18 Jul 2020

Carlisle Floyd's Prince of Players: a world premiere recording

“It’s forbidden, and where’s the art in that?”

The Sixteen continues its exploration of Henry Purcell’s Welcome Songs for Charles II. As with Robert King’s pioneering Purcell series begun over thirty years ago for Hyperion, Harry Christophers is recording two Welcome Songs per disc.

In February this year, Albanian soprano Ermonela Jaho made a highly lauded debut recital at Wigmore Hall - a concert which both celebrated Opera Rara’s 50th anniversary and honoured the career of the Italian soprano Rosina Storchio (1872-1945), the star of verismo who created the title roles in Leoncavallo’s La bohème and Zazà, Mascagni’s Lodoletta and Puccini’s Madama Butterfly.

Collapsology. Or, perhaps we should use the French word ‘Collapsologie’ because this is a transdisciplinary idea pretty much advocated by a series of French theorists - and apparently, mostly French theorists. It in essence focuses on the imminent collapse of modern society and all its layers - a series of escalating crises on a global scale: environmental, economic, geopolitical, governmental; the list is extensive.

Amongst an avalanche of new Mahler recordings appearing at the moment (Das Lied von der Erde seems to be the most favoured, with three) this 1991 Mahler Second from the 2nd Kassel MahlerFest is one of the more interesting releases.

If there is one myth, it seems believed by some people today, that probably needs shattering it is that post-war recordings or performances of Wagner operas were always of exceptional quality. This 1949 Hamburg Tristan und Isolde is one of those recordings - though quite who is to blame for its many problems takes quite some unearthing.

The voices of six women composers are celebrated by baritone Jeremy Huw Williams and soprano Yunah Lee on this characteristically ambitious and valuable release by Lontano Records Ltd (Lorelt).

As Paul Spicer, conductor of the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire Chamber Choir, observes, the worship of the Blessed Virgin Mary is as ‘old as Christianity itself’, and programmes devoted to settings of texts which venerate the Virgin Mary are commonplace.

Ethel Smyth’s last large-scale work, written in 1930 by the then 72-year-old composer who was increasingly afflicted and depressed by her worsening deafness, was The Prison – a ‘symphony’ for soprano and bass-baritone soloists, chorus and orchestra.

‘Hamilton Harty is Irish to the core, but he is not a musical nationalist.’

‘After silence, that which comes closest to expressing the inexpressible is music.’ Aldous Huxley’s words have inspired VOCES8’s new disc, After Silence, a ‘double album in four chapters’ which marks the ensemble’s 15th anniversary.

A song-cycle is a narrative, a journey, not necessarily literal or linear, but one which carries performer and listener through time and across an emotional terrain. Through complement and contrast, poetry and music crystallise diverse sentiments and somehow cohere variability into an aesthetic unity.

One of the nicest things about being lucky enough to enjoy opera, music and theatre, week in week out, in London’s fringe theatres, music conservatoires, and international concert halls and opera houses, is the opportunity to encounter striking performances by young talented musicians and then watch with pleasure as they fulfil those sparks of promise.

“It’s forbidden, and where’s the art in that?”

Dublin-born John F. Larchet (1884-1967) might well be described as the father of post-Independence Irish music, given the immense influenced that he had upon Irish musical life during the first half of the 20th century - as a composer, musician, administrator and teacher.

The English Civil War is raging. The daughter of a Puritan aristocrat has fallen in love with the son of a Royalist supporter of the House of Stuart. Will love triumph over political expediency and religious dogma?

Beethoven Symphony no 9 (the Choral Symphony) in D minor, Op. 125, and the Choral Fantasy in C minor, Op. 80 with soloist Kristian Bezuidenhout, Pablo Heras-Casado conducting the Freiburger Barockorchester, new from Harmonia Mundi.

A Louise Brooks look-a-like, in bobbed black wig and floor-sweeping leather trench-coat, cheeks purple-rouged and eyes shadowed in black, Barbara Hannigan issues taut gestures which elicit fire-cracker punch from the Mahler Chamber Orchestra.

‘Signor Piatti in a fantasia on themes from Beatrice di Tenda had also his triumph. Difficulties, declared to be insuperable, were vanquished by him with consummate skill and precision. He certainly is amazing, his tone magnificent, and his style excellent. His resources appear to be inexhaustible; and altogether for variety, it is the greatest specimen of violoncello playing that has been heard in this country.’

