Whether singing to the birds of the Warwickshire countryside from his rural

garden, participating in Wigmore Hall’s ground-breaking

live lunchtime recital series, or

popping up as Papageno - reliving memories of his 2017 Covent Garden performances by

self-accompanying ‘Ein Mädchen oder Weibchen’ with a percussion orchestra

of ‘tuned’ glasses and forks - Williams doesn’t seem to have had a ‘quiet’

lockdown in any sense of the word.

Another thing that seems to have been ringing regularly in my ears of late

is music from what is often termed the ‘English Musical Renaissance’, those

late Victorian and Edwardian years when English composers sought, by

drawing on folksong and music from the Tudor and Stuart period, to

establish a contemporary national musical idiom, distinct from but equal to

European traditions and styles. Williams has been a strong presence in this

regard too: alongside performances of Butterworth and Vaughan Williams,

Williams’ and pianist Susie Allan’s interpretations of

Sir Arthur Sullivan’s song-cycles

A Shropshire Lad

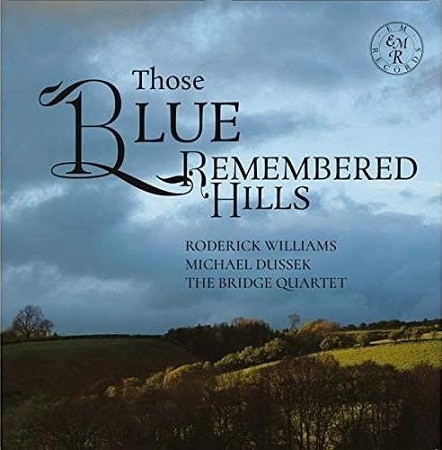

and Maud was released by Somm Recordings in May, and now we have

the opportunity to hear Williams return to Housman as set by Ivor Gurney,

alongside the music of Herbert Howells, on this splendid Em Records

release, Those Blue Remembered Hills.

The works presented on Those Blue Remembered Hills were all

composed between 1914 and 1925, and several are world premiere recordings.

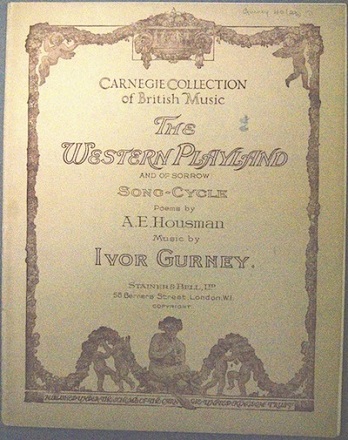

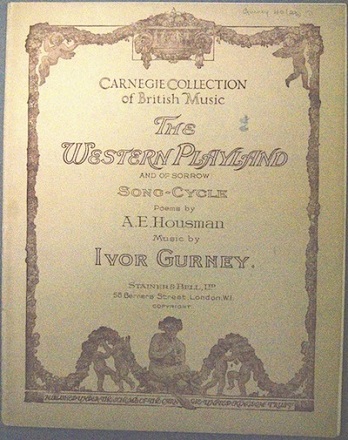

This disc opens with Gurney’s The Western Playland (and of Sorrow), a song-cycle comprising eight settings of poems from Housman’s A Shropshire Lad, in which Williams is joined by pianist

Michael Dussek and the Bridge String Quartet. These instrumentalists also

performed, with tenor Charles Daniels, on an earlier Em Records disc,

Heracleitus, which offered another Gurney setting of Housman, Ludlow and Teme,

composed in the same year. At the Royal College of Music, Gurney had

studied both German lieder and French mélodie traditions, but both of these

Housman song-cycles are evidently influenced by Vaughan Williams’ On Wenlock Edge (1909) which Gurney heard in 1919. They were

published as part of the Carnegie Collection of British Music, Ludlow and Teme in 1923 and The Western Playland in 1926.

Gurney had revised both scores while he was a patient at the City of London

Mental Hospital in Dartford, Kent, where he remained until his death in

1937 at the age of 47. The cycle is presented here in a new edition by

Philip Lancaster, who explains (in one of several of the liner book’s

illuminating articles, and

elsewhere) that Gurney’s revisions were quite substantial - ‘textures were added and

reworked, the scoring often wholly altered (one song originally scored

largely for strings was in revision accompanied largely by piano);

harmonies became more diffuse, in Gurney’s impressionistic vein; and the

songs in parts substantially redrafted’ - and sometimes very problematic

(in one case, leading Lancaster to return largely to the original 1920

version). Reflecting on the title, Lancaster speculates that title of The Western Playland alludes to both the Western Front and to

Gurney’s home county of Gloucestershire, while ‘and of Sorrow’ which was

added in 1925 may be inspired by A Shropshire Lad poem, not set

here:

