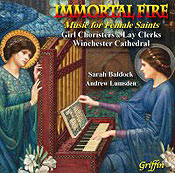

Immortal Fire: Music for Female Saints

The Girl Choristers and Lay Clerks of Winchester Cathedral.

Sarah Baldock, Director; Andrew Lumsden, Organist.

Griffin GCCD 4049 [CD]

The recording “Immortal Fire” presents a varied anthology of music for female saints, excellently sung by the Girl Choristers and Lay Clerks of Winchester Cathedral under the direction of Sarah Baldock. Much of the music is Marian, with additional pieces in honor of St. Cecilia, St. Margaret of Scotland, and St. Ursula. Some of the works are highly familiar — Britten’s youthful “A Hymn to the Virgin,” and his popular setting of Auden’s “A Hymn to St. Cecilia” for instance — and the performances seem familiar, as well. As the pieces are canonical within the cathedral repertory, so too are the interpretations, sung with polish and high accomplishment, but few surprises. However, other works are new or less familiar. For example, Judith Bingham’s “Margaret, Forsaken,” a work commemorating Margaret of Scotland, was commissioned for this recording. The composer’s imaginative use of patterned repetition and ornamental organ effects are evocative of a North Sea moodiness, and the choir responds with an impressive reading that is both intense and dramatic. Herbert Howells — never far from the cathedral choir folder–is represented by two works, a “Hymn for St. Cecilia” and a “Salve Regina.” The former is an expansive hymn tune with a wonderfully uplifting descant to its final verse. The “Salve” is an early work whose chordal gestures are reminiscent of Vaughan Williams, but in the main it is a work showing the developing harmonic fingerprints of Howells’ musical signature, with sweet dissonant propensities and chromatic inflection. Howells graces the concluding acclamations with a memorable treble solo — the embodiment of the text’s “dulcis” — gracefully sung by Tempe Nell.

Much to its credit, “Immortal Fire” has been put together with welcome attention to variety of program. Two large-scale organ works on Marian themes, Flor Peeters’ somewhat predictable “Toccata, Fugue and Hymn on Ave maris stella” and Marcel Dupré’s improvisational “Magnificat” with chant in alternatim, are interspersed among the motets and anthems to good effect, and they are played with flair by Andrew Lumsden. Also intertwined among the vocal polyphony are several monophonic antiphons by Hildegard of Bingen. The choir seems decidedly less at home with these chants than with the other works; the rhapsodic nature of the lines are constrained here into a business-like rush, showing neither the pieces nor the singers to their best advantage.

Where do the singers seem most at home? The performance of Holst’s “Ave Maria,” a stunningly rich eight-voice piece for upper voices, is a remarkable demonstration of this choir at its best. The sound wafts and soars; phrases are finely contoured; the high range is seemingly effortless — all in all, a memorable high point in a recording of many outstanding performances.

It may well be that in the present day we cannot hear this recording without also being aware of its broader context: music celebrating female saints, sung by girl choristers, conducted by one of the few women to gain a musical position in the traditionally all-male bastion of Anglican cathedral music is a combination that brings into focus a dynamic juncture in the history of Anglican cathedral music. Ardent traditionalists have resisted the advance of girl trebles into the cathedral choir stalls, citing among other things the added drain on already tight resources, the feared erosion of the participation of boys, and with that the loss of training of future altos, tenors, and basses, and the demise of a tradition that has been both defining and long cherished. In the past few years, however, more progressive voices have prompted the introduction of girl choristers into the life of a number of English cathedrals — Wells, Salisbury, Coventry, Peterborough, Southwark, and Winchester, among them — and the result, as demonstrated by this present recording,, is very rewarding, indeed.

The Anglican treble sound varies from place to place, be it from girls or from boys, and thus generalizations can be slippery to formulate. However, the emphasis on pure, largely straight-toned singing has long been fundamental, and the introduction of girls has not altered the basic aesthetic assumptions of the tradition. The girls do sing as choristers until an older age, however — seventeen or eighteen years old, long past when boys’ voices would have changed — and thus the girls’ sound may in some instances have a more mature quality. To my ear this takes the form of a sound more lithe; a sound subtly more substantial and textured, as evidenced by the Winchester girl choristers. One wonders, too, if at some subliminal level we don’t listen to boys’ and girls’ voices in a different way, as well. We may perceive in the boy’s treble sound a certain poignance, because it is so obviously ephemeral — we hear it, and — at some level–we know it will not last; someday the boy will be a tenor or a bass. Girls’ voices, too, certainly undergo changes at maturation, but those changes seem more a part of a perceived continuity — high voices remain high voices — and thus we don’t perceive the girl’s voice as emotionally tinged with the same degree of irrecoverability. Thus, the present juncture seems to represent the continuity of a basic aesthetic tradition, yet with subtle changes in the sounds that bring it to life and significant change in those who do the singing. There is much to praise in this evolving of the cathedral tradition: certainly the “social” advances and the enriching of the range of sound are notable. Moreover, as this recent recording from Winchester so amply shows, the present moment is one characterized by a high quality of singing, and this will gratify long after the transient polemics have fallen silent.

Dr. Steven Plank

Oberlin College