So wrote the music critic of the Morning Post following a

performance by the Italian cellist, Carlo Alfredo Piatti, on 12 th July 1844, as part of the third of that year’s three matinÈe

concerts at the Hanover Square Rooms organised by the pianist Theodor

Dˆhler (and recalled by Morton Latham in his 1901 monograph Alfredo Piatti – A Sketch).

Piatti’s Operatic Fantasy on three numbers from Bellini’s penultimate opera

remained unpublished during his lifetime. It is one of three such fantasias

based upon themes by Bellini (La sonnambula and I puritani being the other two operas) that cellist Adrian

Bradbury and pianist Oliver Davies include on the first volume of Piatti’s Operatic Fantasies which was released on the Meridian label last year, and which has now been

followed by this second volume, thereby completing the set of twelve.

Born in Bergamo in 1822, Alfredo Piatti became one of the most renowned

cellists of the 19th century. His father was a violinist but the

5-year-old Piatti began learning the cello, under the tutelage of his

great-uncle, Zanetti, a music teacher and cellist of considerable

accomplishment. By the age of seven he was playing in the local opera

orchestra, and subsequently enrolled at the Milan Conservatoire where he

received lessons from Vincenzo Merighi until September 1837. A successful

performance at the Teatro della Scala in 1838 furnished him with sufficient

funds to undertake a European concert tour, earning acclaim in cities such

as Venice and Vienna.

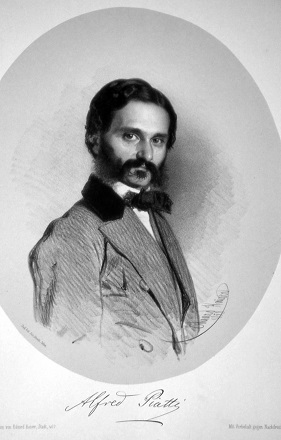

Alfredo Piatti (Lithograph by Eduard Kaiser, 1858)

Alfredo Piatti (Lithograph by Eduard Kaiser, 1858)

1843 found Piatti in Munich. He met Liszt who invited the cellist to share

a concert billing in Paris, gifting him an Amati cello upon learning that

financial pressures had forced Piatti to sell his cello and perform on

borrowed instruments. (Piatti later own the ‘Piatti’ Stradivarius.) He

travelled widely – to Berlin, Breslaw, Dresden, Paris and St Petersburg –

arriving in London in 1844, where the cellist who had spent his boyhood

playing in the opera orchestras of Bergamo, accompanying the finest bel

canto singers of the day, eventually becoming principal cello in Royal

Italian Opera at Covent Garden.

In London he became a distinguished and celebrated artist and teacher. (As

Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielweski explains in The Violoncello and its History, as Professor of Cello at the

Royal Academy of Music, Piatti taught many of the day’s finest cellists,

Hugo Becker, Robert Hausmann, William Edward Whitehouse, William Henry

Squire, Leo Stern and Edward Howell among them.) He became friends with

Mendelssohn, who wrote a concerto for him, as did Arthur Sullivan; he gave

the British premiere of Schumann’s Cello Concerto.

Piatti’s first private performance in London took place at the house of one

Dr Billing, then the medical adviser at the Opera, alongside the Italian

singers soprano Giulia Grisi and tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini. The London

public first enjoyed his playing on 31st May at the Annual Grand

Morning Concert given by Mrs Lucy Anderson, pianist to Queen Victoria, the Morning Post reporting: ‘Signor Piatti, a violoncello performer

from Milan, made a most successful debut. He played a fantasia on themes

from Lucia … His style resembles that of Servais; and a clear

and liquid tone, with great equality all over the board, struck amateurs as

being particularly fine … his certainty and precision were unerring.’

Invited by Dˆhler to play at the first of the Hanover Square Rooms matinÈes

that year, Piatti gave a solo performance that prompted the critic of the Musical World to eulogise, ‘M. Piatti performed a violoncello

fantasia in which he displayed as great a command of this instrument as we

ever recollect to have heard’, and the Athenaeum reviewer to

observe that Piatti had ‘obviously formed his cantabile playing on that of

the singers of his own country’ – an astute comment, given that many

subsequent accounts of his playing noted that his cantabile playing offered

valuable lessons to vocalists.

