Somervell, who studied with Stanford and King’s College, Cambridge, and

was, during his subsequent RCM studies, a private pupil of Parry, was in

his day a composer of some repute but is now more renowned as a music

educator. He served as Inspector of Music on the Board of Education from

1901-28.

His commitment to English song indicates both a strong feeling for these

Victorian poets, all of whom (again excepting Housman) had died when

Somervell set their poetry, and also a belief in what he described as

‘power of national song in the formation of character’: ‘I believe three

generations of Englishmen, familiar from childhood with Irish song and

story, and three generations of Irish, equally familiar with English song

and story, would produce two nations who would understand one another and

would be able to agree how to live, either together or apart.’ Such views

were embodied by The National Song Book which Stanford published

in 1906 with Somervell’s support. Moreover, elsewhere Somervell, in accord

with the views of the contemporary ‘English musical renaissance’, wrote of

‘the suppression of national musical expression’ and ‘the blight of the

foreign exploiting musician’.

Trevor Hold, in English song Parry to Finzi: Twenty English Song-composers, describes

Somervell’s Maud (1898) as ‘the first successful English

song-cycle … one of the masterpieces of English song’. It was perhaps a

surprising choice of text as Tennyson’s poem, published in 1855 at the

height of the Crimean War, had been and still was at the end of the century

one of the Poet Laureate’s least popular works. Its unstable narrative

voice and perspective were criticised as obscure; the religious doubt

expressed was suspect; and, in an article in Quarterly Review,

William Gladstone condemned its apparent glorification of the war in

Crimea. To make the narrative clearer, Tennyson added extra lines to later

editions; interestingly, Somervell too found it necessary to add a thirteen

song to his original twelve for the same reason, adding Song 6, ‘Maud has a

garden’, in 1907.

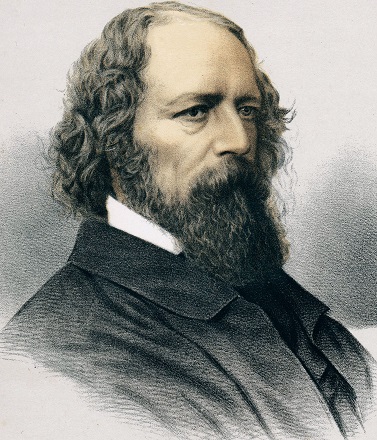

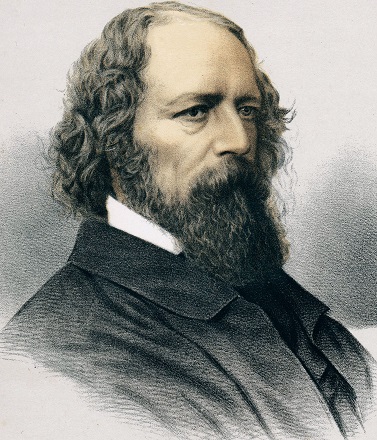

Lord Alfred Tennyson. Lithograph. The Modern Portrait Gallery (1890). © Jupiter Images.

Lord Alfred Tennyson. Lithograph. The Modern Portrait Gallery (1890). © Jupiter Images.

But, in many ways, the mental anguish of Tennyson’s unstable, possible

insane, poet-speaker, who has loved and lost and who seems to long for a

visionary reunion with the dead, is ideal song-cycle material. The poem

unfolds in the present tense and thus has intimacy and immediacy. The

narrator’s strange, ambiguous ravings create emotional and dramatic

intensity. Tennyson’s stanza- forms are diverse and ever-changing, like the

restless flux of the narrator’s mind, and this furnishes a composer with

rich range of potential musical forms.

Somervell’s published score contained a prefatory note which summarised

Tennyson’s poem and explained the place of each song within the narrative,

thereby enabling him to excise sections which furthered the ‘plot’. He set

only 234 of Tennyson’s 1324 lines (verbatim, with just two very minor

alterations), omitting fifteen poems and reducing all but two of those he

retained.

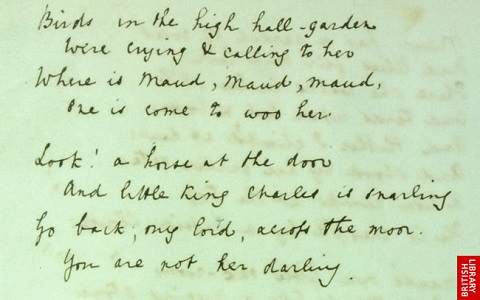

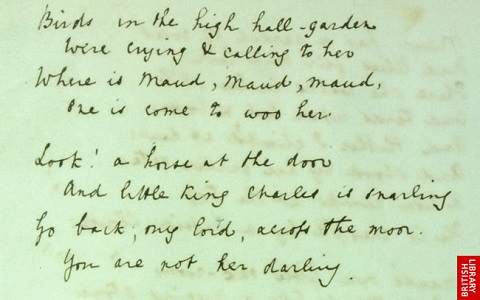

Tennyson’s fair copy of Maud © British Library.

