A soundbite summary of Carlo Pepoli’s libretti of Bellini’s 1835

melodramatic historical romance, I puritani, perhaps? No. The

starting point of Arthur Sullivan’s 1892 romantic comedy-cum-historical

drama, Haddon Hall, a CD of which I was delighted to

receive from conductor John Andrews at the start of lockdown: if I couldn’t

enjoy country house opera festivals this summer, then some stately home

opera would be a welcome replacement.

“Ye stately homes of England,

So simple yet so grand;

Long may ye stand and flourish,

Types of our English land.”

So sing the Chorus, from behind closed curtains, at the start of Haddon Hall. Some musical partnerships seem as inextricably bound

together in English culture as fish and chips, and strawberries and cream:

Flanders and Swann, Britten and Pears, Rodgers and Hammerstein … how about

a Gilbert-lite Sullivan, then?

Disagreements between the two halves of the successful librettist-composer

union around the time of The Gondoliers (1889); Sullivan’s desire

to ditch the tested-and-tried and to compose an English ‘grand opera’;

D’Oyly Carte’s financial problems at the newly opened Royal English Opera

House: much contrived to throw Sullivan’s new ventures off-kilter. But, the

composer’s desire for a lavish domestic life and D’Oyly Carte’s

determination to revive a thriving business led the two men back to light

opera and the Savoy Theatre. A new collaborator was required, however.

Enter one Sydney Grundy, a successful playwright willing to turn his hand

to serving Sullivan’s requirements.

Grundy’s Haddon Hall libretto was based upon the real-life

elopement of Dorothy Vernon, daughter of the Royalist Sir George, with the

son of the Protestant Earl of Rutland, in the 1560s. Grundy shifted the

action forward 100 years, to take advantage of the religious conflicts of

the Civil War period, which intensify the familial loyalties and tensions.

So, Dorothy rejects the hand of her cousin, Rupert the Roundhead (her

father hopes the marriage will deflect the legal claim Rupert has made upon

Haddon Hall) in favour of Sir John Manners; she elopes, is pursued,

returns, and - thanks to the restitution of Charles II to the English

throne - is accepted with her new husband into the family fold.

It hardly sounds drama enough to sustain a two-hour opera; and, though the

libretto is divided into three parts according to the theatrical laws of

exposition, conflict and resolution (Act I ‘The Lovers’, Act II ‘The

Elopement’, Act III ‘The Return’), many deemed - following the premiere of Haddon Hall on 24th September 1892 - that, indeed, it

was not. The characters are flat, often inconsistent, and caricatures

abound. The Daily Telegraph critic observed on 26th

September 1892: ‘The great weakness of the libretto is ... the dramatic

insignificance of the main characters who do nothing to make us care for

them.’ The Musical News condemned Grundy for having ‘gone

out of his way to violate the canons of good taste, by the introduction of

needless extraneous characters’. And, the reviewer in Notes

dismissed the historical displacement, judging it made ‘for the sake of

satirising, not the Puritans themselves, but certain modern Sectaries who

have no real relationship with the Puritans, [it] is a double error of

judgement’.

Not all were so negative, though: Haddon Hall did have a run of

200 performances, not far off the totals achieved by Ruddigore andPrincess Ida. And, many reviews were complimentary, Notes favourably comparing the post-elopement aria, ‘Queen of the

Garden’, and duet, ‘Bride of my youth, Wife of my age’, to Gounod’s duet

for Baucis and Philémon! George Bernard Shaw relished the opportunity to

take some snide swipes at Gilbert, attributing (in his column, Music in London, 28th September 1892) the opera’s

success to ‘the critical insight of Mr Grundy’. And, despite his innate

prejudices, Shaw was on a convincing footing in judging that Haddon Hall confirmed that in Sullivan’s handling of ‘the sort of

descriptive ballad which touches on the dramatic his gift is as genuine as

that of Schubert or Loewe’. Haddon Hall, Shaw observed, contained

‘episode after episode’ of such ballads, ‘tenderly handled down to the

minutest detail of their skilful and finished workmanship’.