Baritone Roderick Williams seems to have been a pretty constant ‘companion’, on my laptop screen and through my stereo speakers, during the past few ‘lock-down’ months.

Melodramas can be a difficult genre for composers. Before Richard Strauss’s Enoch Arden the concept of the melodrama was its compact size – Weber’s Wolf’s Glen scene in Der Freischütz, Georg Benda’s Ariadne auf Naxos and Medea or even Leonore’s grave scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio.

“It’s forbidden, and where’s the art in that?”

On August 18th 1660, diarist Samuel Pepys recorded his thoughts about ‘one Kinaston [sic], a boy’ who ‘acted the Duke’s sister [in The Loyall Subject] but made the loveliest lady that ever I saw in my life’. Edward Kynaston was, Pepys later observed, ‘the prettiest woman in the whole house’.

Edward Kynaston (c.1640-1712) was one of the last ‘boy players’ of the Restoration theatre. As an actor who performed women’s roles, in a highly mannered style, he attained the pinnacle of theatrical success at the Duke’s Theatre, London. Kynaston’s star fell when, to please his mistress - sometime orange-seller and aspiring actress, Nell Gwynn - Charles II issued a royal decree in 1661, permitting women to perform on the theatrical stage: “No He shall ere again on an English stage play She.”

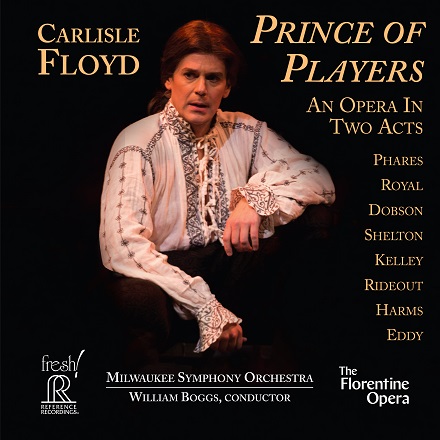

Kynaston is the eponymous protagonist of Carlisle Floyd’s opera Prince of Players, first staged at the Houston Grand Opera in March 2016. The Florentine Opera Company and Milwaukee Symphony have now released the world premiere recording, on the Reference Recordings label.

Since his first opera, Susannah, was staged by New York City Opera in 1956, Floyd has been seen by many as the ‘father of American opera’, and the success of his operas - lyrical in idiom, focused on American settings and contexts, principally from the 19th and 20 th centuries - has encouraged younger composers such as Jake Heggie and Mark Adamo to engage with the genre. Eleven successful operas later, Floyd professed to have laid his composer’s pen to rest following Cold Sassy Tree (2000), devoting himself to caring for his wife, who died in 2010. Prince of Players is therefore something of a late and unexpected bloom of creativity.

Floyd’s interest in Kynaston’s artistic and personal ‘crisis’ was prompted by Richard Eyre’s film Stage Beauty (2004), which was itself based upon Jeffrey Hatcher’s play, Compleat Female Stage Beauty (1999). The opera begins and ends with Shakespeare. In the Prologue to Act 1, in a theatre newly re-opened by the reinstituted monarch, Kynaston enacts, in stylised fashion, Desdemona’s death at the hands of Othello, the latter played by the Duke Theatre’s actor-manager, Thomas Betterton. In the final scene of Act 2, Kynaston is himself the jealous murderer, the role of the Moor’s innocent wife being taken by Kynaston’s former dresser, Margaret (‘Peg’) Hughes. Kynaston’s path from artifice to naturalism, from carefree success to a catastrophic fall, is charted by royal receptions, managerial bust-ups, unemployment, drag queen notoriety, a beating at the hands of thugs employed by the ridiculed fop Sir Charles Sedley, admissions of childhood abuse, sexual re-orientation, and declarations of love. It’s a steep ‘learning curve’.