Tennyson’s fair copy of Maud © British Library.

The poet-speaker is tormented by the death of his father, which took place

in ‘the dreadful hollow’ (suicide is implied but never confirmed). He falls

in love with his father’s rich friend’s daughter, Maud (to whom, in the

poem he has a hazy memory of having been betrothed), and although her

brother disapproves, he wins her love. He visits her garden, his mind

darkened by the curtained house which makes him think of death. Though he

is not invited to the dance which is taking place inside, he is ecstatic at

the thought of her arrival at their appointed meeting. He hears her coming

but her brother follows her; a duel ensues during which the brother is

killed, again in the ‘dreadful hollow’. He flees, sinks into insanity, and

in his absence Maud dies. He longs to hold her in his arms and sees a

vision of her in his dreams, where she speaks of her ‘hope for the world in

the coming wars’. He accepts his duty of service and ‘embraces the purpose

of God, and the doom assigned’.

In this new Somm label recording, baritone Roderick Williams suggests that,

in contrast to Tennyson’s contemporary readers, nowadays we might be more

inclined to view the traumatised protagonist as “a victim of circumstances

rather than a malevolent perpetrator” but admits that he still found

himself “uncomfortable with Somervell’s beautiful music initially as I

couldn’t square it with the disturbed state of mind of the speaker”. These

are not “‘conventional’ love songs”, he observes.

Indeed, although they are conventional, or at least conservative,

in other ways: in terms of the musical style of many of the songs, the

Victorian parlour song comes to mind. That they assume a far greater,

richer and stature in this recording is in no small part to the astuteness

of Williams and his frequent musical partner, Susie Allan, in intimating

the musical and poetic undercurrents.

Roderick Williams. Photo courtesy of Groves Artists.

Roderick Williams. Photo courtesy of Groves Artists.

Somervell does not miss a rhetorical trick in the opening song. Gothic

cascades sweep up and down the piano keyboard as the narrow arioso saves

its flourishes for the “silent horror of blood” and the Echo’s answer,

“Death”. Williams and Allan do well to keep the melodrama of this short

prelude in check, but the mood changes markedly when the poet-speaker

introduces us to Maud, as “A voice by the cedar tree”, singing of “men that

in battle array”, of “Death, and Honour that cannot die”. Williams

perfectly conveys the instability of the speaker’s psyche. With gentle

evenness he captures his joy and delight in her sweetness; Maud’s martial

song inspires dynamic and strength of colour; a dark, diminishing descent

from a high head voice evokes his vision of despair, “myself so languid and

base”, before Allan pushes forward once more, pulling him from his

self-destructive inertia.

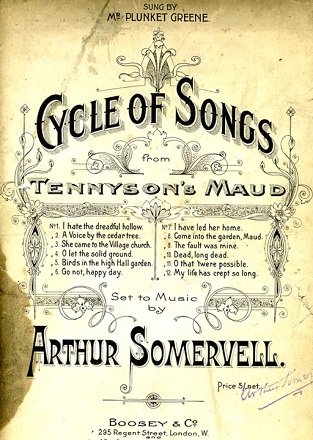

Titlepage of Somervell’s Maud, Boosey & Co. (1898).

Titlepage of Somervell’s Maud, Boosey & Co. (1898).

Without mannerism, in ‘She Came to the Village Church’ Williams uses

thoughtful diction and carefully placed vocal nuances to make us feel us

the intensity of the poet-speaker’s psychological tussles. If long piano

postludes sometimes restore calm, then a sort of wild optimism begins to

accrue: “What matter if I go mad,/ I shall have had my day.” (‘O let the

solid ground’) he boldly, defiantly declares. This hope propels him into

Maud’s garden: the frolicking piano paints a picture of the twilight birds

and woodland lilies, and of his light heart as his woos her with a kiss

placed upon her slender hand. This uplift ripples through ‘Maud has a

Garden’, but as the vocal urgency grows, so it tips towards dismay: the

sight of the “death-white curtain drawn” tugs the poet-speaker into

disillusion, the piano’s reversing, tumbling minor-key arpeggio landing

with an ominous shudder, “the sleep of death”.

There’s a slight desperation beneath the trotting blitheness of ‘Go Not,

Happy Day’, with its red images of roses, blushes and cedar-trees. Then, in

‘I have led her home’ the self-assuring repetition of superlatives - “There

is none like her, none”, “never yet so warmly ran my blood/ And sweetly” -

suggests an infatuation, the danger of which is wonderfully intimated by

the interrupted cadence which shatters the song’s - perhaps the poem’s -

highpoint of tranquillity, as the poet-speaker feels “close on the promised

good”. ‘Come into the garden, Maud’ is the peak of his hopes, a twirling

waltz that lifts his spirits high. With tremulous elation, Williams exults,

“She is coming, my life, my fate”, but the poem’s final image of the

poet-speaker’s century-old “dust” trembling beneath Maud’s feet, “And

blossom in purple and red”, is a portentous one and the piano’s surging

apotheosis is one of delusion, not fulfilment.

Photo credit: ‘The Soul of the Rose’, John William Waterhouse (1903)

Photo credit: ‘The Soul of the Rose’, John William Waterhouse (1903)

The changes that Somervell makes in his adaptation of Tennyson’s poem are

small in nature but significant in effect. Most marked is his reversal of

the order of songs 11 and 12 with respect to their position within the

poetic text. The poet-speaker’s dream of resurrected love, ‘O that ’twere

possible’ (Somervell’s song 12), follows not his expression of guilt for

the death of the brother, ‘The fault was mine’ (10), but the grief and

despair of Maud’s loss, ‘Dead, long dead’ (11). The dreadful listlessness

of ‘The fault’, evoked by the piano’s tolling ostinato and Hadean steps, is

deepened by occasional flourishes recalling the horror of the first song.

Here, the clarity of Williams’ diction reveals the perceptive power of his

musical and poetic insight, as the poet-speaker looks in self-loathing at

“this guilty hand!” and laments Maud’s “cry for a brother’s blood” that

will “ring in my heart and ears, ’till I die, ’till I die.” Is it too

fanciful to hear the piano’s major-key closing cadence as a glance ahead at

the submission into death in the final song? There seems to me, too,

something reminiscent of Britten’s word-setting in this tremendous song.

Indeed, Williams conjures an almost Grimes-like mania in ‘Dead, long dead’,

the turbulent clamour of the imagined horses’ hooves beating into his scalp

and brain as his bones “shaken with pain” are thrust “into a shallow grave”

culminating in a literal shout of fury, a vocal fist of frustration and

despair: “to hear a dead man chatter/ Is enough to drive one mad.” Why have

they not buried me deeper, he anguishes; surely some “kind heart will come/

To bury me, bury me/ Deeper, ever so little deeper”. Williams’ whispers the

final word, its syllables broken pronouncedly, like two last breaths, with

heart-breaking sombreness.

No wonder the brief snatch at a dream, “O that ’twere possible … To find

the arms of my true love/ Round me once again!”, cannot banish the deathly

defeatism and derangement of the preceding two, much longer songs. The

futility is made more poignant still by the beauty and earnestness of the

vocal line and tender piano support. The sparseness of the cycle’s longest

song, ‘My life has crept so long’, and the repetitions of a ponderous

descending melody in both voice and piano confirm that hope and reason have

drained away. All that is left is loss. Memories of the “one thing bright”

do stir a resurgence, but it is a false dawn. The dream has vanished and

only a brutal reality remains: “We have proved we have hearts in a cause,

we are noble still./ I have felt with my native land. I am one with my

kind”, sings the poet-speaker with bold and unflinching acceptance of his

duty - one that will enable him to embrace “the doom assign’d” and be

again, in death, with Maud.

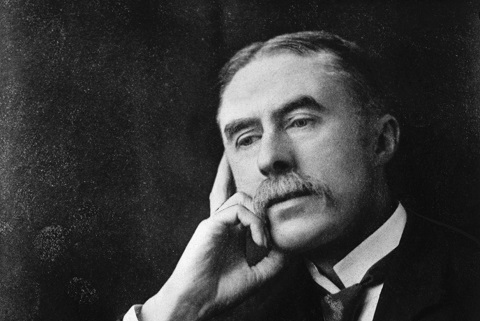

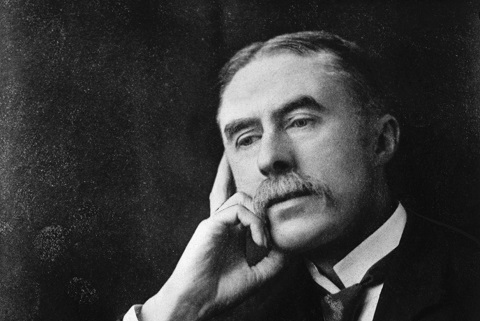

A.E. Housman. Photo credit: Hulton-Deutsch/Hulton-Deutsch Collection.

