She immediately set about trying to publish some of her early songs. On 7 th April 1878 Smyth wrote a letter to her mother (which she

later quoted in her 1919 memoir, Impressions That Remained):

‘I went to Breitkopf and Härtel - the music publishers par excellence in

the world. The nephew, who conducts the business, Dr. Hase, I know very

well and he is quite one of the most charming men I ever met. ... Well, he

began by telling me that songs had as a rule a bad sale—but that no

composeress had ever succeeded, barring Frau [Clara] Schumann and Fräulein

[Fanny] Mendelssohn, whose songs had been published together with those of

their husband and brother respectively. He told me that a certain Frau

[Josephine] Lang had written some really very good songs, but they had no

sale. I played him mine … and he expressed himself very willing to take the

risk and print them. But would you believe it, having listened to all he

said about women composers, and considering how difficult it is to bargain

with an acquaintance, I asked no fee!’

It’s worth noting that the said ‘Dr. Hase’ advised that the reason that

songs by Fanny Mendelssohn and Clara Schumann had been published was that

they had been included in volumes of songs by the celebrated male composers

to whom they were related, as sister and wife respectively. It was not to

be until 1886 that Smyth succeeded in persuading a music publisher, C.F.

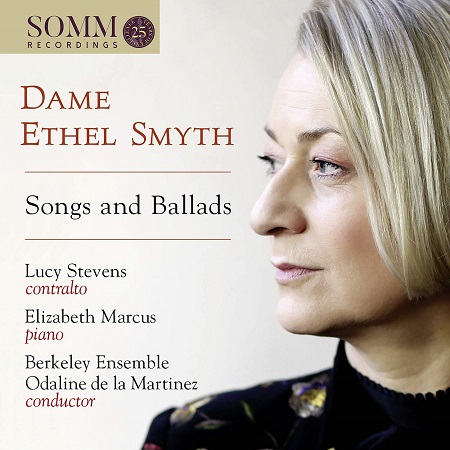

Peters of Leipzig, to publish her songs. This SOMM disc presents her Op.3

and Op.4 sets, published that year but composed long before, theFour Songs for Chamber Orchestra (1908) and the Three Songs (1913).

One of the interesting suggestions made by Chris Wiley and Lucy Stevens in

their liner notes is that the song collections are ‘cycles’, a slippery

term which in her Grove article Susan Youens defines as ‘A group of

individually complete songs designed as a unit […] for solo or ensemble

voices with or without instrumental accompaniment’. Youens goes on to

explain that: ‘The coherence regarded as a necessary attribute of song

cycles may derive from the text (a single poet; a story line; a central

theme or topic such as love or nature; a unifying mood; poetic form or

genre, as in a sonnet or ballad cycle) or from musical procedures (tonal

schemes; recurring motifs, passages or entire songs; formal structures);

these features may appear singly or in combination.’

So, it is suggested that the Op.3 Songs and Ballads are infused

with imagery of the natural world; that the Op.4 Lieder, dedicated

to Smyth’s mother, feature ‘motherhood [as] as recurring theme; that the

1913 Three Songs are informed by Smyth’s suffragette activity, and

‘have the theme of freedom, both personal and political’. Wiley and Stevens

also cites scholar Cornelia Bartsch’s observation: ‘When publishing her

songs, Smyth seemed to acknowledge the notion of unification. In terms of

poetic imagery as well as musically her songs from a unit: they may even be

understood as a cycle, reflecting a self-narrative similar to that convey

in her memoirs more than twenty years later’.

[1]

I’m not so sure. It’s hard to pin down a unified ‘voice’ in these songs.

There’s more a sense of exploration, adaptation, pragmatism, perhaps

opportunism. The French texts (three by Henri de Régnier and one by Leconte

di Lisle) of the four instrumental songs that open the disc, in which the

voice is accompanied by flute, string trio, harp and percussion, seem to

have inspired a certain ‘impressionistic quality’ - oscillating harps and

‘oriental’ flute gestures combined with neoclassical composure from the

strings, and with an added dash of Spanish flair in the ‘Anacreontic Ode’ -

that perhaps led Debussy to describe them as ‘tout à fait remarquables’.

Indeed, as Debussy suggests, there is much to enjoy here, and in this

recording Smyth’s music makes a direct and sincere impact. The Op.3 Lieder und Balladen are dedicated to Livia Frege - friend,

interpreter and dedicatee of the Schumanns and Mendelssohns - and are

recorded here for the first time. The choice of texts - a folksong, three

poems by Joseph von Eichendorff and one by Eduard Mörike - and the imagery

(drawn from the natural world) and emotional contexts (essentially, lost

love), place the songs firmly within the German lied tradition.

I’ve not heard either contralto Lucy Stevens or pianist Elizabeth Marcus

perform before, live or on recording. Stevens, the notes inform me, studied

voice with Gerald Wragg at the Royal Welsh College of Music & Drama,

after acting studies at rose Bruford College; Marcus is a Fellow at the

Guildhall School of Music. Together they convey a responsiveness to Smyth’s

musico-poetic sensibility.

