing traditional melody in the vocal parts – which

he does by adopting a surprising number of traditional bel canto

conventions. Act I ends with an ensemble, Act II with a coloratura

showpiece, and Act III with a reverie – and the opera even contains a

ballet, albeit a surrealistic one reminiscent of a 1950s movie dream

sequence. Each major character receives at least one big scena.

President Nixon’s opening aria (“News”) follows the

fragmented style of the orchestra, but in the second and third acts, the

vocal lines become longer and more romantic – and are then often

picked up by the orchestra in a manner intermittently reminiscent of Wagner

or Puccini. Later in the opera, pop rhythms and ballet music appear.

This distinctive structure means that a successful performance of Nixon in China requires great singing actors. The justly

celebrated premiere production, directed by Peter Sellars and featuring

Boston-area stalwarts Janes Maddalena as President Nixon and Sanford Sylvan

as Premier Chou En-lai, was exemplary. It also included a superb portrayal

of Pat Nixon by the extraordinarily versatile crossover artist Carolann

Page – who teaches today at Westminster College, less than a mile

from where Princeton Festival performs.

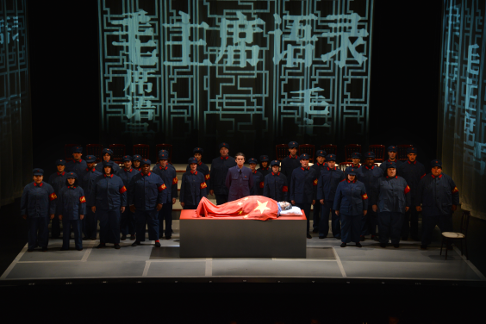

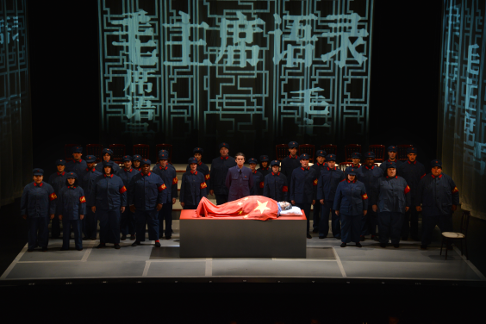

Death of Mao

Death of Mao

The Princeton cast was comprised of younger American singers with a solid

track record in regional houses and on the competition circuit. Almost all

excelled in what was the first time performing this difficult score.

Baritone Sean Anderson, who has performed here several times before,

blustered self-importantly as Nixon. Lighter baritone John Viscardi

remained dignified and smooth in the lighter role of Chou En-lai.

Coloratura Soprano Rainelle Krause reined in a few blaring high notes to

offer a subtly characterized renditions of Pat Nixon’s big monologue.

Soprano Teresa Castillo brought down the house with Madame Mao’s big

rant, even if she lacks some of the icy precision and focus the score

suggests. Tenor Cameron Schutza deployed a ringing Heldentenor to portray

Chairman Mao. Baritone Joseph Barron was gruffly sonorous as Henry

Kissinger. Each singer was precise and passionate and acted well.

A great performance of this difficult opera, however, requires more.

Maximum impact requires singers able to deliver lines with the subtlety,

exceptionally clear diction and clear and beautiful tone of a Lieder singer

– something made easier by the use of microphones authorized by the

composer. In general, the Princeton performance was more conventionally

“operatic” that it might have been, and not all singers

consistently attended to stylistic nuances.

One example must suffice. Unlike many modern composers, Adams writes with

exceptional attention to poetic cadence. The note values in his vocal lines

subtly mirror different patterns of long and short syllables. In

particular, the ends of many lines are syncopated (most often

LONG-short-LONG, or LONG-short-short). (An example is President

Nixon’s first sung line: “News has a kind of MY-ster-Y”.)

This distinctive three-syllable rhythmic snap drives the music forward

– much as does the rap cadence in a more recent work like Hamilton.

Such details intermittently went missing, as one might expect in a short

run. Achieving such stylistic unity requires, in addition to precise

coaching, a conductor who keeps the orchestra moving swiftly and is willing

to hold down the volume and weight of the instrumental playing. Festival

Director Richard Tang Yuk directed with his customary care and precision,

and the orchestra and chorus delivered a polished performance of this

difficult work – even if cautious tempos, a thick sound, and

intermittent lack of rhythmic nuance tended, in the end, to drag the

performance down somewhat. The staging showed that much how much innovative

lighting and color can achieve at a relatively low cost. The opening and

closing scene, in which Chou stands before the casket of Mao, was

particularly effective. The ballet dancers were engaging.

Overall, this production reinforces the Princeton Festival’s

reputation as a site for innovative and sophisticated summer opera.

Andrew Moravcsik

![The Nixons and Kissinger [Photo courtesy of The Princeton Festival]](http://www.operatoday.com/NiC003.png)