‘In my own shire, if I was sad,

Homely comforters I had:

The earth, because my heart mas sore,

Sorrowed for the son she bore;

And standing hills, long to remain,

Shared their short-lived comrade’s pain.’ (XLI)

As one would expect, Gurney’s musical responses to Housman’s poems are

sensitive and intensely lyrical. Listening to the cycle for the first time,

I heard a Brahmsian touch in the melodies, but I was struck by the

flexibility of Gurney’s forms and melodies as he shapes each song and

phrase precisely to the sounds and sense of the poetic text, and by the

surprisingly unpredictable harmonic twists and heightenings. The

instrumental accompaniments are no less diverse in timbres, texture and

colour, and they serve as sonic landscapes which support the verbal meaning

and emotion. The songs present considerable technical challenges for all

the performers. The instrumentalists must balance ever-changing textures,

while the singer must negotiate sometimes angular melodies which rove

through restless rhythmic shapes and wide-ranging tessituras. The smooth

legato that Williams sustains, seemingly effortlessly and always

articulating the texts with precision and finely judged emphasis, is

notable.

Roderick Williams

Roderick Williams

‘Reveille’ is a stirring dawn cry, the first three stanzas opening with

exhortations to “Wake”, “Wake”, “Up, lad, up, ’tis late for lying”: time

passes, each moment must be lived to the fullest. But, ‘reveille’ does not

just infer sunrise, it is also the word used to describe the bugle-call

that wakes the military, and we hear the beat of soldiers’ drums in the

firm stamp of the piano bass and cello. Williams brilliantly unites lyrical

vocalism with declamatory briskness, and echoes between instruments and the

voice conjure energy. Though the central section is more dreamy, with

thoughts of lands untrod and beckoning hovering softly in the upper

strings, up and onwards it must be. Yet, the quietude of the postlude and

the poignancy of the viola’s ‘last word’ remind us, “There’s be time enough

to sleep” - as Gurney himself confirmed in his own eloquent song to that

‘eternal rest’.

The theme of transience is developed in ‘Loveliest of Trees’ in which the

seventh-based harmony of the opening and impressionistic progressions

create a fleeting, vulnerable quality. There is such delicate melancholy in

the falling motif - a blossom floating gently to the ground - which opens

the piano introduction and vocal line, and which the strings, generally

restrained throughout, develop in the eloquent postlude. This is the sort

of song, and singing, which warms the heart even as it brings hot tears to

one’s eyes. Indeed, “With rue my heart is laden” sings the poet-speaker

after the strings’ tender introduction to the more folk-like ‘Golden

Friends’. Williams’ often unaccompanied vocal line is wonderfully light and

even, threatening at times, it seems, to disappear but softly sustaining

its recollections of “lightfoot boys” and “rose-lipt girls … sleeping in

fields where roses fade”, until a whispered postlude unfurls sweetly into

silence.

Gurney was a keen sportsman as a schoolboy, and football and cricket

momentarily keep grief at bay, sustaining a lust for life in the brief

‘Twice a Week’. Williams’ baritone may be strong and resolute but the

singer’s sentiments are belied by the brusqueness of the gruff, dissonant

strings and the rhythmic instability of the song (which Williams negotiates

with pinpoint accuracy), especially in the final stanza where the

thundering syncopation in the piano bass, mis-accented text-setting and

dense string discords seem to disdainfully sneer. ‘The Aspens’ is folk-like

rumination on eternal nature’s indifference to man’s transience, seen

through the eyes of a widower who predeceases his second wife, thereby

perpetuating the cycle of love and loss. Williams’ unaccompanied vocal

entries are sweet and sure, and the long phrases - the time-signature

ceaselessly changing - extend with lyrical eloquence, accompanied

alternately by strings and piano, the instruments coming together when the

voice is silent. Each time the singer notes the watching aspen, the vocal

line rises to a peak and then falls an octave interval, and the smooth

evenness with which Williams’ shapes this expressive gesture is deeply

moving.

Michael Dussek.

Michael Dussek.

Gurney eschews the invitation in ‘Is my team ploughing’ to vocally

distinguish the ballad’s speakers preferring instead to oppose the text and

accompaniment to underline the song’s poignancy. For example, the questions

from the man who lies in the earth, “Is my team ploughing”, “Is football

playing … Now that I stand up no more?” are answered by the relentless

jigging, jangling quavers in the piano and strings which cruelly tease with

their undeniable presence and vigour. Tension builds as the harmonies and

textures complicate, but “Is my girl happy” interrupts: a pianissimo

dynamic, a descending vocal phrase and the commencement of an ominous

syncopated low octave pedal in cello and piano bass lead to a solo parlando question, sung with quiet but heart-wrenching directness

by Williams, “And has she tired of weeping/ As she lies down at eve?” The

strings’ hushed answer ‘replies’ powerfully and plaintively. This is a

tremendous unity of lyricism and drama.

