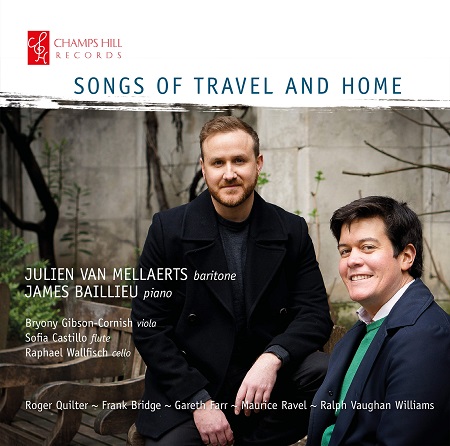

For his debut recital album, Julien Van Mellaerts has compiled a programme of English, French and New Zealand song which, the baritone explains, ‘shows a quasi-autobiographical insight into my life and background’. Titled Songs of Travel and Home, the disc does indeed journey far and wide with respect to geography, language and musical style, reflecting the New Zealand baritone’s dual Antipodean and European heritage, though – excepting a recent commission – the recital has its foot firmly placed in early twentieth-century soil.

I first heard Van Mellaerts sing in 2015 when he took the small role of Reverend Gedge in the Royal College of Music’s Albert Herring, a performance I described as ‘winningly detailed’ and ‘alert to the nuances of the text and aware of his fellow singers’. It was no surprise when two years later he won the Kathleen Ferrier Awards Final, a year in which he also excelled in a French double bill at the RCM, and since then I’ve enjoyed his strong performance as the eponymous Travelling Companion in New Sussex Opera’s 2018 production of Stanford’s ninth and final opera, and his beguiling contribution to a fest of Romantic Liebeslieder at Temple Church in 2019.

We all know what happened to live music shortly after, and Van Mellaerts lost debuts with the Israeli Opera and at the Teatro Nacional de São Carlos in Lisbon, as well as performances at Verbier and with English Touring Opera. He kept busy, curating Whānau: Voices of Aotearoa, far from home which saw New Zealand’s UK-based opera singers, unable to work because of the pandemic, coming together to record a concert of New Zealand, Māori and Pasifika songs which was broadcast from the Royal Albert Hall. But, it’s good to have this Champs Hill album, recorded in November 2020 in the Music Room at Champs Hill in West Sussex, to fill in ‘the gap’, as it were, between those earlier roles and recitals and Van Mellaerts’ 2021 performances at the Verbier Festival, the Mahler Festival in Amsterdam, Wigmore Hall and, as the Count, in Opera Holland Park’s recent Figaro.

In January 2021, Van Mellaerts was invited to join the staff of the Royal College of Music, teaching English Song, and it is with songs by English composers that he and pianist James Baillieu begin and end their recital. Roger Quilter’s ‘Go, lovely rose’ from Five English Love Lyrics Op.24 (1923) opens the disc. The poem, from the Jacobean poet Edmund Waller’s 1645 collection, was part of a cycle of love poems celebrating the charms of Lady Dorothea Sidney or, as Waller called her, ‘Saccharisa’, written shortly before Waller’s exile to France. The lovelorn poet-speaker banishes the rose, ‘that wastes her time and me’, thereby chiding ‘she that’s young,/ And shuns to have her graces spied’, and reminding Saccharisa that her beauty, ‘from the light retired’, shares the brevity of the rose.

Baillieu immediately establishes the graceful flow that ripples idly through the song, and Van Mellaerts’ light baritone is appropriately genteel. Subtle inflections are telling, heightening, for example, the opposition of “shuns” and “abide”, as the rose is order to tell the beloved, “That hadst thou sprung / In deserts where no men abide, / Thou must have uncommended died” – thus intimating the contrasts between rejection and tolerance, between her ephemerality and that which endures. The final stanza opens with the disconcerting command, “Then die”, and Van Mellaerts pushes urgently through this insistent wish for the rose to succumb. Yet, it is not cruelty but pity which prevails at the close. Holding back the tempo just a fraction, Van Mellaerts injects true tenderness into the poet-speaker’s entreaty for the woman who, like the rose, is helpless against Time: “How small a part of time they share / That are so wondrous sweet and fair!” That which is transient is also glorious: the simplicity of the delivery is everything.

‘Now Sleeps the Crimson Petal’ was one of Quilter’s Two Songs Op.3 published in 1904, though it was composed in 1898. In 1915, the composer withdrew the songs, paying the publishers £10 to destroy the plates. Perhaps he was dissatisfied with his own re-arrangement of text from Tennyson’s poem, The Princess, but Baillieu and Van Mellaerts suggest that Quilter was unduly self-critical: the dreamy gentleness of their interpretation is exquisite. Again, though, Van Mellaerts does not fail to see the opportunities in text and melody for meaningful nuance, the closing plea, “and slip/ Into my bosom and be lost in me”, made more precious by the baritone’s holding back of the poetic enjambment, as the change of meter and repetition, “and slip, slip”, and Van Mellaerts’ pianissimo head voice palpably, entrancingly, conjure a drift into ecstatic reverie.

The two songs by Quilter frame Frank Bridge’s Three songs for voice, viola and piano (1906-07) which the composer – a talented viola player and member of the Joachim Quartet – performed, at the piano, in December 1908 at the Broadwood Concert Rooms, with contralto Ivy Sinclair and his sister-in-law Audrey Alston playing the viola part. Van Mellaerts and Baillieu are joined by Bryony Gibson-Cornish, a friend from ‘back home’ who studied alongside the baritone at the RCM.