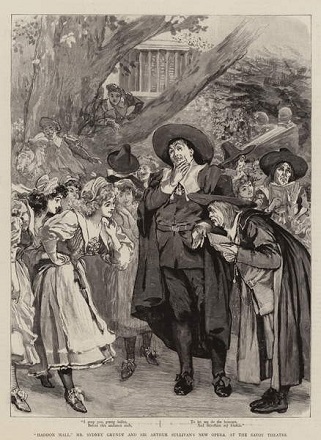

Haddon Hall, Illustration for The Graphic, 1st October 1892 (engraving), English School (19th century), Illustrated Papers Collection/ Bridgeman Images.

Haddon Hall, Illustration for The Graphic, 1st October 1892 (engraving), English School (19th century), Illustrated Papers Collection/ Bridgeman Images.

This recording suggests that Shaw wasn’t wrong: despite the weak dramatic

development and the lack of any real conflict, the ‘ballads’ of Haddon Hall make a loud appeal. Taken out of the theatre, the

opera makes a persuasive case for Sullivan’s music. Characters that are

ill-defined dramatically often have a strong musical identity and set-piece

ensembles may not move the action forward but can form lively vocal

‘tableaux’.

As Dorothy’s companion Dorcas, Angela Simkin gets things brightly underway,

interrupting the BBC Singers’ hearty rendition of the pastoral ensemble

(‘Today it is festival time’) which anticipates Dorothy’s arrival at Haddon

Hall at the start of the opera, with the wry tale of the dormouse and the

snail (‘’Twas a dear little dormouse’) - a figurative account of Dorothy’s

distaste for the metaphorically describes the young woman’s reluctance to

marry her father’s choice, the baying, bragging Rupert. Sarah Tynan is a

self-assured, vibrant Dorothy: if the feisty lass’s smile gleams as

appealingly as Tynan’s soprano in Dorothy’s Act 1 aria, ‘Red of the

rosebud’, then no wonder Manners is smitten. Andrews urges the BBC Concert

Orchestra onwards, the colours swelling and blooming, to convey Dorothy’s

passion-driven decision to defy her father. The idiom may be familiar, but

it’s no less satisfying.

It’s not just the solo songs that beguile, Sullivan enlivens the duets and

ensembles too. The fraught trio ‘Nay, father dear’, in which she forcefully

rejects her father’s wishes, is followed by a lovely duet for Dorothy and

the sympathetic Lady Vernon, ‘Mother, dearest mother’, in which Fiona

Kimm’s mezzo-soprano is a comforting, richly layered complement to Tynan’s

youthful woe. The arrival of her beloved, however, is probably of greater

consolation to the love-struck Dorothy, and Ed Lyon is an ardent John

Manners, his tenor strong, true and lithe - as befits any

knight-in-shining-armour worthy of that name. (Sullivan made some revisions

to Haddon Hall, some of which reduced Manners’ role; this

recording sequences both versions.) Andrews keeps the pulsing strings

hushed in ‘The Earth is Fair’, allowing the woodwind countermelodies and

the cellos’ surges to make their mark. In this aria, as throughout the

opening Act, which essentially serves to introduce the cast of characters,

the tempo flows convincingly, just as the various numbers segue seamlessly.

Sullivan, naturally, doesn’t eschew musical caricature and Grundy provides

him with some ‘classic types’. Before he is disillusioned by the news of

his daughter’s elopement, Sir George sings a paean to England and its

glorious past, ‘In days of yore’, and bass-baritone Henry Waddington

conjures up a terrific image of deluded pomposity - his rolled ‘r’s ring

truly with self-righteousness! - complemented by nationalistic choral

interjections and ironic staccato accompaniment complete with sly flute

commentaries and droll mini-crescendos. The varied forces and details are

brilliantly assembled by Andrews.

Even more absurd is the arrival of Oswald (tenor Adrian Thompson), Manners’

servant disguised as a travelling salesman and fulfilling a mission to

deliver his master’s letter to Dorothy. A blare from the brass whips up the

excited Haddon folk (‘Ribbons to sell’) and Thompson slickly runs through

the sales patter (‘Come simples and gentles’). Even Dulcamara didn’t get

this sort of welcome, the villagers joining in with some vivacious, though

anachronistic, bursts of foreign ‘anthems’ to accompany Oswald’s catalogue

of continental goodies for sale. The bridegroom-to-be makes his appearance

at the end of Act 1, accompanied by an unlikely troupe of Puritan buddies -

Sing-Song Simeon, Nicodemus Knock-Knee, Barnabas Bellows-to-Mend and

Kill-joy Candlemas - though the somewhat formulaic ‘I’ve heard it said’

suggests that Rupert is not so beguiled by the religious cause as he might

be. The villagers are not impressed, and in ‘When I was but a little lad’

baritone Ben McAteer captures Rupert’s over-earnest self-absorption as he

tries to win them over. All are ‘outshone’ in the ludicrous stakes by

McCrankie, Rupert’s fanatical Puritan Scot who hails from ‘the Island of

Rum’. ‘My name is McCrankie’ spouts baritone Donald Maxwell with dour

stringency at the start of Act 2, to the drone of the ‘pipes’ and the hint

of a highland reel.

