Sometime after Goldschmidt’s death, I found a trove of his recordings and those by other modern composers in a small local Oxfam. I bought as much as I could afford but told everyone. Suddenly, someone with more money than me swooped them all up. Later, talking to the composer Kalevi Aho, we deduced that the 200 or so CDs must have belonged to Goldschmidt himself since all the other composers were connected to his personal circle of associates. It may have been the clearance of his estate. Luckily, I did manage to grab what might have been Goldschmidt’s own copy of Beatrice Cenci, with Lothar Zagrosek conducting the Deutsches-symphonie Orchestra, Berlin, from the world premiere in August 1994, when Ian Bostridge sang the small part of the Page at the Villa Cenci orgy.

Goldschmidt’s Beatrice Cenci recounts a real-life scandal. Count Francesco Cenci, a renaissance nobleman, was fabulously rich, but violent. Because he was so powerful, he got away with raping his teenage daughter, Beatrice, who was eventually beheaded for killing him. Though Goldschmidt and his librettist based their version on a play by Percy Bysshe Shelley, the story is universal, and sadly, all too relevant to our times. Too much can be made of Goldschmidt’s connections with Weimar Germany, from which he emigrated aged only 33. He spent the next 60 years of his life in Britain. Beatrice Cenci is a work of its time, written for the 1951 Festival of Britain, when the concept of courage against injustice was recent memory. Goldschmidt maintained that his music was not programmatic but rooted in relationships with people and was particularly sensitive to the way that women were treated in patriarchal societies. “My works”, he wrote “have always come about as an interchange with the feminine in all its facets. That is the aura in which I compose”.

In Goldschmidt’s Beatrice Cenci, Count Cenci’s arrogant sense of entitlement is compounded by all around him, from his servants to the Courts and to the Papacy. The introduction is brief, but magnificent, but as anyone familiar with Schreker and Zemlinsky, Goldschmidt’s predecessors, will know, lush does not mean romantic. Almost immediately, sharp, tense chords intervene. Lucrezia’s (Dshamilja Kaiser) lines are shrill, rising high on the register, swooping downwards: an air of unsettled alarm. She’s Count Francesco’s second wife, not Beatrice’s mother, but she knows he’s a tyrant, and that wrong. Beatrice (sung by Gal James) at this stage has softer, less assertive tones. Bernardo (Cristina Bock), Beatrice’s full brother, is also cowed, burying his head on Beatrce’s lap. “Ours is an evil lot, and yet” sings Beatrice “let us make the most of it”. The cry of abused children, everywhere.

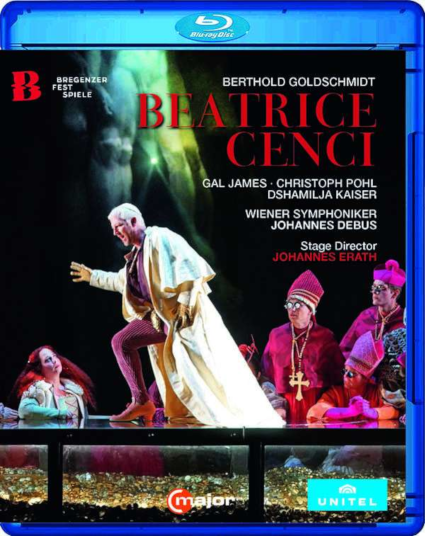

Enter Cardinal Camillo, (Per Bach Nissen) whose lines swagger, rolling figures built into the part, coiling like a snake. He’s covered up a murder for Cenci (sung by Christoph Pohl), both complicit in evil. Pohl’s baritone smoulders yet has a lethal edge: the character’s nasty business. Beatrice places her hopes in Orsino (Michael Laurenz) a young priest – forbidden territory! He’s in love with her, so offers to help her. At the Villa Cenci, princes and cardinals are replete after an orgy. Cenci sings “I too am flesh and blood and not a monster, as some would have me”. Yet he proudly announces that he’s killed all his sons. One was killed when a church collapsed on him, another knifed by a stranger, but Cenci’s not bothered. More wine, he calls, and blasphemes. Even Cardinal Camillo says Cenci’s insane, but Cenci threatens him, too. Now Beatrice takes courage, passionately begging the guests to save her from the palace. But Cenci isn’t scared. In a slithering tone he attempts to rape her again.

During the interlude, the open-air stage at Bregenz is filmed, darkness lit by sudden flashes of light – hiding yet alluding to the unspeakable. Lucrezia finds Beatrice, who has gone mad, cradling a doll. “I have endured a wrong so great that neither life nor death can give me rest – ask not what it is”. The voices of stepdaughter and stepmother intertwine, suggesting other unspoken horrors (Lucrezia’s quite young – the many adult children are not hers.) Beatrice talks Orsini into hiring hit men, to free Beatrice from her father. Count Cenci returns, but Lucrezia bars his way. On the Bregenz stage, Cenci wears a diamante penis, big enough that the audience far from the stage get an eyeful. Quietly, Lucrezia slips poison into his wine, and he falls asleep. The hit men come but their job is done, and they throw the body down a wall. Suddenly, Cardinal Camillo returns, surrounded by troops with a warrant for Cenci’s arrest. Concluding that Cenci was killed by Lucrezia and Beatrice, he has them taken off to prison.

Tolling bells introduce the final act. Bernardo and Beatrice are huddled together, Lucrezia with them. The henchmen Orsini hired give witness against Lucrezia, but Beatrice refuses to deny what has happened. “Say what you will, I shall deny no more”. From this point, Goldschmidt’s opera becomes more abstract, more “modern”, psychologically true rather than literal. A distant choir is heard. Cardinal Camillo says that the Pope has denied mercy. The sentence is death. Against the mysterious strains of an orchestral Nocturne, Lucrezia and Beatrice are seen, both crumpled like broken dolls. Beatrice now gets a chance to sing a “mad scene”, which is more poignant than deranged. “Sweet sleep were like death to me…O Welt, Lebewohl”, her words echoed by the orchestra.

A short but dramatic Zwischenspiel introduces the final scene. Carpenters are erecting a scaffold, the orchestra imitating their ferocious blows. An angry crowd gathers, and Lucrezia’s clothes get ripped off (she’s wearing a body suit, for the faint-hearted). Yet Beatrice is strangely calm. “Be constant to the faith that I though wrapped in the clouds of crime and shame lived forever holy and unstained”. Those who want blood and guts will be disappointed as the women just fall dead. But Cardinal Camillo is moved. “They have fulfilled their fate, guilty yet not guilty, thus do evil deed bring evil, crimes bring forth crimes”. He blesses them with a quiet Requiem Aeternum.

Bertold Goldschmidt’s opera is wonderfully taut, more chamber opera than regular opera, so I can imagine future productions that make the most of the claustrophobic atmosphere and the liberating release of death at the end, but this DVD – heard together with the often musically superior Lothar Zagrosek recording – should secure Beatrice Cenci its rightful place in modern repertoire.

Anne Ozorio