Auber’s comic operas – once a mainstay of theaters throughout Europe, the Americas, and perhaps beyond – are slowly making their way back into the lives of music lovers through recordings. I have immersed myself with great pleasure in Fra Diavolo, Le Cheval de Bronze, and Manon Lescaut. (The last of these is not to be confused with Massenet’s or Puccini’s Manon operas from decades later; it has its own fascinating tone.)

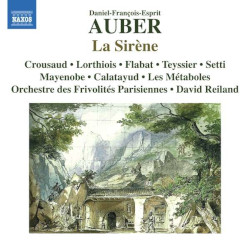

Auber’s La Sirène is a three-act opéra-comique from 1844, much hailed at the time and here receiving what is apparently its first-ever recording (apart from the overture, which has appeared in numerous orchestral collections).

The title role is a singer named Zerlina, who, somewhat like the famous sirens of The Odyssey or like the Rhine River’s Lorelei (but in a mountainous region of Italy), uses her gorgeously supple voice to lure travelers to their doom. More precisely, she draws them to an inn where her brother Scopetto and his fellow bandits rob them. The two other main male characters are attracted to the Siren’s singing, each for his own reason: the young naval ensign Scipion thinks (rightly) that he recognizes her voice as that of his long-lost beloved Zerlina; the impresario Bolbaya hopes he can hire this vocal marvel to sing in the operas that he mounts in the theater of the local duke. The name Bolbaya is a barely disguised reference to Domenico Barbaia (or Barbaja), the renowned impresario of Rossini’s era who ended up bringing the latest trends in Italian opera to Vienna.

In short, La Sirène is in part a “backstage” opera, a bit like Mozart’s Der Schauspieldirektor or Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos. But it is also a “rural Italian bandits” opera, like Auber’s own Fra Diavolo or Offenbach’s Les Brigands, making it a good example of the many French comic operas that were set in a locale that was rural, exotic, or both.

The libretto, by the immensely prolific Eugène Scribe, is witty and full of playful complications. Along the way we meet Scopetto’s fellow bandits and also a police brigade looking to arrest the infamous gang-leader.

At one point the bandits disguise themselves as singers for the upcoming opera in order to gain entry to the palace at Pescara, where they hope to walk off with the duke’s precious treasures. This daffy group-identity switch recalls a major plot turn in Rossini’s Le Comte Ory, in which the gang members disguise themselves as nuns.

Auber’s music is full of tunes that are dance-like, march-like, or, as in the beautiful Act 3 duet for Zerlina and Scipion, sincerely touching. Occasionally Auber finds a way to offset the frequent four-bar phrasing. And the opening wordless song of the Siren ends with a distinctly eerie recollection of the music for the Wolf’s Glen Scene in Weber’s Der Freischütz.

(The quality, variety, and sometime-unpredictability of Auber’s tunes, in his operas generally, helps explain why many of their overtures have remained staples of the orchestral repertoire – and also in arrangements for band. It helps that the overtures themselves are often built out of melodies to be heard in the opera proper.)

The orchestration is skillful. The writing for the voices is expert, as in the opening scenes, in which the offstage, beckoning voice of “the Siren” is heard by several different characters on stage, who all comment on it, in quick succession or sometimes simultaneously.

The recording was made at a 2018 staged performance – with simple paintbox-colored sets and costumes – in the acoustically fine 816-seat Imperial Theater of Compiègne, which was built for Napoleon III. The singers are native French-speakers (Xavier Flabat is from Belgium), and this helps the work come alive. Vocally, they are all capable or better, with Jeanne Crousaud particularly delightful to hear in the coloratura-laden role of Zerlina, “the Siren,” though her voice becomes a bit unsteady as the opera proceeds. Dorothée Lorthiois (in the servant role of Mathéa) has a nicely contrasting, and very firm, mezzo-ish voice, helping us differentiate the two. The two tenors (playing Scopetto and Scipio) likewise contrast helpfully, Jean-Noël Teyssier having a light, sweet sound, Flabat a more substantial one, especially at the upper end.

The orchestra is led with energy and flair by Belgian-born conductor David Reiland. The balance between soloists, chorus, and orchestra is well managed by the engineers, though the microphones are placed quite close, yielding little room resonance (perhaps in order to minimize audience noise). To my delight, all applause has been edited out.

Less happily, many numbers from the score were cut in this production (consistent, the booklet says, with what was done in an 1849 revival in Rouen), and the original spoken dialogue – much of which the production did use – has been almost entirely edited out. The one welcome exception is an intense spoken exchange over orchestral music (i.e., a passage of “melodrama”) at the beginning of the finale, motivating Zerlina to sing a song that will distract the arriving soldiers. Some spoken moments from the stage production can be seen on YouTube, clearly conveying the fun and specificity of the work as performed at Compiègne.

The many omissions allow the work to fit onto a single CD. Predictably, musical numbers arrive one after the other, sometimes creating a bizarre lurch into a new situation or mood that has not been aurally established. Still, you are unlikely to encounter a fuller version of La Sirène, or indeed any other version at all, so now’s your chance.

Naxos provides, online, a scan of a nineteenth-century printing of the complete French libretto (with all the spoken dialogue), enabling the Francophones among us to imagine the full effect of the work. Much of the action, and the humor, occurs in the dialogue scenes. The booklet essay, by opera scholar Robert Ignatius Letellier, is highly informative, and the synopsis helpfully contains track numbers. Still, Naxos should have marked up the French libretto with track numbers to show which arias, etc., are actually on the recording and which have been omitted.

The firm also should have offered – whether printed or online – an English translation of, at the very least, the numbers that are included here. CD manufacturers need to invest in such “added-value” items if they want to attract purchasers. Otherwise we music lovers will become more and more accustomed to subscribing to Spotify or some other streaming service and listening in ignorance.

Ralph P. Locke

D.-F.-E. Auber: La Sirène

Jeanne Crousaud (Zerlina/“Siren”), Dorothée Lorthiois (Mathéa), Xavier Flabat (Scopetto), Jean-Noël Teyssier (Scipion), Benjamin Mayenobe (Bolbaya).

Orchestre des Frivolités Parisiennes, Choeur Les Métaboles, cond. David Reiland

Naxos 8.660436 [CD]

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts , Opera Today , and The Boston Musical Intelligencer . His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The review first appeared, in a somewhat shorter version, in American Record Guide and is posted here by kind permission.