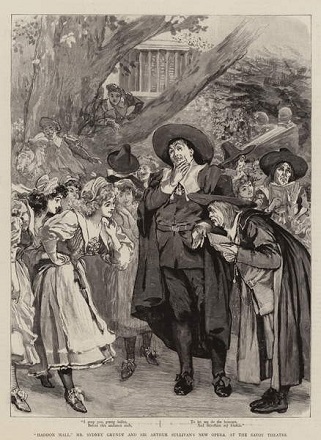

Haddon Hall, Illustration for The Illustrated London News, 1st October 1892, ‘The Flight of Dorothy Vernon’ (engraving), English School (19th Century), Illustrated Papers Collection/Bridgeman Images.

Haddon Hall, Illustration for The Illustrated London News, 1st October 1892, ‘The Flight of Dorothy Vernon’ (engraving), English School (19th Century), Illustrated Papers Collection/Bridgeman Images.

Sullivan’s fluency with pastoral idioms is frequently in evidence, not

least the Act 1 madrigal for chorus and soloists, ‘When the budding bloom

of May’, which Andrews once again keeps swinging buoyantly along as if

fuelled by the villagers’ joyful confidence: ‘All creation seems to say,/

“Earth was made for man’s delight!”’ But, there are some surprises too, not

least the long finale to Act 2 which begins midway through the elopement,

with Dorcas and Oswald lamenting that “The west wind howls”, and closes

with the hoodwinked parents’ discovery of their errant daughter’s

disobedience. The formal and harmonic structures are complex and there’s a

strange juxtaposition of fast-moving development and the stasis with which

it concludes. As Sir George urges the pursuers “To horse - to horse!”, the

Chorus reassure Lady Vernon that the mis-doers will indeed “blunder” and

that nothing with change: “Time, the Avenger,/ Time, the Controller,/ Time,

that unravels the tangle of life,/ Guard thee from danger,/ Prove thy

consoler,/ And make thee again happy mother and wife!” The BBC Singers

(chorus master, Matthew Morley) bloom from unison beginnings to a

wonderfully rich canvas of vocal harmony.

Of course, time will not stand still, but the villagers are not entirely

wrong. Eight years passes - one wonders how that would be conveyed in the

theatre - and Act 3 finds the Vernons being kicked out of Haddon Hall by

the hypocritical Rupert. Sullivan’s invention keeps spinning in this final

Act, with a lovely aria for Kimm as Lady Vernon bids farewell to her

friends, ‘Queen of the Garden’, and a still better duet for the evictees,

‘Bride of my youth’, in which Kimm and Waddington put past conflicts behind

them and look forward optimistically to peace and companionship in their

dotage. In the end, it’s the restoration of the monarchy that

re-establishes familial harmony, leads the villagers to rebel against the

Puritan restrictions which makes their lives so dull, prompts the return of

Dorothy and John, and brings about the reinstatement of Sir George as Lord

of Haddon Hall. “To thine own heart be true!” cry all at the close. It’s

stirring stuff!

It was the convention to begin an evening at the Savoy Theatre with a

‘curtain raiser’, and Christopher O’Brien’s scholarly edition of two such ‘lever de rideau’, Captain Billy and Mr Jericho ( Musica Britannica Volume 99, Stainer & Bell, 2015) has

furnished Andrews, his singers and musicians with some choice examples of

the genre with which to complement Haddon Hall.