The Prologue to Act 1 presents an ominous timpani pedal and astringent woodwind wriggles, evoking not just Shakespeare’s envious green-eyed monster but also the underlying disquiet which threatens Kynaston’s identity, professional security and personal happiness. Floyd’s idiom is perhaps less prevailingly lyrical than in his previous operas, with more declamatory and quasi-speech vocalisation. The diction of cast and chorus is uniformly excellent - and the Soundmirror engineers have done a terrific job. There are frequent and lengthy instrumental interpolations within and between scenes, and at times the pedal points get a little tiresome. There are also snatches of neo-Baroque counterpoint, song, dance and fanfare, not quite carried off with the invention and subtlety with which Britten revisited the Elizabethan past in Gloriana.

As the eponymous Prince of Players, Keith Phares sings with vibrancy and impact. In the final scene of Act 1, when Kynaston appeals to the King not to allow women to perform on the stage, he injects an urgent tension into his warm baritone. But, Floyd’s Sondheim-esque outpouring when the desperate actor pleads his case - “I was an orphan and a chimney sweep, put out on the streets before I was eight … I worked and I worked for four long years until at last I was on the stage where i still perform today. This is my life and the lives of others like me. I beg you, entreat you, not to take our lives away.” - is not entirely convincing. Ditto the Copland-esque folksiness which accompanies Kynaston’s declaration of love and loyalty, sealed with a kiss, when his lover, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, declines to take him as his guest to dine with King Charles. And, Nell Gwynn’s ‘spirited folk ballad filled with roulades’ seems similarly out of place as an ‘audition piece’ before the King, though Rena Harms sings with freshness and vitality, her tone bright and excitable, with a thrilling gloss that seems to point straight towards the theatre.

In Act 2, Phares adopts a new identity, as ‘Lusty Louise’ - “that cock- sure madam, that ballsy bawd, that Paragon of beauty and all things refined” - and fires off an impressive falsetto when impersonating the disappointed bride who laments, “No balls at all, no balls at all! I’ve married a man with no balls at all!”

We gain most insight into Kynaston’s dilemma in Act 1 Scene 3 when, on the stage of the Duke’s Theatre, stripped of makeup, gown and wig, he stands beside Desdemona’s bed in his underpants, and undergoes ‘an elaborate ritual of the hands which silently expresses a full range of emotions from the most exalted joy to the most wracking grief, all mirrored in his face at the same time’. The orientalism of the flute solo evokes both strangeness and beauty, the oboe and clarinet then add a certain wistfulness, while unrest ensues in the dissonant harmonic twists.

Chad Shelton bellows with fittingly pompous sonorousness as the self-righteous and self-absorbed monarch. Alexander Dobson (Thomas Betterton), Frank Kelley (Sir Charles Sedley) and Vale Rideout (Villiers, Duke of Buckingham) vocally capture their characters with perception and skill. The Florentine Opera Chorus are in assertive voice from their first vibrant cries, “Bring back the lady, bring back Desdemona!”

But, it’s Kate Royal, as Peg Hughes who outshines all. Initially earnest and sympathetic, when disparaging the “chattering ninnies with magpie minds” (Miss Frayne and Lady Meresvale, sung by Nicole Heinen and Briana Moynihan respectively) who usher Kynaston into the night following his theatrical triumph as Desdemona, Royal finds touching lyrical sincerity when singing of Peg’s dreams and her love: “One day, perhaps one day my love will find its voice!” Her declaration, “More than anything in all the world, I want to be a player. To perform the roles that you perform, and on this very stage”, shimmers with truthful feeling, all the more powerful because of the theatrical unreality in which it is embedded.

The opera’s musical highpoint comes following Kynaston’s beating by Sedley’s thugs. Here, Floyd’s sensitive writing for bass clarinet, flute and cor anglais is beautifully interpreted by the players of the Milwaukee Symphony, conducted by William Boggs - and Floyd finds a musical sincerity that is sometimes lacking.

In his liner book article, ‘Carlisle Floyd and American Opera’, J. Mark Barker suggests that ‘Though set in 17th-century England, the opera’s highly charged drama deals with issues that confront us in 21st-century America - among them, the intricacies of sexual orientation and gender identity, and the resulting societal consequences.’ I’m not so sure that Prince of Players does ‘deal’ with such issues. The ‘fault’ probably lies with Hatcher’s play, but in its suggestion that Kynaston’s ability to perform male roles is dependent on a conversion to heterosexuality, the libretto seems oddly out of kilter with contemporary mores. Initially, Peg ‘acts’ a woman in imitation of Kynaston. When he draws from her a more realistic performance, he finds that he’s ‘a man’ after all. His ‘identity’ as a woman - in the theatre and in the bed of Villiers - is shattered. At the close his whole life seems to have been a ‘work of artfulness’, not ‘art’: his rigorous professional training and his relationship with Villiers are both presented as deception and self-deception. As a psychological ‘journey’ it feels rather reactionary, even regressive.

