Michael Tippett’s 1943 cantata for tenor and piano, Boyhood’s End, was one of first vocal works composed specifically for Peter Pears and Benjamin Britten. It was first performed on 5th June that year, in London, and sets text adapted from W.H. Hudson’s autobiography, Far Away and Long Ago, in the form of a Purcellian cantata. The subject is the transformation from childhood to adulthood, a theme which would preoccupy Britten himself throughout his career.

In this filmed performance, Boyhood’s End enables English Touring Opera, tenor Thomas Elwin and pianist Ian Tindale to pick up where they left off two weeks ago, as they revisit the musical and thematic world of the first of ETO’s January broadcasts in which they presented Tippett’s slightly later but similarly florid, exuberant and ‘heart-on-sleeve’ song-cycle, The Heart’s Assurance.

I suspect that few today are familiar with the Celtic-descended, Argentine-born Hudson (1841-1922), a Victorian writer and naturalist who, having settled in England in 1874, abandoned an initial attempt to make a London-based career as a literary hack and set about emulating Emerson, Thoreau and the transcendentalists by recreating the spiritual essence of Nature in a serious of essays such as A Nature in Downland (1900) and A Shepherd’s Life (1910). During an illness, when he was in his seventies, Hudson experienced a ‘rare state of mind’ in which he ‘revisited’ his youth: his reminiscence of the wild, vibrant Argentine landscape and the political turbulence inflicted on the country by the dictator, Juan Manuel de Rosas, is presented in the intense prose-poetry of Far Away and Long Ago which juxtaposes the rapture of youth with the disillusionment of adulthood.

Rae Piper and Paul Chantry direct and choreograph. The opaque patches of a misted mirror-screen suggest the distance of the idealised past, and of the former ‘self’, from the disenchanted present. Elwin sings the prosaic text with an impressively sustained vocal virility and clear diction, while the longer melismas are interpreted through gesture. Chantry curls, snatches and clutches: “I only want to keep what I have” sings Elwin, his voice softening poignantly with the elegiac registral fall, indicating an acceptance of the futility of the desire to stop time – what he desires to retain is already lost. Physical movement also offers a visual mimicry of the piano’s youthful energy, unrestrained and edgy; of the desire to “to rise each morning” and revel in the glory of the sun and the sky, from “day to day, and year to year”. The vocal melisma here seems to speed those days and years onwards, as does the linear and motivic independence of piano which drives forwards, unsentimental, inevitable.

Chantry’s spontaneous and free limbs – the flickering legs and wings of insects and birds which mesmerise with their magic and mystery – capture the moment of rapture: “to listen in a trance of delight”. And, Elwin even manages to make the precise ornithological observation engaging as the protagonist recalls the “deep hot nest”: “feel the hot eggs, the five long-pointed cream-coloured eggs with chocolate spots and splashes at the larger end”. Rising to ecstatic heights, Elwin’s tenor is powerful and focused, but also evokes an apt tension; for after the ecstasy comes the recognition of loss. The vocal line is then isolated and contemplative; as if eloquence alone might fulfil a desire, “to lie on a grassy bank with the blue water between me and beds of bulrushes, listening to the mysterious sounds of the wind”. But, the sparse rovings of the disengaged piano lines suggest that hope is feeble. At times, Hudson pours forth a flood of observation – somewhat naïve in its hyper-intense vitality – which is matched by the busy rippling of the piano’s streams: “storks, ibises, grey herons, egrets of dazzling whiteness and rose-coloured spoonbills and flamingos”. But, the energy is false; like the two-dimensional word painting of the horses’ hooves, as echoed visually by the empty whirling of the dancer’s arms and legs.

At the close, there is only a wish, to “gaze and gaze until they are to me living things”. Elwin’s brave head voice is both technically assured and emotionally vulnerable. The protagonist remains between worlds, “floating in the shining void”.

An obvious work with which to follow Tippett’s cycle, the first composed specifically for Pears and Britten, might have been Britten’s own Who are these Children? (1969), the last song-cycle composed by Britten for Pears. But, Shostakovich’s 1973 settings of six poems by Marina Tsvetaeva prove a wise choice, the idiosyncrasy and repetitive intensity of Tsvetaeva’s poetry complementing Hudson’s flamboyance, and a sense of retrospective fatalism – as the aged Shostakovich looks back over a Soviet century and his own life – being shared by both cycles.

Tsvetaeva, born in Moscow in 1892, was one of the 20th century’s finest Russian autobiographical writers, of poetry and prose, memoirs and political diaries. Educated in Switzerland, Germany and France, she began to write poetry after her mother’s death in 1906 and almost immediately began to win praise among Moscow literary circles. The years following the Bolshevik Revolution brought personal and economic suffering, however, and subsequently exile. Her literary success declined, although today it is the memoirs that she wrote in Paris during the 1930s – of her childhood, her friends and of past and fellow poets – which are considered to be her masterpieces. Tsvetaeva returned to Russia in 1939 but was unable to publish her work. Her husband and eldest daughter were arrested for espionage; the former was shot, the latter sent to a labour camp. Tsvetaeva committed suicide, on 31 August 1941.

