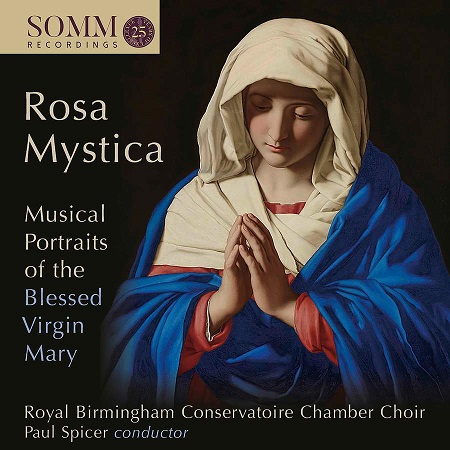

To distinguish this venture, Rosa Mystica: musical portraits of the Blessed Virgin Mary, from

the crowds, in curating and recording the repertory presented Spicer

professes to have aimed to achieve temporal, geographical and musical

diversity: ‘to demonstrate something of the range of styles which have

inspired composers from the 16th to the 21st

centuries’ and to present a ‘truly international offering’. In fact, only

two of the fourteen compositions presented date from before the 20 th century, four are by living composers, and the seventeenth

and eighteenth centuries are entirely neglected. Six works are by composers

who were born outside the UK, though several studied in London or were

immersed in English liturgical traditions. However, if the ‘premise’ is a

little shaky, the quality of the performances certainly is not, and there

is stylistic variety which confirms the personal nature of faith, and the

individual manner of expression of spiritual hope and consolation, within

broadly shared theological parameters.

The earliest Marian setting that Rosa Mystica presents is Ave cujus conceptio by Nicholas Ludford (1485-1557). Ludford, who

served at St Stephen’s chapel of Westminster Palace from c.1520 until the

Royal Chapel was dissolved in 1547, is not one of the best-known of the

Tudor polyphonists, but this large-scale prayer-motet which sets a

five-verse text based on the Corporal Joys of Our Lady - her Conception,

Nativity, Annunciation, Purification and Assumption - suggests that he

should be. From the first stanza, the interplay of high voices is aspiring

and adventurous; then the lower voices take over. There’s a palpable

alertness and vivacity in this recording. The individual lines are muscular

and finely sculpted; collectively, the rich web spins fecundly. The

acoustic is not especially resonant, and this means that we hear vocal

entries and points of imitation, as if set in relief. Yet, there is a

luminosity too: the melismatic threads shine. Spicer sustains the momentum

and the culminating cadences throb with fervent belief.

Spicer and his singers then leap forward more than 300 years to Bruckner’s Ave Maria of 1861. Bruckner wrote three settings of this text: the

first was composed in 1856 when Bruckner was living and working at the St

Florian’s monastery; the final setting was for solo low voice, in 1881. The

seven-voice 1861 setting employs a modal style which reaches back to

Ludford and his fellow Renaissance musicians. Spicer encourages his singers

to emphasise the antiphonal nature of the setting - presumably designed to

exploit the acoustic in Linz Cathedral, where Bruckner was organist from

1855 to 1868. The initial exchanges are quite gentle but the repetitions,

“Jesus”, build to a fervent cry of glowing radiance, and this leads to a

shimmering, soaring soundscape, “Sancta Maria”, which is carefully guided

back down to earth. The concluding “Amen” diminishes confidently, its

collective consolation unwaveringly confirmed.

There’s a very English focus when Spicer turns to the 20th

century. Healey Willan (1880-1968) may have served as precentor at the

Anglo-Catholic parish of St Mary Magdalene in Toronto from 1921-68, but he

was born in England, began his musical training at eight years old at St

Saviour's Choir School in Eastbourne, subsequently worked as organist and

choirmaster at several churches in London, and was for ten years organist

and choirmaster of St John the Baptist Church on Holland Road in London,

before emigrating to Canada in 1913. ‘I beheld her, beautiful as a dove’

(1928) was the first of three motets for the Feast of Our Lady which Willan

composed in 1928-29. It is a two-minute masterpiece, the purity of the

unaccompanied SATB setting being enhanced by the narrow confines of the

vocal lines (the soprano encompasses an octave and does not rise above

e’’). Spicer makes each textual phrase a naturally exhaling breath, the

triplets coursing easily and the cadences coming to comforting rest.

Benjamin Britten gives the disc its title. Rosa Mystica, one of

the seven movements of A.M.D.G. (Ad majorem Dei Gloriam) which set

text by Gerald Manley Hopkins, was one of the first works that Britten

composed having decamped to the US in 1939. Originally intended for

performance by a quartet Peter Pears planned to establish in London, named

the ‘Round Table Singers’ - it remained unperformed during Britten’s

lifetime. A.M.D.G. was finally heard in 1984 and published in

1989. In his

Britten Choral Guide

, Spicer declares: ‘These pieces are seriously demanding and each one

presents new challenges. The choir that can perform the complete score

successfully is confident, ambitious, has a good sense of humour, and has

sopranos and tenors capable of high tessitura work. It helps too if the

conductor is something of an amateur psychologist who can interpret these

sometimes tortured poems in the light of Gerard Manley Hopkins’ Jesuit

affiliation (the title is the motto of the Jesuit order), Britten’s

homosexuality and his deep attachment to his mother.’ Well, if that’s quite

a lot to take on, the RBCCC are more than up to the task: there’s a

dizzying ‘waltz’-feel to the pedal-point ostinato which - meditative and

magical - spins the other voices in parallel thirds, questing and ever more

impassioned.