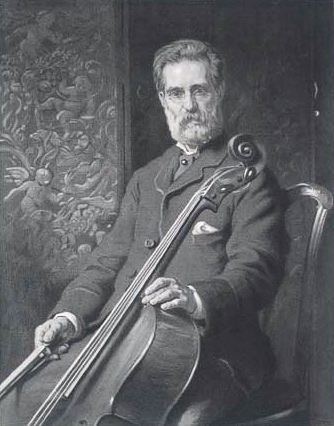

Alfredo Piatti (Frank Holl, 1871)

Alfredo Piatti (Frank Holl, 1871)

A month after his first public London debut, Piatti made his first

appearance at a concert of the Philharmonic Society, on 24th

June, following Mendelssohn’s performance of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano

Concerto with a Cello Fantasia by Friedrich August Kummer. A great

raconteur, later in his life Piatti recalled that this was the only time

that he heard an English audience call out ‘Bravo’ when he was mid-phrase!

The Morning Post praised his ‘magnificent violoncello playing

[which] won universal admiration … the perfection of his tone and his

evident command over all the intricacies of the instrument’, while the Times judged him ‘a masterly player on the violoncello. In tone,

which foreign artists generally want, he is equal to [English cellist

Robert] Lindley in his best days; his execution is rapid, diversified and

certain, and a false note never by any chance is to be heard.’

Piatti was one of the last cellists to play in the ‘old’ style, without an

endpin. A fine composer he enriched his instrument’s repertoire with two

concertos, a concertino, a Fantasia romantica and a SÈrÈnade Italienne. He is best known today for his technically

demanding 12 Caprices Op.25, though he wrote sonatas, songs (some with

cello obbligato), themes and variations and other small works, and produced

important editions of 18th-century cello works by Locatelli,

Boccherini and Bach.

However, it was his fantasy compositions on operatic themes with which

Piatti launched his career and which so dazzled the salons and concert

halls of Europe, and it is these 12 Fantasias, many unknown and unheard

since performed by Piatti himself, that Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies

have ‘exhumed’ from the Piatti archives at the Biblioteca Musicale Gaetano

Donizetti in Bergamo, edited, performed, and now recorded in this

two-volume set.

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies recording ©? Richard Hughes

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies recording ©? Richard Hughes

In conversation, I ask Adrian how this intriguing project had come about.

As a boy he had loved Piatti’s music, he explains – all young cellists know

and play the Caprices! – and when he was asked to perform at the Royal

Academy of Music’s 2011 celebration of their 100-year long residence at

their custom-built premises in Marylebone Road, whose music could be more

apt than that of Piatti, who for 25 years had been the Academy’s Professor

of Cello? Adrian recalls, as a child, hearing his father, clarinettist

Colin Bradbury, preparing for recordings of 19th-century

repertory with the pianist Oliver Davies, and having explored reviews of

Piatti’s playing, he asked Oliver to prepare a score of the unpublished

Fantasia on themes from Bellini’s Beatrice di Tenda, the autograph

manuscript of which was photographed and supplied by Dr Annalisa BarzanÚ,

co-author of Signor Piatti – Cellist, Composer, Avant-gardist

(2001), and musicologist at the Library G. Donizetti in Bergamo. Oliver

studied the cello solo, piano score and orchestral parts, and – taking into

account the evidence that they provided of Piatti’s revisions – was able to

piece together the jigsaw with considerable certainty. Alongside the Beatrice di Tenda Fantasia, at the RAM Adrian and Oliver also

performed the Fantasia on Bellini’s La sonnambula, one of the few

of the 12 that has been published. Enthusiastically received, the Fantasias

“really lived” through their songs, Adrian suggests.

Listening to Adrian and Oliver perform ‘Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda’ (Volume One), I am struck by the way

Piatti fuses lyricism and drama, creating a sense that the melodic material

is evolving organically and inevitably. And, I’m sure the Morning Post critic would

be just as impressed by Adrian’s ability to sing with equal

persuasiveness through the extensive melodic phrases, the energetic

excursions to the cello’s stratosphere and depths, and the delicate

intricacies and ornaments, as he was when he

applauded Piatti’s ‘vanquishing’ of seemingly ‘insuperable’ difficulties –

I certainly heard pitches at a frequency that I don’t think I’ve heard from

a cello before, and beautifully sweet they were too! Moreover, there’s a

lovely spontaneity about Oliver’s and Adrian’s playing which seems to

conjure the excitement of the opera house and live performance. It’s

impossible not smile during the capricious episodes, or to be repeatedly

impressed at how such lighter moods segue with deceptive ease into sweet

sorrow, or troubled turmoil. Oliver’s interjections are perceptive and

sensitive, as if instruments in the pit were being coaxed in their turn to

emerge from supportive accompaniments and join the singer in melody.

