Benjamin Britten’s five Canticles span his compositional career, from 1947 to 1974, and reflect the eclectic musical, poetic and cultural influences and idioms which he integrated into an independent expressive voice. Their texts are disparate, encompassing a Chester miracle play, a 17th-century hymn of union with Christ, Edith Sitwell’s poetic musings on the trauma of the London bombings in 1940, and T.S. Eliot’s elusive allusiveness. Yet, there’s a certain, for wont of a better term, ‘spiritual’ quality that unites them. To the question of whether the Canticles are a religious or secular form, one must surely say, both. Britten, so often an innovator of new genres and forms, here devised a semi-religious vocal form, intended for non-liturgical presentation, embracing purity, passion and profundity. Moreover, spiritual and sensual ecstasy are oft presented via the sparsest means. Britten probably modelled his Canticles on Purcell’s divine hymns; all were written for Peter Peters, alongside a number of their close friends and collaborators.

The tenor voice is, not surprisingly, the uniting participant, and at Leeds Town Hall it was Mark Padmore who introduced each Canticle, in a series of brief but eloquent prefaces. The first Canticle, ‘My Beloved is Mine’, sets a poem by the 17th-century poet, Frances Quarles, which is loosely drawn from the Song of Solomon; it was intended as a tribute to the late Dick Sheppard, former rector of the church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields and founder of the Peace Pledge Union. Padmore suggested that this was a love song from Britten to Pears, and from Pears to Britten. It is, but it is more than that too. There is a spiritual, even mystical, dimension, equal in presence to the sensual, and reflected in the imagery of water and wine, and of grace and purchase: “I’m his by penitence; he mine by grace;/ I’m his by purchase; he is mine, by blood”.

This Love is represented by an image of two streams which join, “two little bank-divided brooks,/ That wash the pebbles with their wanton streams”, and pianist Joseph Middleton captured the ecstatic fusion of fluids – erotic and Eucharistic – in his quasi-mercurial spirallings, like coils from a genie-lamp. Padmore was not as mellifluous as I might have anticipated; there seemed at first a certain tightness and ‘hard-pressed’ quality to his voice. The music is shaped for Pears’ renowned softness and flexibility at the top. But, Padmore more than made up for this with his customary verbal sensitivity. The gentle union of the waters – “in a greater current they conjoin” – was countered by energetic muscularity: “Ev’n so we joyn’d”. The declamatory portrait of “glitt’ring Monarchs that command” swept forward with pride and purpose, Middleton’s piano ever-responsive to the crisp declamation and counterpoint. Padmore’s absolute security was impressive, too: Britten pushes the voice high and low, freely, often detached from any piano-led moorings and the tenor was sure and confident.

The energy spent, piano and voice came together in still waters: “He is my Altar; I, his Holy Place”. Here was consonance and comfort; like an Evangelist, Padmore would lead us to peace.

The second Canticle, ‘Abraham and Isaac’, was composed immediately after Billy Budd; in fact it was the only work Britten completed before his next opera, Gloriana. There are several allusions to the parable in Budd, and one wonders if Britten had Melville in mind when he chose this Chester play for his text, for the American novelist had suggested that, in the fateful closeted interview, Vere ‘may in the end have caught Billy to his heart, even as Abraham may have caught young Isaac on the brink of resolutely offering him up in obedience to the exacting behest’.

This second Canticle was designed for Pears and the mezzo-soprano Kathleen Ferrier, but the latter’s illness saw Britten substitute a boy alto, and it has since become common for the voice of Isaac to be sung by a countertenor, here Iestyn Davies. The two voices, like the afore divided stream, conjoin to speak the words of God, and, supported by Middleton’s heavenly chimes – both deep-rooted and free-turning – Padmore and Davies united in what can only be described as heavenly harmony of sweet dissonance and dynamic consonance, demanding of Abraham to take “That thou lovest the best of all,/ And in sacrifice offer him to me”. A sudden shift of tone and tenor introduced Abraham’s own obedient proclamation, and a quasi-operatic drama unfolded, Padmore’s assertive tenor contrasting with Davies’ lyrical innocence, supported by Middleton’s lightly tripping accompaniment, which – ever more tremulous and tortured – built towards the declaration: “Ah! Isaac, Isaac, I must thee kill!” Padmore violently flung out the words, as if they were rent from his body

Pleading for his father’s blessing, this Isaac sounded so angelic he must surely have already ascended to the spheres. Granting that blessing, Padmore’s tenor rippled with human feeling: “My blessing, dear son, give I thee/ And thy mother’s with heart free.” Middleton expertly aided the fluid progress of the ensuing dramatic narrative: intersecting farewells, so peaceful and tender; then, harmonic darkness, tied to a thunderous bass pedal, the monotonal fixity in the voices suggesting the unbending will of the divine. The intensity tightened and twisted until it exploded in the piano’s thunderbolt. But, as the audience safely know, the threat to mortal innocence will be removed by divine intervention. And, so, the strange harmony of the divine once again shone forth, immanent and immortal. “For ever and ever. Amen,” sang the overlapping voices, with Purcellian simplicity and stature.

The sacrificial slaughter of innocence hovers over the third Canticle, too – a setting of Edith Sitwell’s ‘Still falls the rain’, first performed at Wigmore Hall in 1955 by Pears and Britten with horn-player Dennis Brain. This is essentially a set of six variations for horn interspersed with vocal recitative: the two streams come together in the final organum-like duet, reminding us of the voice of God in the second Canticle: “Still do I love, still shed my innocent light, my Blood, for thee.”

