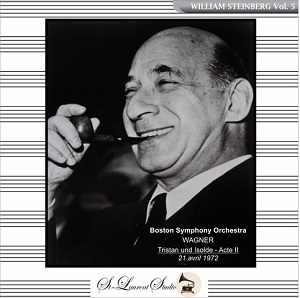

Between 1959 and 1973, a year after William Steinberg ended his tenure as music director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, works by Richard Wagner had featured only rarely on his concert programmes. Just once did he conduct a complete act from a Wagner opera in Boston – Act II of Tristan und Isolde in three concerts during April 1972. Although Steinberg had begun his career at opera houses in Cologne and Frankfurt in the early 1920s, and some of his last performances would be of Parsifal at the Metropolitan Opera in 1974, and there were electrifying performances of Elektra with the New York Philharmonic in 1964, not much else exists on disc.

I think this Boston Tristan und Isolde shows us what we were missing. The Boston Symphony Orchestra were in one sense unfamiliar with this music – this would have been the first time Act II was played complete in a subscription concert – it would have been the first time any part of the opera, beyond the first act Prelude and the third act Liebestod would have been played by the orchestra. Steinberg would be a trailblazer – and afterwards Bernstein and Ozawa would complete Tristan in Boston, each providing the remaining acts between them.

What we do have here is a performance which touches on the inspired, although this has as much to do with Steinberg as it has with the BSO as an instrument in the 1970s. Energized more by its guest conductors, Rafael Kubelik and Colin Davis – and even by the visits of Barbirolli – the BSO could fire on all cylinders when inspired to do so. Under Erich Leinsdorf and the often-ailing Steinberg this orchestra tended to be more febrile; it would clash with the former – though not always – and give highly intense ones with the latter. The ideal match was the spellbinding, electrifying power it had with Colin Davis and the non-American exceptionalism which made Steinberg’s Boston orchestra so very different from other great American orchestras. Their playing was more European, it had a wonderful nobility to it – a Steinberg Bruckner Seventh given in Boston in January 1974 is as exquisite and broad as a Bruckner Fifth he gave with the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra in Munich in 1978. Indeed, it would sometimes be easy to confuse Steinberg’s Boston orchestra with a great visiting European one. When Steinberg conducted elsewhere the results were quite different. There would always be something a little edgy to his New York Phil concerts.

So, to this Tristan concert. Here we have two great American singers, very slightly below their peak. This is perhaps more notably so with Eileen Farrell, if not so much with James King, but there may well be mitigating reasons for this. But even with the voices we have here, the quality is magnificent. They are two singers with very different Wagner legacies and so it’s rather surprising this performance works as well as it does. Farrell would sing some of her earliest Wagner back in 1951 with the New York Philharmonic and Victor de Sabata; King wouldn’t take on his first role – Lohengrin – until 1963 when he was 40. Some of James King’s greatest triumphs would be at Bayreuth; Eileen Farrell would never sing on its hallowed stage – nor on those of Covent Garden or the Met for that matter. Of the major Wagner roles James King would sing there would never be a Tristan, however.

Eileen Farrell would not sing a complete Isolde either but in 1969 at Tanglewood with Leonard Bernstein she sang extracts from the opera with Jess Thomas (Act II Prelude & Love Duet, Act III Tristan’s Death and Liebestod). As in the de Sabata concert from New York, Farrell’s voice for Bernstein is simply huge indicating she hadn’t lost that famed power; by the time of the Boston concert – and one of the criticisms which has been most levelled at this performance – is that Farrell sounds underpowered. A more compelling reason is that Farrell was controlling its size for Symphony Hall and may even have been allowing for her tenor’s smaller tone and unfamiliarity with the role.

King is on record as saying that he never sang Tristan – not because his voice was unsuited to the role – but because of the endurance required: “it’s two Otello’s in one evening”, he said in a 1988 interview with the writer Bruce Duffie. Stamina is clearly not an issue here, and if both Farrell and King give us an Act II which is riveting it’s because stamina falls by the wayside and the focus is elsewhere. King is at least required to give as much here as he would be singing the part of Siegmund during Act I of Die Walküre – a role in which the tenor was notably fine.

The performance opens with a prelude which, unsurprisingly, demonstrates the agility of the Boston Symphony’s wind players. Horns antiphonally echo those of the hunting horns from King Marke’s (superbly sung by Robert Hale) hunting party, their distance simply but ideally captured in the warm acoustic of Symphony Hall. A lesser conductor than Steinberg might not have been able to use his orchestra within this particular hall to create the depth we get in these early scenes between Isolde and Brangaene (Nell Rankin). He centre stages them beautifully, though both Eileen Farrell and Nell Rankin are ideally opposing singers with voices that make this compellingly visible to us. It is not always the case that these roles are quite so well cast.

Visibility is initially everything during the opening scenes of Act II of Tristan und Isolde. It is only as Tristan and Isolde retreat from the visible world – from the darkness of the night into the lightness of daybreak – that the crux of the act takes centre stage and Farrell and King are tested as great Wagner singers. The nucleus of the opera is the Love Duet, ‘O sink’ hernieder, Nacht der Liebe’. Neither soprano nor tenor disappoint here in the slightest: the pledging of desire, its unification into a singular love, are entirely wonderfully done. Often one isn’t surprised by more obvious tenor and soprano couplings – a magnificent Act II with Windgassen and Mödl, conducted by John Barbirolli in 1954, is a very good example – but what makes King and Farrell special is the amplification of their tonal blend, their ability to convey a sensory experience to us which takes this Love Duet beyond the ordinary. Barbirolli, a conductor not especially averse to wearing his heart on his sleeve, for once benefits from such an approach; Steinberg, if not quite taking the BSO in this direction, nor extending the music in quite the same deliberately Romantic style, nevertheless manages to give the scene searing drama. At times he manages to get the Boston players to surge on a massive wave of sound beneath Farrell or King and yet control the orchestra with such dexterity they are never overwhelmed by the orchestra.

Other beautiful moments here are Brangaene’s ‘Watch Song’, which, less chilling than some I have heard, drifts like a mist, and the closing scene between Tristan and Melot (Dean Wilder) which has a swashbuckling intensity raging in Steinberg’s conducting of the orchestra as the two singers ramp up the tension. The closing bars are incisive, like an axe leaving its mark on a bloodstained scaffold.

This is, in many ways, a remarkable Act II, but one which is entirely the sum of all its parts rather than any singular part of it. Perhaps we do regret that there wasn’t a complete Tristan – what, for example, would James King have made of Tristan’s delirium in Act III? There are hardly any weak links here, even in the minor roles. This is James King’s only extensively sung Tristan on disc and is an essential addition to this great Wagnerian tenor’s discography; as is the Isolde of Eileen Farrell. It is one of the few examples of two American singers before the Ozawa era singing Wagner. ysl have managed to obtain a very good broadcast copy of the performance. There is some tape hiss – unavoidable for 1972, though I have heard other Boston recordings from this same year which are less obtrusive, and some which are significantly more so – and it is in stereo. The sound tends to favour the higher spectrum rather than the lower which some listeners may find a little awkward to adjust to. But such is the artistic quality of this concert the sound is more than adequate. It can be purchased as a CD, or as a download on request, and is available only from the seller’s website.

Marc Bridle

Wagner: Tristan und Isolde, Act II

James King/Eileen Farrell/BSO/William Steinberg

Symphony Hall, Boston 21st April 1972

St Laurent Studio YSL William Steinberg Vol.5 Available from: 78experience.com