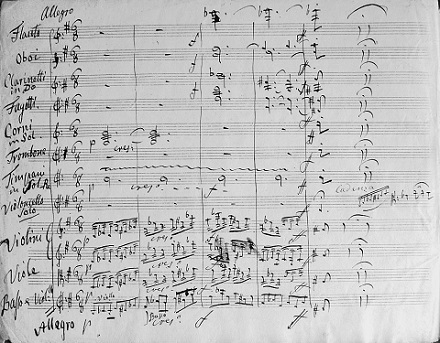

Autograph manuscript of Parafrasi sulk barcarola del Marino Faliero by Alfredo Piatti ©?Annalisa BarzanÚ

Autograph manuscript of Parafrasi sulk barcarola del Marino Faliero by Alfredo Piatti ©?Annalisa BarzanÚ

During the following decade, the duo set about preparing all twelve

Fantasias, and performing them regularly. Every few days, an email to

Annalisa would prompt the swift arrival of the next set of high-resolution

photographs in Adrian’s in-box. When he apologised for ‘bothering’ her so

regularly, Annalisa explained she had written her book primarily so that

Piatti’s music might be heard again. He will “never forget the buzz I felt

the first time that I downloaded the manuscript from my drop-box, printed

it and placed it on the music stand”. Oliver’s experience and knowledge of

the bel canto repertory enabled him to quickly identify the arias upon

which Piatti had drawn and as the prepared Fantasies grew in number, then

Artist By-Fellows at Churchill College, Cambridge, they gave performances

at the College.

Adrian and Oliver present the ‘Introduction et Variations sur un thËme de Lucia di Lammermoor’ which so impressed the Morning Post reporter, in the second volume of Operatic Fantasies. This disc includes three other Fantasias on

operas by Donizetti, who had become a friend of Piatti’s father, Antonio,

whilst they were both studying with Simon Mayr in Bergamo. Piatti, who had

himself played in the Bergamo premiere of the opera in 1838, selected the

climactic closing aria, ‘Tu che a Dio spiegasti’, as his starting point,

preceding his fantasy on Edgardo’s grief-stricken plea that he might join

the dead Lucia in heaven, with an Andante Lento of his own.

The piano’s dark, tense opening resonates with the horrors and histories of

the cemetery in with Edgardo sings his lament, and Adrian captures both the

vulnerability and despair, tapering Piatti’s drooping phrases beautifully,

and the sudden, brief surges of pain and passion during which it seems as

if Edgardo’s heart will burst with anguish. Plunges and peaks, supported by

rumbling, oscillating octaves, sudden transmute from turbulence to

tenderness, as the cello theme voices Edgardo’s transfiguring memories of

Lucia’s purity and virtue. Adrian and Oliver persuasively guide the

listener through the unfolding variations with an effortless lyricism and

technical assurance: the cello’s double-stopped octaves and racing scales

of thirds are pinpoint-true, harmonics ring brightly and whisper softly,

the athletic demands are understated – but no less impressive – and the

melodising unwavering.

Adrian Bradbury ©? Richard Hughes

Adrian Bradbury ©? Richard Hughes

Why had this music languished unheard for so long? Adrian reflects upon the

reluctance of Piatti’s contemporaries to perform his music during his

lifetime: perhaps they were in awe of his virtuosity and wished to avoid

direct comparison? We discuss the subsequent waning of the popularity of

the fantasia form, and of the bel canto style itself. Perhaps the Fantasies

were just too closely associated with Piatti himself? Adrian draws

attention to one Francesco Berger (1834-1933), a

celebrated Professor of Piano at the RAM who invited many Italian refugees

to perform at his home, noting that ‘it was the fashion then for

performances of popular airs – an introduction, air and variation … how

strange now.’

