Instead, Davies and designer Leslie Travers, in their attempt to examine

the sexual politics of Carmen through a contemporary lens,

transfer the action of the opera to the ‘world of Brazilian favelas and the

tight community within’. They cite the Brazilian government’s

implementation, with the assistance of the army, of the favela eradication

in the 1960s - and the poverty, violence and lawlessness that characterised

the favelas - as evidence in support of their argument that this world fits

‘the economic and sexual politics of Carmen’ and is ‘a good home

for Carmen’s wild Bohemian spirit’.

At least, that’s what Davies tells us in a programme booklet article which

I did not read until after the performance. Looking at Travers’ grey,

gritty set - a curving edifice that served, pretty effectively, as run-down

tenement block, soldiers’ barracks, Lillas Pastia’s tavern in the shadow of

the ramparts, mountain-side smugglers’ den, and bull-ring arena - I had no

sense of the ‘visual flavours of Latin America’ that Travers and costume

designer Gabrielle Dalton are reported to have researched.

Ross Ramgobin (Moralès), Anita Watson (Micaëla). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Ross Ramgobin (Moralès), Anita Watson (Micaëla). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Not that it mattered. The opening moments of the production may not have

dazzled our eyes with the oranges and golds, gleaming in the bright white

light, of a square in Seville, but the grimy compound enclosed by metal

grilles, through which the smirking soldiers leered at passing young girls,

and the towering tenements strewn with sagging washing-lines, made for a

persuasive, if indeterminate, locale. As the grilles were swivelled when

the working girls finished their shift at the cigarette factory, we were by

turn both outsiders and insiders, a fitting metaphor for the opera’s

tensions and divisions.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

There was, however, little sense of racial conflict. This Carmen was no

foreigner on Spanish soil, a traveller from lands flung far and wide, who

challenges a society that cannot accept the outsider for fear of denying

itself. Her wildness was not a sort of gypsy madness, rather a wilfulness

born of frustration and a desire for freedom. Fair enough. But, there was

similarly no sense of the class conflicts that oppress Carmen (reflecting

the contemporary tensions between the middle-class and the large, malleable

labour force upon which the bourgeoisie depended in Bizet’s France),

despite Davies’ suggestion that Carmen is a sort of nineteenth-century Jade

Goody, cut from a similar working-class cloth.

If you excise race and class, you’re left with gender and

nineteenth-century cultural ambivalences about women and female sexuality.

Indeed, Davies’ principal aims seems to have been to take a feminist stance

and pose some #MeToo questions in the context of contemporary sexual

politics. But, while she asks, ‘whether Bizet’s ending would be the same,

or any different were he writing today?’, Davies’ production doesn’t

actually venture very far in exploring this question. Some of the spoken

dialogue may have been revised, but since it’s in French this will pass

most of the audience by, unless they glance up at surtitles which are

out-of-kilter with the stage action. Instead, what we have is a

conventional telling of an ‘old’ tale: the silencing of a sexually

confident woman by a society afraid of her liberated spirit.

Dimitri Pittas (Don José), Virginie Verrez (Carmen). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Dimitri Pittas (Don José), Virginie Verrez (Carmen). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Fortunately, Davies has an excellent cast to tell this tale. French

mezzo-soprano Virginie Verrez’ Carmen really does charm and entrance when

she sings, even if her actions and behaviour are often more aggressive than

provocative. Carmen clicks, not castanets, but empty shot glasses; she

douses a soldier in liquor and taunts him with a lighted match, laughing

viciously. Charming. Though more likely to be wielding a Kalashnikov than

castanets, Verrez still seduced: she has a lovely silvery, silky mezzo

which can shine brightly or sink into darker hues, and she moves between

the two with confidence and expressive clarity. Her Habañera fully

exploited the teasing slides of Bizet’s chromaticism but it’s a pity that

Davies doesn’t really acknowledge that this is both song and

dance: the physicality of the song expressed through its vamping rhythm and

extravagant leaps and descents of register was largely absent. During the

‘Seguidilla’, Carmen remained squarely seated on the ground, her hands

tightly bound, though Verrez was able to communicate the physical

slipperiness implied with her voice. At Lillas Pastia’s tavern, Carmen

offers to dance for José alone, but then spends most of the song lounging

on an ugly plastic chair; two dancers are called upon to express the

implied physical dynamics and impulses.

Such numbers are also ‘performances’: we are not sure, when she sings these

‘popular songs’ whether Carmen is expressing herself or adopting a

theatrical persona. Here, Carmen’s songs were not placed ‘in the spotlight’

in this way; even the impact of her first entrance, which is such a

disruptive dramatic force, was diminished as she meandered through the

crowd of girls and soldiers. Despite this, Verrez held our attention and

enchanted our ears throughout; tattooed and pony-tailed, sporting first

dull dungarees and trainers, later a backless floral frock accessorised

with red handbag and stilettos, she might have become the generic ‘Essex

girl’ with whom Davies draws parallels. That she did not speaks much for

Verrez’ technical and expressive assurance.