Stevens has a pleasing, easeful and well-centred middle and lower range but

can sound a little tense, and sometimes thin, when she ventures higher. I’d

also like more pristine diction, though it’s good that texts and

translations are provided. The tenderness and folk-like simplicity of the

first of the Op.3 songs, ‘On the Hill’, is occasionally marred by a

slightly fraught and wide vibrato when the vocal line rises. Marcus, a

prize-winning harpsichordist, shapes the left-hand in ‘The Lost Hunter’

most sensitively, whether in octaves with the vocal line or representing

the speaker’s heart as it rumbles “full of woe”, or the trees as they

rustle and the upwelling of the poet-speaker’s emotion: “What awe does

swell my breast!” The accompaniment forms a winning narrative and

repeatedly Marcus draws forth the details of Smyth’s responses to literary

expression and imagery most perceptively. Stevens finds the more

introspective and gentle emotional terrain of songs such as ‘Near the

Linden Tree’ and the rather contemplative and sombre ‘It changes what we’re

seeing’ more comfortable. The more complex narrative of the longer song,

‘Fair Rohtraut’, is thoughtfully shaped, though the dynamism and

exhilaration of the hunt, enhanced by the closeness of hunter and beloved,

and by the use of direct speech, is not fully exploited.

The Op.4 Lieder begin with ‘Tanzlied’ (Dance Song), a setting of

text drawn from Georg Büchner’s political satire Leonce und Lena,

in which Rosetta, Prince Leonce’s mistress, addresses the fragmented parts

of her own body: “O my poor tired feet, you have to dance/In multi-coloured

shoes”, “O my hot cheeks you have to glow/From wild caresses.” Marcus

captures the rather brittle and sparse quality of the ‘waltz’, though one

feels that both piano and voice might more emphatically convey the strange

disorientation created by both the textual imagery and rhythmic asymmetry.

The plummet in the piano postlude at the close feels as if it should be

darker and more disturbing than it is here.

‘Schlummerlied’ (Lullaby) has a lovely Brahmsian lilt and bitter-sweetness,

with both chromatic nuances in the vocal line and harmonic wanderings

discerningly emphasised. The abstract wondering of ‘Mittagsruh’ (Midday

Rest) seems to demand greater intensity than the performers inject here.

Two settings of Klaus Groth complete the set: ‘Nachtreiter’ (The Night

Rider) again requires greater vocal weight, intensity and range of colour

than Stevens can summon, but in ‘Nachtgedanken’ (Night Thoughts) there is a

fitting restlessness which builds to the central image: “Es wird mein

Bette/ Dem Kampf zur Wiege,/ Dem Kriege,/ Dem bösen Kriege/ Zur friedlosen

Stätte.” (My bed is becoming/ The cradle of struggle, The peaceless site of

war/ Of evil war.) Again, Marcus’ contribution to the dramatic narrative is

considerable.

The Op.13 songs were among many of Smyth’s works from the 1910-14 that

contained autobiographical and/or political elements. ‘Possession’ was

dedicated to Emmeline Pankhurst, ‘On the Road: A Marching Tune’ to

Christabel Pankhurst, Emmeline’s eldest daughter; the latter contains

several transposed fragments from Smyth’s earlier Women’s Social and Political Union anthem, ‘March of the Women’,

and I feel that this song requires more fervour and energy than we have

here. However, there’s a harmonic, phrasal and textural unpredictability

about ‘Possession’ which the duo exploit to convey the unsettling tension

in the text; and, voice and piano pull against each other, or simply

meander in their own fashion, in ways which suggest an innate uncertainty.

Smyth wrote of the mesmerising quality of Emmeline Pankhurst’s voice, in Female Pipings in Eden (1933), recalling: ‘a voice the deep

pitying inflexion of which I shall be able to make ring in the ears of

memory till my dying day. […] ‘a voice that, like a stringed instrument in

the hand of a great artist, put us in possession of every movement of her

spirit - also of the great underlying passion from which sprang all the

scorn, all the wrath, all the tenderness in the world.’ Such imagery

resonates during this performance. However, the strange opening song, ‘The

Clown’, which also develops the theme of ‘freedom’, has an acerbic

Weimar-ish quality, which Stevens and Marcus don’t quite tap with

sufficient piquancy or satirical sharpness.

De la Martinez - whose direction of

Retrospect Opera’s recent release of Smyth’s Fête Galante

I admired - conducts the Berkeley Ensemble in the Four Songs for voice and chamber orchestra which opens this disc,

and the enlarged timbral canvas significantly enhances the emotional range

and impact of these songs: there is a vivacity, diversity and mercurialness

which is beguiling. ‘Chrysilla’, in particular, highlights the sensitivity

and nuance of Stevens’ tone and phrasing.

The words of Sir Thomas Beecham seem apposite: ‘She was a stubborn,

indomitable, unconquerable, creature. Nothing could tame her, nothing could

daunt her, and to her last day she preserved these remarkable qualities.

And when I think of her, I think of her as a grand person, a great

character.’ Stevens and Marcus certainly reveal this ‘character’,

untameable and indomitable perhaps, but also intriguing and

thought-provoking.

Claire Seymour

[1]

Cornelia Bartsch, ‘Cyclic Organisation, Narrative and

Self-Construction in Ethel Smyth’s Lieder und Balladen,

Op.3 and Lieder, Op.4’, in edd. Aisling Kenny and Susan

Wollenberg, Women and the Nineteenth-Century Lied

(Ashgate, 2015), pp.177-216.