Why were Piatti’s Fantasies so popular, I wonder? “It’s the opera in them,”

suggests Adrian, “one cannot separate bel canto from Piatti”. The Fantasies

“sparkle”, but they are notable not just for their virtuosity: their

musicianship is supreme. “All his life Piatti played this repertory. He

performed with Verdi’s wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, he shared a stage with

the finest singers of his day – Giuditta Pasta, Grisi, Rubini, Luigi

Lablache, Antonio Tamburini, Jenny Lind, Maria Malibran and Michael Balfe.

He wrote from the heart, but the ‘style’ is correct: the Fantasias are a

delight, but Piatti was not simply ‘dabbling’. They are not a vehicle for

virtuosity but, like the Caprices, works of real quality. The virtuosity

was taken for granted, it was the musicianship that Piatti put first.”

Whereas others cobbled together works which would showcase their skill and

dexterity, Piatti took composition seriously and continued studying to the

end of his life.

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies performing in Sala Piatti, Bergamo

Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies performing in Sala Piatti, Bergamo

One can hear just what Adrian means when listening to the only Fantasy in

these two volumes which is not based upon the music of one of Piatti’s bel

canto contemporaries – the ‘Impromptu on an air by Purcell in the Indian Queen’. Piatti wonderfully captures the musical spirit of

the English composer, the precise rhythmic emphases that lend such a

distinctive quality to Purcell’s songs and airs, the smoothly evolving

melodies which Purcell – who might be described as the ‘creator’ of English

secular melody – modelled on the Italian style of expressive singing that

he studied and admired. But, Piatti integrates Italianate delicacies and

graces, the cello interrupting the piano’s simple first phrase with some elaborate flourishes

then tenderly duetting with the theme, first joining as one voice, then

stroking the line with curls, trills, flights. And, just when it seems that

the ground is shifting towards the Italian style, so Piatti shows one to

have been deceived. This is not just an example of Piatti’s compositional

skill but also of his remarkable ability to assimilate varied material.

Adrian’s and Oliver’s performance of Piatti’s stylistic sleights of hand is

utterly magical.

Adrian explains that Piatti’s personal experience is integral to these

works. The bel canto conductor Jeremy Silver advised Adrian that the

Fantasias are fascinating from a conductor’s perspective. “You can see it,

for example, in the articulation that Piatti marked in the Lucia

part: he uses a special articulation mark – a wavy line – a cantabile

indication which he placed over all the operatic phrases. It is to be

played ‘legato, almost separate’. It’s as if Piatti is imagining the

singers on stage beside him.” The decorative fioritura, the declamation of

the recitatives, cadenzas, cadences and ornaments: all are meticulously

indicated. “Piatti inhabits a bel canto ‘skin’ in order to communicate the

essence of the music.” Similarly, the fingering and portamenti are finely

marked. “Even in the Fantasias that were not published [six were published

by Ricordi and Schott]. Though he alone played them, we are sure Piatti was

always aiming for future publication.”

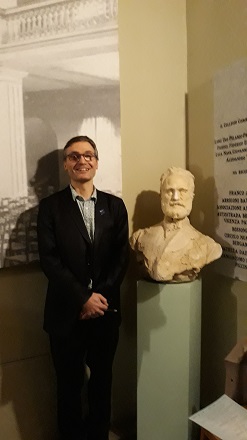

Adrian Bradbury next to bust of Alfredo Piatti, Sala Piatti, Bergamo

Adrian Bradbury next to bust of Alfredo Piatti, Sala Piatti, Bergamo

The bel canto spirit infuses every aspect of these Fantasias, Adrian

believes. He found himself listening to and learning from the singing of

Joan Sutherland, with regard to how to interpret the ornamentation. “The

cello bow becomes the diaphragm; the double-stopping becomes duetting. It must feel as if you are singing; if not, you are in trouble,” he

laughs. When the Royal Opera House presented Bellini’s La sonnambula in 2011, Oliver urged Adrian to see the production.

Admitting that he had not seen the opera before, Adrian tells me of the

tremendous impact that the solo arias, particularly the declamation, had

upon him. Hearing the familiar melodies, it was as if he was experiencing

them entirely anew, learning again and putting the tunes in context.

“String players must listen to singers, and bel canto singers most of all,

to learn to play cantabile.”

Adrian hopes that these recordings will lead to the Fantasias becoming

valuable and wonderful additions to the repertoire. “And we can’t wait to

be allowed to return to Bergamo – so devastated by Covid-19 – to hug the

Piatti scholars once more for sharing their manuscripts and to present more

of the Fantasias in the wonderful Sala Piatti, with the Frank Holl portrait

of Alfredo Piatti looking down at us – approvingly I pray!- from the side

of the concert hall.”