(mezzo-soprano)

The six poems Shostakovich chose for his song-cycle represent the entire range of Tsvetaeva’s career, from her earliest writings to poems from the 1930s. If there is a uniting thread it might be that many of the poems are dedicated to other poets, and themes of love, art and death recur. This is Shostakovich at his most severe and sparse, but while the opening three songs are particularly reticent, the latter three have moments of rhetorical majesty. Mezzo-soprano Katie Stevenson is able to project their strength of feeling with impressive focus.

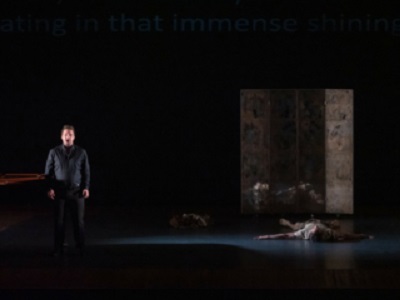

The bare stage and grim greyness of the simple trousers and shirt worn by Stevenson and dancer Bernadette Iglich match the sound-world, the only snatch of colour the red sneakers on their feet, worn too by pianist Ian Tindale who casts aside his polished black shoes. ‘To my verses’, a poet’s lament for their neglected work, is desolate and pained, the piano etching angular lines which seem tense with alienation and rejection, though there are flashes of movement and colour, as when the poet recalls their early writing, “which erupted like splashes from a fountain, like sparks from a rocket”. Stevenson’s Russian diction seems to me to be good; her communication of its sentiments is excellent. Behind her, Iglich kneels and pushes folded plastic sheets across the stage; at the close Stevenson flicks through the folds, then opens one out, an image of her verses which, shrouded now, will like fine wine will be best appreciated in years to come.

Wrapping herself in the transparent sheet, Stevenson sings with soft warmth of the “wily lad, wandering singer, with eyelashes – the longest I’ve ever seen”, in ‘Where does this tenderness come from?” the closing diminuendo conveying the sense of wonder at this unexpected affection and attention. ‘Hamlet’s Dialogue’ presents the Danish prince’s dialogue with his conscience, as he reflects on Ophelia’s corpse, buried in the watery mud. As Iglich and Stevenson curve a sheet between them, the singer’s monotone repetitions ring out with accusatory force, the piano’s stabs and prodding insistence deepening the horror. At the close, Iglich angrily tucks flowers into the folds of the sheet, now a brutal shrine.

The last three songs are more declamatory. Songs four and five set poems from Tsvetaeva’s Verses to Pushkin and Stevenson really opens up her voice at the opening of ‘The poet and the Tsar’, projecting with angry power: “I walked through a gallery of deceased Tsars./ Who is this unbending proud statue?/ So majestic in gold of the regalia./ A pitiful gendarme of Pushkin’s glory.” There’s a Mussorgsy-like majesty about the piano’s proud, grand chords and, holding a sheet aloft Iglich complements this spirit of defiance, though the slapping sound of the sheet whacking the floor in the final bars jars. And, at the end of this song, Shostakovich marks the score with the instruction, attacca – continue straight on. Here there is a pause, as Iglich steps to one side and removes her shoes, which is a pity as the descending parallel octaves that close the song lead directly into the next. But, Tindale’s military staccatos summon a veritable Shostakovichian irony in ‘No, the drum was drumming’. Finest of all is the final song, ‘To Akhmatova’, which breaks the chronological sequence, returning to 1916 and Tsvetaeva’s homage to Anna Akhmatova. Stevenson’s performance combines sombre gravity with a shining vocal energy. Iglich’s kinetic interpretation of poetry’s power and lasting effect is compelling while the listener is held firmly in the passionate grasp of the opening declamatory homage: “Oh muse of lamentation, the finest of all muses!/ O you, fierce fiend of the white night!”

This concert is available to view free of charge on Marquee TV until Friday 22nd January 2021.

Claire Seymour

Tippett: Boyhood’s End

Thomas Elwin (tenor), Rae Piper and Paul Chantry (choreographers), Paul Chantry (dancer), Ian Tindale (piano), Tim van Someren (film director)

Shostakovich: Six Poems of Maria Tsvetaeva Op.143

Katie Stevenson (mezzo-soprano), Ian Tindale (pianist), Bernadette Iglich (dancer), Rahel Vonmoos (director), Tim van Someren (film director)

English Touring Opera, filmed at the Hackney Empire; streamed on Marquee TV, from Friday 15th January 2021

ABOVE: Katie Stevenson in Six Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva