Mozart was moved to compose one in the Benda style but abandoned it.

Schumann got rid of the orchestra altogether and reduced the melodrama to a

single instrument - the piano. What Weber, Benda and Beethoven did with

melodrama was focus and magnify in a shortish scene on someone’s horror,

terror, or psychological disintegration.

Richard Strauss changed all that and, it is almost universally

acknowledged, not for the better. Enoch Arden certainly doesn’t

lack a first-rate text - it is after all written by Tennyson. Its narrative

is not without drama or emotional impact, either. Arden, a sailor, leaves

his family to go on a voyage in order to financially support them (though,

depending on how you read Tennyson’s poem this can be interpreted in

another way). He is shipwrecked on a desert island with two companions who

later die; Arden is left alone, lost and marooned for ten years. After he

is rescued, he arrives back to find his wife has remarried Arden’s best

friend, Philip, and has given birth to another child after long believing

Arden to have perished. Rather than ruin her happiness he never reveals he

is alive and dies of a broken heart. There is so much tragedy here Strauss

should have been able to have made something remarkable from it. He didn’t.

Tennyson’s literary influences - almost inserted into his poem like

leitmotifs, of which the piano part has many - are some of the most vivid

examples of creative genius. Homer’s Odyssey, Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, the Biblical Enoch, and, to a lesser extent,

Dumas’s The Count of Monte Cristo. If his Arden is not a

particularly mythological character, he is certainly one with masculine

identities. This is an Arden who is daring, adventurous and ambiguously

selfless. It is a contrast which Strauss could have used to some effect as

a dramatic foil against the dependable Philip Ray, or the wife, Annie, who

can barely find a husband outside a narrow triangle.

So, what went so wrong for Strauss in Enoch Arden? Length is

certainly an issue (performances can run just short of an hour). There is

also no Hoffmansthal to help Strauss out; rather, we have a translation of

Tennyson’s verses by Albert Strodtmann, one of the twelve translators of

this poem since the poem’s publication in Germany in 1867. Strauss may well

have been directly influenced by the 1895 Arden opera by Viktor Hansmann

or, more likely, Strodtmann’s third edition translation with Thumann’s

illustrations (a picture is so often worth more than a thousand words).

Another problem for Strauss might have had less to do with the masculinity

of Arden himself and more to do with the characterisation of Annie and how

she is developed in Tennyson’s poem.

Enoch Arden

was composed in 1897 - a time when Strauss was writing his great Tone Poems

like Don Juan, Macbeth, and Tod und Verklärung

and yet what you get in the melodrama is some of Strauss’s soggiest and

most sentimental music. Strauss would compose Ein Heldenleben just

a year later, in 1898, a work with its strong feminist line in the violin

solos which depict his wife, Pauline. Within a decade, Strauss would have

pushed the melodramatic feminine psyche to the absolute limit and beyond in

his two ground-breaking operas, Salome and Elektra. But Enoch Arden had none of this revolutionary zealousness and perhaps

it simply suffocated Strauss’s creativity because of it. Viewed in Germany

as “spineless”, a woman’s poem, it was perceived as a matrimonial tragedy

which appealed only to the prurience of women. A view became cemented that

this was a poem which celebrated bigamy and a certain kind of immorality.

This would almost certainly have seemed old-fashioned to the younger

Strauss who was standing at the door waiting to write some of the most

radical operas to open any new century.

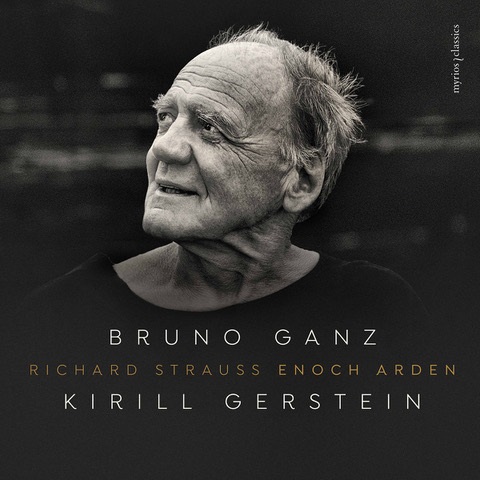

If the music and its structure fails what you have left are the performers

and this is where Enoch Arden has been somewhat lucky. As in any

melodrama it is the voice which is going to carry the poem and dating back

to the first recording in 1962 with Claude Rains and Glenn Gould some quite

remarkable narrators have made a recording. Almost without exception the

greatest recordings of Enoch Arden have been made by actors rather

than singers - Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, whose recording followed that of

Rains, Jon Vickers in 1998 (and his debut role as a speaker) and Benjamin

Luxon in 2007 lack the one thing that this part needs: the ability to

dramatize. You really wouldn’t want any of these singers to read a book to

you at bedtime - especially Vickers. Much more interesting are the

recordings by Rains, Gert Westphal, Michael York, Patrick Stewart and this

brand new recording by the late Swiss actor Bruno Ganz.

I’m not sure one would ever have thought of Claude Rains as a particularly

masculine actor, though the mystery he brings to his reading of Arden has

everything to do with an actor who could so clearly have worked wonders in

James Whale’s 1933 film The Invisible Man. Bruno Ganz, on the

other hand, is an entirely different kind of actor. His Arden is a study in

1930s expressionism, but it is also borne out of Goethe’s Faust. This is

probably the deepest, most tragically drawn portrait of Enoch Arden on

disc, and I am not sure you have to be fluent in German to sense that.

But you also feel that Ganz is extremely comfortable here - it recalls his

beautifully rendered work on Abbado’s 1993 recording of Nono’s Il canto sospeso with the Berlin Philharmonic. So much of this

work is sectionalised by Strauss, that it can almost feel like trunks of

text stitched rather badly to chords of piano writing and not much that

joins them together. Vickers rather surprisingly finds himself out on a

limb here, almost as if he has to be prompted by his pianist, the excellent

Marc-André Hamelin (though this perhaps is a singer’s typical response).

Rains and Ganz, on the other hand, aren’t phased by these elliptical

dropouts so both their pianists seem to follow them rather than the other

way around.

Kirill Gerstein, like Glenn Gould before him, doesn’t do understatement and

Strauss doesn’t really give this long work any kind of architectural frame

to hold it up; rather, it relies on its pianist to improvise a little to

disguise the work’s technical problems. Both Gould and Gerstein bring

enough style and brilliance to their playing to make any shortcomings the

work may have seem minor, though it would also be true to say with almost

any other actor/narrator than the one each is paired with on their

respective recording the dynamic of the performance would completely

change. This is foremost a work which is about the narrator.

There are now some twenty or so recordings of Strauss’s Enoch Arden, most of which were recorded after the 1990s when the

work really did seem to go through some kind of revival. There are versions

in several languages, including English, German and Italian. No English

language version comes close to the first, the 1962 recording with Claude

Rains and Glenn Gould (Columbia, nla). This most recent version by Bruno

Ganz and Kirill Gerstein is a clear first choice for a German language

recording of Tennyson’s poem but edges out the Rains/Gould for at least two

reasons.

Firstly, Ganz brings a kind of Herzhog-like depth to his narration which

goes well beyond the narrative itself. This is a reading which is as simple

as the words Ganz is speaking; but it is also an inspired allegory, a map

through theological symbolism, a deep rendering of one man’s elegy and

tragedy. This recording turned out to be Bruno Ganz’s final work but in

that one could now read different interpretations of this performance. For

Kirill Gerstein, his playing lacks none of the intensity that Glenn Gould

brought to his recording almost sixty years ago; what differs, is that

Ganz’s darker German reading of the text allows Gerstein to follow his

narrator into those rather gloomier corridors largely eschewed by others.

Strauss’s Enoch Arden was, in my view, one of those Strauss works

that was shipwrecked over a century ago and has yet to be properly rescued.

This Ganz/Gerstein recording is the closest - and might be the closest - we

get to rescuing this long-marooned work. Just not yet, though. Just not

yet.