Claire Seymour

Adrian Bradbury (cello), Oliver Davies (piano)

Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies

Volume One: Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda*; Souvenir de La sonnambula, Op.5*; Souvenir des Puritani, Op.9*;

Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe, Op.22; Fantasia sopra alcuni

motivi della Gemma di Vergy; Impromptu on an air by Purcell in the Indian Queen*

Volume Two: Introduction et Variations sur un thËme de Lucia di Lammermoor, Op.2; RondÚ sulla Favorita*;

Souvenir de l’opÈra Linda di Chamounix, Op.13; Parafrasi sulla

Barcarola del Marino Faliero* Rimembranze del Trovatore, Op.21;

Capriccio sur des Airs de Balfe*

*world premiere recording

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Operatic%20Fantasies%20Vol.2%20Meridian.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies” (Volume 2)

product_by=Adrian Bradbury (cello), Oliver Davies (piano)

product_id=Meridian CDE 84659

price=£12.00

product_url=https://www.meridian-records.co.uk/acatalog/CDE84659-Piatti.html#aCDE84659

Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies (Vol.2) – in conversation with Adrian Bradbury

So wrote the music critic of the Morning Post following a

performance by the Italian cellist, Carlo Alfredo Piatti, on 12 th July 1844, as part of the third of that year’s three matinÈe

concerts at the Hanover Square Rooms organised by the pianist Theodor

Dˆhler (and recalled by Morton Latham in his 1901 monograph Alfredo Piatti – A Sketch).

Piatti’s Operatic Fantasy on three numbers from Bellini’s penultimate opera

remained unpublished during his lifetime. It is one of three such fantasias

based upon themes by Bellini (La sonnambula and I puritani being the other two operas) that cellist Adrian

Bradbury and pianist Oliver Davies include on the first volume of Piatti’s Operatic Fantasies which was released on the Meridian label last year, and which has now been

followed by this second volume, thereby completing the set of twelve.

Born in Bergamo in 1822, Alfredo Piatti became one of the most renowned

cellists of the 19th century. His father was a violinist but the

5-year-old Piatti began learning the cello, under the tutelage of his

great-uncle, Zanetti, a music teacher and cellist of considerable

accomplishment. By the age of seven he was playing in the local opera

orchestra, and subsequently enrolled at the Milan Conservatoire where he

received lessons from Vincenzo Merighi until September 1837. A successful

performance at the Teatro della Scala in 1838 furnished him with sufficient

funds to undertake a European concert tour, earning acclaim in cities such

as Venice and Vienna.

1843 found Piatti in Munich. He met Liszt who invited the cellist to share

a concert billing in Paris, gifting him an Amati cello upon learning that

financial pressures had forced Piatti to sell his cello and perform on

borrowed instruments. (Piatti later own the ‘Piatti’ Stradivarius.) He

travelled widely – to Berlin, Breslaw, Dresden, Paris and St Petersburg –

arriving in London in 1844, where the cellist who had spent his boyhood

playing in the opera orchestras of Bergamo, accompanying the finest bel

canto singers of the day, eventually becoming principal cello in Royal

Italian Opera at Covent Garden.

In London he became a distinguished and celebrated artist and teacher. (As

Wilhelm Joseph von Wasielweski explains in The Violoncello and its History, as Professor of Cello at the

Royal Academy of Music, Piatti taught many of the day’s finest cellists,

Hugo Becker, Robert Hausmann, William Edward Whitehouse, William Henry

Squire, Leo Stern and Edward Howell among them.) He became friends with

Mendelssohn, who wrote a concerto for him, as did Arthur Sullivan; he gave

the British premiere of Schumann’s Cello Concerto.

Piatti’s first private performance in London took place at the house of one

Dr Billing, then the medical adviser at the Opera, alongside the Italian

singers soprano Giulia Grisi and tenor Giovanni Battista Rubini. The London

public first enjoyed his playing on 31st May at the Annual Grand

Morning Concert given by Mrs Lucy Anderson, pianist to Queen Victoria, the Morning Post reporting: ‘Signor Piatti, a violoncello performer

from Milan, made a most successful debut. He played a fantasia on themes

from Lucia … His style resembles that of Servais; and a clear

and liquid tone, with great equality all over the board, struck amateurs as

being particularly fine … his certainty and precision were unerring.’