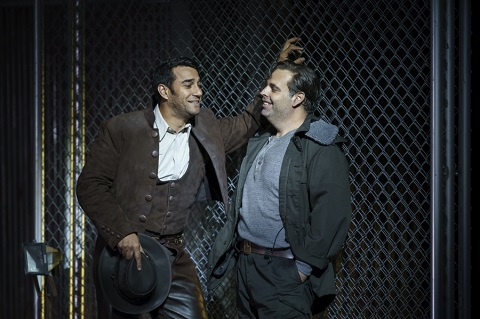

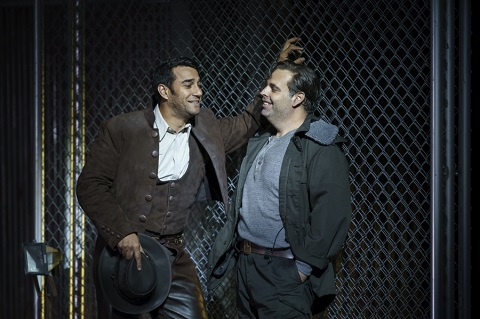

Phillip Rhodes (Escamillo), Dimitri Pittas (Don José). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Phillip Rhodes (Escamillo), Dimitri Pittas (Don José). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Dimitri Pittas’ José is more despondent sulk than bewildered naïf, but

Pittas has the range and power for the part. The mummy’s-boy cadet was

fittingly melancholy and troubled, and, by Act 4, credibly deranged by love

and impotence as he prowled within the crowd outside the bull-ring arena.

Initially, I thought I detected an edgy grain to Pittas’ tenor, when it was

pushed high or loud, and the ‘Flower Song’ didn’t really intoxicate with

its melodic flights of fancy; but, his tenor increasingly found a finer,

warmer focus and, by the climactic duet, rang with dramatic intensity.

Anita Watson was a surprising forthright Micaëla, and it worked: this

Micaëla was much more than a one-dimensional ‘good girl’ - the foil to

Carmen, introduced into the opera to satisfy Bizet’s bourgeois audience.

She was not intimidated by the groping eyes of the soldiers in Act 1,

making her utterances more integrated into the dramatic tension than is

sometimes the case. And, during her Act 3 air, time seemed to stand still:

Watson conveyed Micaëla’s quiet heroism most impressively. This was a

moment of serenity amid the prevailing moral chaos. Phillip Rhodes’

Escamillo wore the toreador’s leather trousers and blouson with style and

displayed the sort of vocal and physical appeal that made Carmen’s

attraction persuasive - though, again, he had to fight his way to

centre-stage through the revellers at Lillas Pastia’s.

Harriet Eyley (Frasquita), Angela Simkin (Mercédès). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

Harriet Eyley (Frasquita), Angela Simkin (Mercédès). Photo credit: Bill Cooper.

The secondary roles were strongly characterised and sung, which served to

create an impression of a ‘real’ community. Frasquita (Harriet Eyley) and

Mercédès (Angela Simkin) were fully involved in the drama, sang with

vibrancy, and were also clearly distinguished characters. The reading of

the cards was a striking moment, no mere divertissement for smugglers and

gypsies with time on their hands. Both her companions’ care for Carmen, and

the veracity of the danger embracing her, were powerfully communicated.

“Death, I saw it, him first, me next, for both of us, death,” Carmen sings,

darkly and slowly. It seemed to me that here, perhaps, was a way to answer

the #MeToo questions Davies’ purports to pose: fated to die, she may still

control when and where? Might not Carmen’s final declaration, “I know that

you are going to kill me; but whether I live or die, no, no, I shall not

give in to you!” and her command, “All right, stab me then, or let me

pass!”, be dramatized as a choice? After all, she sings, “Free she was born

and free she will die!”

Henry Waddington really grabbed one’s attention as Zuniga, while Ross

Ramgobin’s Moralès was a strong dramatic presence in the opening Act.

Benjamin Bevan (Dancaire), Joe Roche (Remendado) and Gregory A Smith (in

the spoken role of Lillas Pastia) enlivened the bandit scenes. The

children’s chorus were superb, raised on the tenement balconies, firing

water-pistols at the marching soldiers, and the Chorus of WNO sang, and

moved, persuasively. Tomáš Hanus drew some fire and spirit from the WNO

Orchestra, balancing the exoticism with a warm Romantic glow.

This was a highly enjoyable evening. No ‘concept’ was needed - or, indeed,

really evident: singers and musicians simply let Carmen’s songs ‘speak’ for

themselves.

Claire Seymour

Carmen - Virginie Verrez, Don José - Dimitri Pittas, Micaëla - Anita

Watson, Escamillo - Phillip Rhodes, Moralès - Ross Ramgobin, Zuniga - Henry

Waddington, Frasquita - Harriet Eyley, Mercédès - Angela Simkin, Dancaire -

Benjamin Bevan, Remendado - Joe Roche, Lillas Pastia - Gregory A Smith,

Dancers (Carmine De Amicis, Josie Sinnadurai); Director - Jo Davies,

Conductor - Tomáš Hanus, Set Designer - Leslie Travers, Costume Designer -

Gabrielle Dalton, Movement Director - Denni Sayers, Assistant

Choreographer/Dance Captain - Carmine De Amicis, Fight Director - Lisa

Connell, Orchestra and Chorus of Welsh National Opera.

Birmingham Hippodrome; Tuesday 5th November 2019.