However, The Western Playground ends in more joyful fashion, with

‘March’, a setting of the longest poem of the eight, ‘The sun at noon to

higher air’. The piano’s light arpeggio triplets, symmetrically patterned,

and the strings’ concordant sweetness conjure youthfulness and optimism,

while the constant lilt of two-against-three creates a naturalism and

freedom that is perfectly embodied by the relaxed warmth of Williams’ baritone.

There are pauses for instrumental reflection between the stanzas, and a

more ambiguous mood marks the fourth stanza’s mirage-like, symbolist vision

of farm girls resting in the palms’ shadows beside the pond’s and hedge’s

“waving silver-tufted” wands. But, with the firm assertion that “lovers

should be loved again”, Gurney closes not with loss and longing but with

life and love. The lingering postlude at first seems to question such

certainty, but eventually the piano’s dark reverberations, the high silvery

violins and the aspiring ascents of cello and viola dissolve into stillness

and peace.

If I have spent a long time describing The Western Playground it

is because Gurney’s cycle, and even more so this brilliant performance by

Williams, Dussek and the Bridge Quartet, make this disc an absolute

must-have, not just for Gurney aficionados but for all lovers of English

song, indeed all song. But, Those Blue Remembered Hills

offers much more too.

There are four songs by Herbert Howells, including ‘There was a Maiden’ and

‘Girl’s Song’ from Fours Songs Op.22 (1916). In the first,

Williams seems to inject a tint of wisdom into his baritonal warmth - a

note of maturity to balance the shimmering melancholy of the piano’s

oscillating patterns. Here, the baritone’s verbal pointings add much to the

simple strophic form: “The cold wind blows across the lea”,

sending a shiver through one’s spine, while the description of the maiden,

“pale, so pale, with never a rose”, makes one fear for the

vulnerable lass. ‘Girl’s Song’, brimming with desire and visceral feeling,

may last less than 90 seconds, but Williams and Dussek offer a masterclass

in musical articulation and expression. Howell’s setting of a text by

Northumbrian poet Wilfrid Gibson, ‘The Mugger’s Song’, is an unpretentious,

boisterous rural character-study, precisely drawn here; best of all is the

compelling directness and simplicity of ‘King David’, with its ‘antique’

modal and pentatonic tints. Both Williams and Dussek rise to tremendous

heights of eloquent expression.

The Bridge Quartet

The Bridge Quartet

There are further songs by Gurney too, the ballad ‘Edward, Edward’ - a

setting from the Reliques of Thomas Percy, in which Williams’ has

a good stab at Scots brogue - and one of Gurney’s best-known songs, ‘By a

Bierside’ (a song which was orchestrated by Howells), which Gurney’s Collected Letters (ed. R.K.R. Thornton) reveal ‘came to birth in a

disused Trench Mortar emplacement’ and which brings the disc to a close.

Williams’ demonstrates that his wistful head voice, bold middle range, and

probing deep bass-like resonance are equally affecting. I could literally

feel the thunderous shine of Williams’ proclamation of John Masefield’s

final words, “It is most grand to die”, pulse in my heart, before the

tranquil repetition “so grand” quietened the passion. Heracleitus

had included an Adagio for string quar1tet played by the Bridge

Quartet, which is an earlier version of the D Minor String Quartet heard in

full on this disc - a world premiere recording.

Why is it that these English poets and composers - Georgians and Edwardians -

seem to speak so strongly to us still? I don’t think that it is simply that

they console, or feed, a nostalgia for an Edwardian twilight, more that

there are times, in any age and place, when we long for what we imagine was

a simpler age.

In a letter to his friend Marion Scott (musicologist, poet,

composer, violinist and more) dated December 1916, Gurney reflected on life

in the trenches in France: ‘After all, my friend, it is better to live a

grey life in mud and danger, so long as one uses it - as I trust I am now

doing - as a means to an end. Someday all this experience may be

crystallized and glorified in me; and men shall learn by chance fragments in

a string quartett [sic] or symphony, what thoughts haunted the minds of men

who watched the darkness grimly in desolate places.’ This recording confirms that Gurney did indeed crystallise and glorify those experiences in words and music.

Before listening to this disc, I could not imagine anyone who could better capture the poignancy of that

suffering, and the beauty which rises from it, and transcends it, than Roderick

Williams. Having listened to Those Blue Remembered Hills, I do not

think that Williams has done anything finer.

Claire Seymour