Invited by Dˆhler to play at the first of the Hanover Square Rooms matinÈes

that year, Piatti gave a solo performance that prompted the critic of the Musical World to eulogise, ‘M. Piatti performed a violoncello

fantasia in which he displayed as great a command of this instrument as we

ever recollect to have heard’, and the Athenaeum reviewer to

observe that Piatti had ‘obviously formed his cantabile playing on that of

the singers of his own country’ – an astute comment, given that many

subsequent accounts of his playing noted that his cantabile playing offered

valuable lessons to vocalists.

A month after his first public London debut, Piatti made his first

appearance at a concert of the Philharmonic Society, on 24th

June, following Mendelssohn’s performance of Beethoven’s Fourth Piano

Concerto with a Cello Fantasia by Friedrich August Kummer. A great

raconteur, later in his life Piatti recalled that this was the only time

that he heard an English audience call out ‘Bravo’ when he was mid-phrase!

The Morning Post praised his ‘magnificent violoncello playing

[which] won universal admiration … the perfection of his tone and his

evident command over all the intricacies of the instrument’, while the Times judged him ‘a masterly player on the violoncello. In tone,

which foreign artists generally want, he is equal to [English cellist

Robert] Lindley in his best days; his execution is rapid, diversified and

certain, and a false note never by any chance is to be heard.’

Piatti was one of the last cellists to play in the ‘old’ style, without an

endpin. A fine composer he enriched his instrument’s repertoire with two

concertos, a concertino, a Fantasia romantica and a SÈrÈnade Italienne. He is best known today for his technically

demanding 12 Caprices Op.25, though he wrote sonatas, songs (some with

cello obbligato), themes and variations and other small works, and produced

important editions of 18th-century cello works by Locatelli,

Boccherini and Bach.

However, it was his fantasy compositions on operatic themes with which

Piatti launched his career and which so dazzled the salons and concert

halls of Europe, and it is these 12 Fantasias, many unknown and unheard

since performed by Piatti himself, that Adrian Bradbury and Oliver Davies

have ‘exhumed’ from the Piatti archives at the Biblioteca Musicale Gaetano

Donizetti in Bergamo, edited, performed, and now recorded in this

two-volume set.

In conversation, I ask Adrian how this intriguing project had come about.

As a boy he had loved Piatti’s music, he explains – all young cellists know

and play the Caprices! – and when he was asked to perform at the Royal

Academy of Music’s 2011 celebration of their 100-year long residence at

their custom-built premises in Marylebone Road, whose music could be more

apt than that of Piatti, who for 25 years had been the Academy’s Professor

of Cello? Adrian recalls, as a child, hearing his father, clarinettist

Colin Bradbury, preparing for recordings of 19th-century

repertory with the pianist Oliver Davies, and having explored reviews of

Piatti’s playing, he asked Oliver to prepare a score of the unpublished

Fantasia on themes from Bellini’s Beatrice di Tenda, the autograph

manuscript of which was photographed and supplied by Dr Annalisa BarzanÚ,

co-author of Signor Piatti – Cellist, Composer, Avant-gardist

(2001), and musicologist at the Library G. Donizetti in Bergamo. Oliver

studied the cello solo, piano score and orchestral parts, and – taking into

account the evidence that they provided of Piatti’s revisions – was able to

piece together the jigsaw with considerable certainty. Alongside the Beatrice di Tenda Fantasia, at the RAM Adrian and Oliver also

performed the Fantasia on Bellini’s La sonnambula, one of the few

of the 12 that has been published. Enthusiastically received, the Fantasias

“really lived” through their songs, Adrian suggests.

Listening to Adrian and Oliver perform ‘Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda’ (Volume One), I am struck by the way

Piatti fuses lyricism and drama, creating a sense that the melodic material

is evolving organically and inevitably. And, I’m sure the Morning Post critic would

be just as impressed by Adrian’s ability to sing with equal

persuasiveness through the extensive melodic phrases, the energetic

excursions to the cello’s stratosphere and depths, and the delicate

intricacies and ornaments, as he was when he

applauded Piatti’s ‘vanquishing’ of seemingly ‘insuperable’ difficulties –

I certainly heard pitches at a frequency that I don’t think I’ve heard from

a cello before, and beautifully sweet they were too! Moreover, there’s a

lovely spontaneity about Oliver’s and Adrian’s playing which seems to

conjure the excitement of the opera house and live performance. It’s

impossible not smile during the capricious episodes, or to be repeatedly

impressed at how such lighter moods segue with deceptive ease into sweet

sorrow, or troubled turmoil. Oliver’s interjections are perceptive and

sensitive, as if instruments in the pit were being coaxed in their turn to

emerge from supportive accompaniments and join the singer in melody.