If Rosa Mystica had to wait over forty years for its first

performance, Sir George Dyson’s Magnificats are some of the most performed

in the choral repertoire. Spicer selects the second of Dyson’s settings,

written just after WW2 for Hereford Cathedral. The balance between Isabella

Abbot Parker’s soprano solo and Callum Alger’s sturdy organ chords is not

ideal, though the full ATB singers fare better against a sparser

accompaniment. Perhaps, though, the solo voice conveys human vulnerability

and the collective voices overcome doubt? Spicer’s forward-moving tempo

communicates purposefulness and the concluding cadence is confirmative and

certain.

The same cannot be said for Herbert Howell’s Magnificat setting of 1967,

for Chichester Cathedral: there’s a fragility and unrooted-ness - the

chromatic shiftings of the opening bars, the asymmetrical phrases which

never seem to find their home base, the grainy vocal colours which refuse

to coalesce into affirmative hues - which reflect the world issues which,

as his letters and diaries attest, troubled Howells at this time: the Cuban

missile crisis, proliferating nuclear weapons, the assassination of J.F.

Kennedy. There is beauty, too, though, as Spicer and his singers confirm,

even if it is of a haunting and troubling kind. And, as the soprano voices

begin to ascend, and pedal points and a stronger bass line appear in the

organ, a confidence accrues; perhaps man can, after all, overcome,

transcend. The surge towards, and the uplift from, the final shining

cadence is indeed stirring. Martin Dalby (1942-2018) was a Scot who studied

composition with Howells at the RCM. Mater Salutaris, was

commissioned by Glasgow High School and first performed 1981. The RBCCC

capture the devotional wholesomeness of this simple but effective carol.

We move from British shores with Hymne à la Vierge

(1954/55) by Pierre Villette (1926-98). Though he was a classmate of Pierre

Boulez at the Conservatoire National Supérieure de Musique, Villette

eschewed the radicalism of French modernism and instead furthered the

musical language of his predecessors, Debussy, Fauré and Poulenc. Spicer

communicates the fervent, even sensual, religiosity of Hymne à la Vierge, flourishing through the repeated ‘alleluias’ of the

chorus, from which Imogen Russell’s second-verse soprano solo (with choral

hum) offers a soothing retreat. The harmonies of the coda are surprisingly

jazz-inflected, an incandescent afterglow. Similarly, after a long and

somewhat heavy-footed organ preamble, Ave Maria (1993) by Swiss

composer Carl Rütti (b. 1949) seems to aspire towards bluesy harmonies and

irregular rhythms: I find the result ponderous, but that’s not the fault of

Spicer and his singers. Norwegian Trond Kverno (b.1945) composed Ave Maris Stella in 1976. It begins with hymn-like homophony,

develops into vigorous polyphony and accelerates through invigorating

soundscapes: to my ears, it soars where Rütti plods and the RBCCC are

fittingly light of foot, creating a breathless intensity before subsiding

into the serenity of the close.

John Tavener’s prayer, Mother of God, here I stand (a short

extract from the seven-hour The Veil of the Temple, 2003)

is a gentle supplication, sung with soft tenderness, the voices blending

warmly and lovingly. Norwegian Ola Gjeilo (b.1978) studied at the RCM in

London’s and in the US at the Juilliard School. Second Eve (2012)

suggests Tavener’s influence in its combination of simple homophony and

rich harmonies which exploit modal resonances. It receives a beautifully

lyrical and vibrantly coloured interpretation here, never ‘wallowing’,

always searching and reaching forwards. The full-voiced concluding sections

are thrillingly urgent and reverberant. In 2011, St Thomas the Apostle

Catholic church in Los Angeles commissioned Judith Bingham (b.1952) to

compose Ave Virgo Sanctissima, which sets text by Prudentius

(b.348AD), sSt Ambroise (c.337-397) and an anonymous writer. The interplay

of the vocal lines is lucidly defined, and the result is a rich palette of

fine textures and a complex but ardent religiosity.

The disc’s final item brings together past and present. Cecilia McDowall

(b.1951) composed Of a rose in 1993. It sets an anonymous 14 th-century text in lilting, springing dance-like phrases, which

the RBCCC sing with an excited hush which blossoms into a dazzling

“Alleluia!” The young singers make this a lovely celebratory, joyous close.

Diversity is united by theme, and by stylistic, personal and spiritual

threads which connect across time and continents. This is a terrific disc

which will bring much pleasure.

Claire Seymour