In an interview in Opera News in March 2016, Floyd explained that Eyre’s film had excited his musical imagination: “… when I saw the film, I thought, ‘Wow-this has the basic ingredient I think a libretto really has to have,’ which is an atmosphere of crisis. The conflict is built in, through the actions of Charles II and how that affects Kynaston, a young man who has had a brilliant career. The only thing I changed was that the film had more humor than I wanted in it.”

That ‘humour’ seems crucial to me. For there is a distinct lack of irony in Floyd’s opera, such as is present - to judge from the published critical reviews - in Hatcher’s Restoration-burlesque and, from my own recollection, in Eyre’s subsequent cinematic adaptation. In that Opera News interview, the composer described the way the relationship between Kynaston and Hughes “inevitably becomes something sexual … at least briefly, but enough that her countering his view of acting, and her denunciation of his way of overplaying the frailty of women, shakes him up and changes him. He discovers his anger in that scene, and that taps into his innate maleness. He realizes that if he’s going to play male roles, he’s going to play them as a very dominant male.” In Eyre’s film, backstage after the curtain calls Kynaston remarks, “I finally got the death scene right.” So, is Floyd suggesting that as a ‘woman’ it is Kynaston’s role to be die, and as a ‘man’, to do the murdering? I don’t think that’s the intent, but it’s hard to evade the insinuation. And, it contradicts Kynaston’s own angry assertion, when the King remarks on his prowess - “You’re not a performer for nothing, sir: you almost persuaded me!”: “That was not a performance, sir: that was my life!”

Hatcher’s title is taken from John Downes’s 1708 Roscius Anglicanus; Or an Historical Review of the Stage from 1660 to 1706 , in which he remarked that Kynaston, ‘he being then very Young, made a Compleat Female Stage Beauty, performing his Parts so well … that it has since been Disputable among the Judicious, whether any Woman that succeeded him so Sensibly touch’d the Audience as he’. What was praised as an art seems to become something artificial and a cause of shame and disgrace, in need of ‘correction’?

That said, gender and performance are at the heart of the art form that we call opera. If in the 21st century we are having conversations about gender and identity, then - from castrati to en travesti, from Cherubino to Cantonese opera, from Baba the Turk to Octavian - opera has relished gender fluidity since the art form was born. Floyd’s Prince of Players is an interesting contribution to the debate.

Opera America calculate that Susannah is one of the ten most frequently produced North American operas since 1991 (alongside an eclectic range of works including Porgy and Bess, My Fair Lady, Menotti’s Amahl and the Night Visitors, Candide, Heggie’s Dead Man Walking and Little Women by Mark Adamo). Yet, performances of Floyd’s operas in the UK are fairly rare, so this recording is particularly welcome, with its pressing, short scenes, engaging idiom, fascinating characters and context. One hopes that it’s not too long - viruses and financial crises permitting - before we get an opportunity to see a live performance on this side of the pond.

Floyd’s pleasure at having Prince of Players recorded in his lifetime is evident in the album notes, where he writes, ‘having this outstanding performance recorded for the world to hear … my 93 year old heart is filled with joy and oh, so much gratitude!’

Claire Seymour

Carlisle Floyd: Prince of Players

Edward Kynaston - Keith Phares, Margaret Hughes - Kate Royal, Thomas Betterton - Alexander Dobson, King Charles II - Chad Shelton, Sir Charles Sedley, Frank Kelley - Villiers, Duke of Buckingham - Vale Rideout, Miss Frayne - Nicole Heinen, Nell Gywnn - Rena Harms, Lady Meresvale - Briana Moynihan, Mistress Revels - Sandra Piques, Eddy Hyde - Nathaniel Hill, Female Emilia - Jessica Schwefel, Male Emilia - Nicholas Huff, Stage hand - John A. Stumpff , Florentine Opera Chorus (Scott S. Stewart, chorusmaster) Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, William Boggs (conductor)