During the following decade, the duo set about preparing all twelve

Fantasias, and performing them regularly. Every few days, an email to

Annalisa would prompt the swift arrival of the next set of high-resolution

photographs in Adrian’s in-box. When he apologised for ‘bothering’ her so

regularly, Annalisa explained she had written her book primarily so that

Piatti’s music might be heard again. He will “never forget the buzz I felt

the first time that I downloaded the manuscript from my drop-box, printed

it and placed it on the music stand”. Oliver’s experience and knowledge of

the bel canto repertory enabled him to quickly identify the arias upon

which Piatti had drawn and as the prepared Fantasies grew in number, then

Artist By-Fellows at Churchill College, Cambridge, they gave performances

at the College.

Adrian and Oliver present the ‘Introduction et Variations sur un thËme de Lucia di Lammermoor’ which so impressed the Morning Post reporter, in the second volume of Operatic Fantasies. This disc includes three other Fantasias on

operas by Donizetti, who had become a friend of Piatti’s father, Antonio,

whilst they were both studying with Simon Mayr in Bergamo. Piatti, who had

himself played in the Bergamo premiere of the opera in 1838, selected the

climactic closing aria, ‘Tu che a Dio spiegasti’, as his starting point,

preceding his fantasy on Edgardo’s grief-stricken plea that he might join

the dead Lucia in heaven, with an Andante Lento of his own.

The piano’s dark, tense opening resonates with the horrors and histories of

the cemetery in with Edgardo sings his lament, and Adrian captures both the

vulnerability and despair, tapering Piatti’s drooping phrases beautifully,

and the sudden, brief surges of pain and passion during which it seems as

if Edgardo’s heart will burst with anguish. Plunges and peaks, supported by

rumbling, oscillating octaves, sudden transmute from turbulence to

tenderness, as the cello theme voices Edgardo’s transfiguring memories of

Lucia’s purity and virtue. Adrian and Oliver persuasively guide the

listener through the unfolding variations with an effortless lyricism and

technical assurance: the cello’s double-stopped octaves and racing scales

of thirds are pinpoint-true, harmonics ring brightly and whisper softly,

the athletic demands are understated – but no less impressive – and the

melodising unwavering.

Why had this music languished unheard for so long? Adrian reflects upon the

reluctance of Piatti’s contemporaries to perform his music during his

lifetime: perhaps they were in awe of his virtuosity and wished to avoid

direct comparison? We discuss the subsequent waning of the popularity of

the fantasia form, and of the bel canto style itself. Perhaps the Fantasies

were just too closely associated with Piatti himself? Adrian draws

attention to one Francesco Berger (1834-1933), a

celebrated Professor of Piano at the RAM who invited many Italian refugees

to perform at his home, noting that ‘it was the fashion then for

performances of popular airs – an introduction, air and variation … how

strange now.’

Why were Piatti’s Fantasies so popular, I wonder? “It’s the opera in them,”

suggests Adrian, “one cannot separate bel canto from Piatti”. The Fantasies

“sparkle”, but they are notable not just for their virtuosity: their

musicianship is supreme. “All his life Piatti played this repertory. He

performed with Verdi’s wife, Giuseppina Strepponi, he shared a stage with

the finest singers of his day – Giuditta Pasta, Grisi, Rubini, Luigi

Lablache, Antonio Tamburini, Jenny Lind, Maria Malibran and Michael Balfe.

He wrote from the heart, but the ‘style’ is correct: the Fantasias are a

delight, but Piatti was not simply ‘dabbling’. They are not a vehicle for

virtuosity but, like the Caprices, works of real quality. The virtuosity

was taken for granted, it was the musicianship that Piatti put first.”

Whereas others cobbled together works which would showcase their skill and

dexterity, Piatti took composition seriously and continued studying to the

end of his life.