The two short works share a librettist, Harry Greenbank. Captain Billy, composed by François Cellier, D’Oyly Carte’s

Musical Director from 1879 to 1913, was a curtain raiser toThe Nautch Girl (a comic opera composed by Edward Solomon) on 23rd September 1891, and relates the tale of the

eponymous former pirate’s return to his family after ten years at sea,

plying his disreputable ‘trade’. There’s a terrific quartet for Captain

Billy’s ‘widow’ (Fiona Kimm), her daughter Polly (Eleanor Denis) with whom

their lodger Christopher Jolly (Ed Lyon) is smitten, and the landlord of

The Blue Dragon Samuel Chunk (Henry Waddington), which culminates in a

graceful, foot-tapping hornpipe led by a vibrant trumpet. The voices blend

thrillingly, but are interrupted by the arrival of Ben McAteer’s Captain

Billy who despite celebrating his arrival with a smug swagger (‘A pirate

bold am I’), is disconcerted to learn from Chunk that the nephew whom he

disinherited 20 years earlier - abandoning him in the desert with clothes

labelled ‘Christopher Jolly’ - is at that very moment examining the parish

registers to uncover the mystery of his birth.

The similarly tuneful Mr Jericho was composed by Cellier’s

assistant at the Savoy and the Royal English Opera House, Ernest Ford, who

had studied with Sullivan at the Royal Academy of Music, and with Lalo in

Paris. The premiere on 18th March 1893 raised the curtain for Haddon Hall, with a tale of the bankrupt aristocrat, Michael de

Vere, and his omnibus-driver son, Horace, both resident in Kensal Green,

and the fulfilment of Horace’s romantic dreams through the manoeuvrings of

one Mr Jericho (celebrated manufacturer of Jericho’s Jams). As the

eponymous businessman, McAteer’s gleeful glorification of his company’s

celebrated condiments is exuberantly colourful, while Eleanor Denis’s

poised Winifred (daughter of Lady Bushey) and Lyon’s good-natured Horace

share a sweet serenade of mutual admiration, supported by warm strings and

touching oboe, as their hearts go “pit-a-pat”. Imitation Sullivan these two

curtain-raisers might be, but they are certainly not second-rate

substitutes.

Sitting comfortably at home, listening to a recording of Sullivan’s Haddon Hall, one does not lament the absence of Gilbertian irony

such as one might do in the opera house. If Haddon Hall is static,

dramatically and symbolically so - freezing historic English

grandeur in operatic aspic perhaps - it is not, thanks to Sullivan’s score,

lacking in sensitivity or interest.

Grundy’s libretto makes clear that “the clock of time has been put forward

a century, and other liberties have been taken with history”, and this ‘out

of time’ quality was noted by the Sunday Times reviewer, on 25 th September 1892: ‘An English story with a fine healthy English

tone, set to music essentially English in idea, form, and character, Haddon Hall … is one of those happy combinations of national

qualities that can never appeal in vain to popular audiences. It breathes

at every point the true racial spirit.’ In similar vein, the Musical News praised Sullivan’s ‘skilful assumption … of the

artforms so greatly perfected by our composers of former days’, for we see

in ‘English music of the best kind certain qualities analogous to the best

traits of our national character - simple earnestness, straightforward

naturalness, and prompt, but unexaggerated expression’.

Such sentiments are either twee, embarrassing, or to be condemned today,

depending on one’s personal view. But, I can’t help feeling that a certain

‘timelessness’ - as well as a little triviality and frivolousness - is not

unwelcome in times when all seems beset by bewildering change and upheaval.

Claire Seymour

Sir Arthur Sullivan: Haddon Hall (1892)

John Manners - Ed Lyon (tenor), Sir George Vernon - Henry Waddington

(bass-baritone), Oswald - Adrian Thompson (tenor), Rupert Vernon - Ben

McAteer (baritone), McCrankie - Donald Maxwell (baritone), Dorothy Vernon -

Sarah Tynan (soprano), Lady Vernon - Fiona Kimm (mezzo-soprano)

Dorcas - Angela Simkin (mezzo-soprano), BBC Concert Orchestra, John Andrews

(conductor), BBC Singers (concert master, Matthew Morley)

Ernest Ford - Mr Jericho (1893)

Michael de Vere - Henry Waddington, Horace Alexander de Vere - Ed Lyon, Mr

Jericho - Ben McAteer, Lady Bushey - Fiona Kimm, Winifred - Eleanor Dennis

(soprano), BBC Concert Orchestra, John Andrews (conductor)

Francois Cellier - Captain Billy (1891)

Captain Billy - Ben McAteer, Christopher Jolly - Ed Lyon, Samuel Chunk -

Henry Waddington, Widow Jackson - Fiona Kimm, Polly - Eleanor Dennis, BBC

Concert Orchestra, John Andrews (conductor)