Ben Goldscheider’s quiet mastery in the horn’s dreamy opening statement of the Theme made me long to hear him play Britten’s Serenade for tenor, horn and strings. It’s a cliché to say he made it sound effortless, but he did … and we know it isn’t. The pianissimos were true and sure; the ebbs and flows acutely judged; the tone mysterious but positive; the gentle ‘marking’ of each step in the scalic progress certain and reassuring. “Still falls the rain …,” crooned Padmore at the start of each vocal verse, tender but poignant, with just a hint of man’s pain, before a flood of colour and vigour swept through each vocal declamation. The drama of the fourth verse was gripping, stirring melisma hammering home the horror of Christ’s sacrifice: “Christ that each day, each night, nails there, have mercy on us.” But, the freedom of the following verse similarly confirmed Padmore’s extreme sensitivity to text – text which he absorbs and then shapes and vivifies. Echoes of The Turn of the Screw (written shortly before) spun through the fifth-based spiralling of the fifth horn variation, and Goldscheider punched home rhythms and registral shifts with declamatory confidence. At the close, there was hope within the darkness.

The final two Canticles followed after a long gap, and both set – as Padmore pointed out, rather unusually for Britten – contemporary poetry, that of T.S. Eliot. Commenting on the fourth Canticle, ‘The Journey of the Magi’ – which he noted was written for “the cast of Death in Venice”, James Bowman, Peter Pears and John Shirley-Quirk, but, one might also add, for the cast of Owen Wingrave, the opera that preceded the Canticle – Padmore drew the audience’s attention to Britten’s setting of a particular word, ‘satisfactory’: ‘we continued/ And arrived at evening, not a moment too soon/ Finding the place; it was (you may say) satisfactory.’ This was not intended to suggest adequate or appropriate, suggested Padmore; rather, to convey the Magis’ understanding that through the coming sacrifice, the world would be saved. And, indeed, once again this Canticle – composed, as I say, after Owen Wingrave, the protagonist of which made his own kind of self-sacrifice – takes the idea of sacrifice and expands it to assume a more general significance: ‘were we led all that way for/ Birth or Death?’

Baritone Peter Braithwaite – poised, warm-toned, eloquent – joined Padmore and Davies, and the trio formed both a unified group and individually characterised Magi, the vocal lines alternating vigour and visionary wonder. It’s not possible to overstate Middleton’s contribution to the dramatic and expressive continuity and completeness which unfolded. Arriving at ‘the place’, the Magi did indeed find it ‘satisfactory’, their hushed rising motifs, impelled by the piano’s flourishes and flounces, suggestive of a transfiguring discovery. Wrought intensity interchanged with calm; the piano’s final Purcellian false relations, in the upper register, jangled – wriggling, restless.

The final Canticle, setting Eliot’s ‘The Death of Saint Narcissus’, was composed for Pears and the harpist Osian Ellis, Britten himself being too ill to perform at the piano. Britten reportedly told Rosamunde Strode, ‘I haven’t the remotest idea what it’s about’, but Padmore suggested that the choice of text was less bewildering if one considered it in the light of the preceding opera, Death in Venice. Indeed, I have suggested elsewhere that, just as the earlier Canticles engage with the operas which precede and frame them, so this final Eliot setting – with its images of ‘a dancer before God’, ‘Caught fast in the pink tips of his new beauty’, whose ‘flesh was in love with the burning arrows’ – could be describing Tadzio, retracing the path trodden in Britten’s final opera.

That said, it’s still a strange piece. The harp often threatens to overwhelm the voice, and it’s to Olivia Jageurs’ credit that a taut but conversational balance was sustained here. Jageurs was unfailing responsive to the vocal line and to Britten’s textural and motivic definitions.

St. Narcissus’s ecstatic suffering was both a light and a shadow. And, Padmore proved a similarly protean poet-speaker, moving from the highs to the lows, from the transcendence to the darkness, with persuasive flexibility. The disharmonies between voice and harp, and the vocal line’s constant striving for resolution, created a tension that was sustained to the last. As the harp descended and the vocal line rose – “As he embraced them his white skin surrendered itself to/ the redness of blood, and satisfied him.” – ecstasy dissolved into the ether.

This concert can be viewed on demand until 18th July 2021.

Claire Seymour

Britten: The Five Canticles

Mark Padmore (tenor), Iestyn Davies (countertenor), Peter Brathwaite (baritone), Joseph Middleton (piano), Olivia Jageurs (harp), Ben Goldscheider (horn)

Leeds Town Hall, Leeds; Friday 18th June 2021.

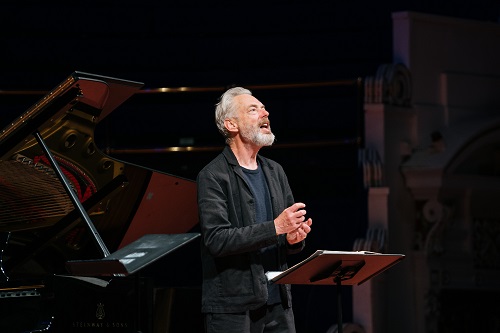

ABOVE: Mark Padmore (tenor) and Olivia Jageurs (harp)