One can hear just what Adrian means when listening to the only Fantasy in

these two volumes which is not based upon the music of one of Piatti’s bel

canto contemporaries – the ‘Impromptu on an air by Purcell in the Indian Queen’. Piatti wonderfully captures the musical spirit of

the English composer, the precise rhythmic emphases that lend such a

distinctive quality to Purcell’s songs and airs, the smoothly evolving

melodies which Purcell – who might be described as the ‘creator’ of English

secular melody – modelled on the Italian style of expressive singing that

he studied and admired. But, Piatti integrates Italianate delicacies and

graces, the cello interrupting the piano’s simple first phrase with some elaborate flourishes

then tenderly duetting with the theme, first joining as one voice, then

stroking the line with curls, trills, flights. And, just when it seems that

the ground is shifting towards the Italian style, so Piatti shows one to

have been deceived. This is not just an example of Piatti’s compositional

skill but also of his remarkable ability to assimilate varied material.

Adrian’s and Oliver’s performance of Piatti’s stylistic sleights of hand is

utterly magical.

Adrian explains that Piatti’s personal experience is integral to these

works. The bel canto conductor Jeremy Silver advised Adrian that the

Fantasias are fascinating from a conductor’s perspective. “You can see it,

for example, in the articulation that Piatti marked in the Lucia

part: he uses a special articulation mark – a wavy line – a cantabile

indication which he placed over all the operatic phrases. It is to be

played ‘legato, almost separate’. It’s as if Piatti is imagining the

singers on stage beside him.” The decorative fioritura, the declamation of

the recitatives, cadenzas, cadences and ornaments: all are meticulously

indicated. “Piatti inhabits a bel canto ‘skin’ in order to communicate the

essence of the music.” Similarly, the fingering and portamenti are finely

marked. “Even in the Fantasias that were not published [six were published

by Ricordi and Schott]. Though he alone played them, we are sure Piatti was

always aiming for future publication.”

The bel canto spirit infuses every aspect of these Fantasias, Adrian

believes. He found himself listening to and learning from the singing of

Joan Sutherland, with regard to how to interpret the ornamentation. “The

cello bow becomes the diaphragm; the double-stopping becomes duetting. It must feel as if you are singing; if not, you are in trouble,” he

laughs. When the Royal Opera House presented Bellini’s La sonnambula in 2011, Oliver urged Adrian to see the production.

Admitting that he had not seen the opera before, Adrian tells me of the

tremendous impact that the solo arias, particularly the declamation, had

upon him. Hearing the familiar melodies, it was as if he was experiencing

them entirely anew, learning again and putting the tunes in context.

“String players must listen to singers, and bel canto singers most of all,

to learn to play cantabile.”

Adrian hopes that these recordings will lead to the Fantasias becoming

valuable and wonderful additions to the repertoire. “And we can’t wait to

be allowed to return to Bergamo – so devastated by Covid-19 – to hug the

Piatti scholars once more for sharing their manuscripts and to present more

of the Fantasias in the wonderful Sala Piatti, with the Frank Holl portrait

of Alfredo Piatti looking down at us – approvingly I pray!- from the side

of the concert hall.”

Claire Seymour

Adrian Bradbury (cello), Oliver Davies (piano)

Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies

Volume One: Souvenir de Beatrice di Tenda*; Souvenir de La sonnambula, Op.5*; Souvenir des Puritani, Op.9*;

Capriccio sopra un tema della Niobe, Op.22; Fantasia sopra alcuni

motivi della Gemma di Vergy; Impromptu on an air by Purcell in the Indian Queen*

Volume Two: Introduction et Variations sur un thËme de Lucia di Lammermoor, Op.2; RondÚ sulla Favorita*;

Souvenir de l’opÈra Linda di Chamounix, Op.13; Parafrasi sulla

Barcarola del Marino Faliero* Rimembranze del Trovatore, Op.21;

Capriccio sur des Airs de Balfe*

*world premiere recording

image=http://www.operatoday.com/Operatic%20Fantasies%20Vol.2%20Meridian.jpg

image_description=

product=yes

product_title=Alfredo Piatti: The Operatic Fantasies” (Volume 2)

product_by=Adrian Bradbury (cello), Oliver Davies (piano)

product_id=Meridian CDE 84659

price=£12.00

product_url=https://www.meridian-records.co.uk/acatalog/CDE84659-Piatti.html#aCDE84659