A.E. Housman. Photo credit: Hulton-Deutsch/Hulton-Deutsch Collection.

Somervell’s A Shropshire Lad (1904) is, as Hold points out, the

first Housman song-cycle and may even be the first Housman setting,

composed as it was just eight years after the poem’s publication (Stephen

Adams, the alias used by Michael Maybrick, published a single song, ‘When I

was one-and-twenty’, in the same year). It follows much the same narrative

and psychological trajectory as Maud. Although Housman presents no

coherent narrative, Somervell’s selection and arrangement of the poems

takes us from the protagonist’s youthful reflections on nature, life and

love, through the sadness of fractured love, to loneliness and desolation,

and finally to his departure, as a soldier, to do his duty. Housman does

not offer the composer the sort of elaborate imagery to which Somervell

responds so evocatively in Maud, and I feel that in this cycle,

which is certainly lyrical and melodious, the composer was not so alert to

the ironic undercurrents of Housman’s text. Instead he prefers a more

literal representation of its images and sounds, from the buoyant soldiers’

march of ‘The street sounds to the soldiers’ tread’, in which a realistic

diminuendo and sparseness depict the redcoats as they recede into the

distance in piano postlude, to the single-note beating which we hear in ‘On

the idle hill of summer’, “the steady drummer/ Drumming like a noise in

dreams”.

There are more strophic settings, such as the opening song, ‘Loveliest of

trees’, in which the mellifluousness of Williams’ baritone and the

melodiousness of the song seem a perfect match: the very simplicity of the

setting and the singing here are its merit. ‘When I was one-and-twenty’ has

a cheery breeziness but it’s a pity that Williams, unlike Allan who clips

the rhythms very tightly, is a bit lazy with the dotted rhythm in the first

line of each stanza, since this gesture captures the irony of an older

poet-speaker’s wry glance back at his cocksure younger self.

Susie Allan. Photo credit: Bill Wyatt.

Susie Allan. Photo credit: Bill Wyatt.

There are many adroit switches of mood: from dark melancholy of ‘There pass

the carless people’ to the carefree charm of ‘In summertime on

Bredon’: in the latter, Williams’ lovely relaxed head voice is tempered

with the poet-speaker’s remembrance of loss, before reassurance returns.

Similarly, the duo switch between martial tautness and hymn-like solemnity

in ‘On the idle hill of summer’, before an appropriately grandiose

conclusion. Both performers are agile in ‘Think no more, lad, laugh, be

jolly’, where nuances of harmony, the wide vocal range and subtleties of

tempo do inject irony. In contrast, stillness is the core of ‘Into my heart

an air that kills’: Somervell sets the first part of the poem on a monotone

Bb, and the sustained evenness is wonderful, all the more so because

Williams and Allan resist the temptation to turn up the temperature in the

second part of the song when the melody expands. But, why does Williams

move (I think?) from this Bb for a single note at the end of the second

poetic line, “From you far count-ry blows”, to an A natural to

accord with the piano harmony, when surely the point of the

dissonance is to highlight the speaker’s introspective abstraction from

reality as he reflects upon “the land of lost content” which he sees

“shining plain”?

But, it really feels as if, in noting such minor details, I’m trying to

find something to criticise! There is a lovely ease in ‘The Lads in their

hundreds’: we hear in this song Williams the master story-teller. Best of

all is ‘White in the moon the long road lies’. I feel that the musical

rhetoric is more sophisticated here but, in fact, the sheer beauty of

Williams’ singing is what really beguiles: the duo show how telling a pianissimo and silence can be, and the poignancy of the ironically

consoling postlude which follows the singer’s concluding lines, “White in

the moon the long road lies/ That leads me from my love”, is deeply

touching.

Each of the two cycles is followed by a single song: ‘The Kingdom by the

Sea’, a setting of Edgar Allan Poe, follows Maud, while the disc

concludes with a setting of the ‘Shepherd’s Cradle Song’.

I’ve had this lovely recording playing on loop for days. And, it has sent

me back to my well-thumbed copies of Tennyson and Housman. I can’t praise

it highly enough.

Claire Seymour