Gibson-Cornish is a fervent, equal voice in the first song, ‘Far, far from each other’, a setting of Matthew Arnold’s ‘Parting’ – the second of the poet’s ‘Marguerite’ poems. Baillieu’s relentless, impressionistic turbulence conveys the wildness of the metaphorical winds which have forced the beloveds apart, and also the inner anxieties of the Romantic poet who laments not only his irreversible separation from his lover – ‘Far, far from each other our spirits have flown’ (Bridge’s song replaces ‘flown’ with ‘grown’, a far less vulnerable image) – but who also senses the unsurmountable void between his ‘self’ and others, and between his objective and subjective selves: ‘And, what heart knows another?/ Ah! who knows his own?’ Van Mellaerts captures this despairing resignation in the final stanza, where the poet’s entreaties, “Ah, calm me! restore me!”, lack true conviction, and the piano’s final shifting to the major tonality fail to console and reassure.

‘Where is it that our soul doth go?’ sets the final stanza of an untitled poem by Heine. The three musicians share the unrest that the titular question inspires, Baillieu’s sparse lines searching, Van Mellaerts angrily acknowledging man’s mortality, and Gibson-Cornish reflecting more elegiacally on the unanswerable void. The concluding question, “Where is the wind by now did blow?”, is a beautiful but poignant duet for the two ‘voices’, which wind around each other, then diminish, slipping into the piano’s dissolving chromatic fall. Melody is, fittingly, a stronger presence in ‘Music when soft voices die’, and at the close, music lives on in the memory embodied by the piano’s tremulous but vivid vibrations.

Van Mellaerts turns homewards in the next sequence of songs, Gareth Farr’s Ornothological Anecdotes which presents five poems by the NZ poet Bill Manhire, evoking the experiences of the nation’s native birds. The songs were commissioned by Van Mellaerts and Baillieu for their 2019 13-concert tour of New Zealand; four were first performed at Zealandia Wildlife Sanctuary, Wellington on 27th March 2019, while ‘Kiwi’ was added for a subsequent performance at Wigmore Hall in January 2020.

The ‘Dotterel’ darts and flutters, distracting predators from its nest and chicks. Van Mellaerts is an eloquent observer of the bird’s scurrying vulnerability – evoked with fleeting, sparkling touch by Baillieu – and touchingly voices the bird’s anxious ploy: “follow me, follow me.” In contrast, the surprising resilience of the flightless, bright blue takahē is conveyed by the piano’s plodding, circular repetitions and the voice’s low, narrow declamations which culminate in the imperturbable and assertive dismissal, “I’m feeding”. Poem and music echo Victorian parlour song and Gilbert & Sullivan during the kiwi’s confident self-definitions, and Van Mellaerts enjoys both Manhire’s tripping rhyming syllables – “I’m famous in the media/ I’m fast and then I’m speedier/ I’m a kiwiwikipedia” – and the bird’s prosaic surprise at its own success story, expressed in the succinct but excitable closing spoken couplet: “My word my word my word my word/ I’m quite a bird”! The piano’s insistent repeating note and high cocksure flourishes explode in expanding registers and resounding chords in ‘Tūī’, as Mellaerts articulates Manhire’s deliciously irreverent words with clarity and wry glee. Manhire’s poems deserve an essay of their own but I will limit myself to quoting just one of the inebriate tūī’s wonderfully cocky rejoinders: “I love old Benjie Britten and all the stuff he’s written/ I love me all that tasteful masquerade”.

Most moving of all is the song of the now extinct huia, one of New Zealand’s first songbirds, sacred to Māori culture, whose name means ‘where are you?’ and is an onomatopoeic representation of the bird’s distress call. At first the huia’s song is ghostly, distant, but the imagery hints at danger and impermanency, “My wings were made of sunlight/ My tail was made of frost”. Van Mellaerts’ baritone rises and grows more urgent, propelled by the piano’s unrest to throw man’s questioning back at him with angry honesty, “Where are you when you vanish?” The answer bitterly condemns the Victorian colonialists’ ignorance and their monetarising falsification of natural beauty: “I sang upon your coins/ but money courted beauty/ you could not see the joins”. At the close, fragile, plaintive, the bird reminds us of our loss, “I’m made of things that vanish/ a feather on the ground”. The repeated final stanza – as Van Mellaerts’ head voice rises, unprotected – is a bleak self-threnody.

In Ravel’s Chansons madécasses West meets East. At the start of ‘Nahandove’, Van Mellaerts and cellist Rafael Wallfisch stroke the phrases tenderly, perfectly attuned to the wondrous mystery of the nocturnal bird. Baillieu embodies the waking bird’s breathing and rustles which inspire rapturous adulation, “belle Nahandove!”, and quieter affection, “Tu souris, Nahandove”. Van Mellaerts injects the bird’s name with a lovely rhythmic frisson, while flautist Sofia Castillo evokes nature’s aloofness and divinity. The indolence is interrupted by the startling violence of the second Madagascan song: “Aoua! Aoua!” cries Van Mellaerts, high and forceful, warning of white savagery. The narrative of historical savagery unfolds with increasing fury and pain, the piano biting and harsh as alarm and terror propel the litany of ills, which Van Mellaerts articulates with emotive power and clarity. Unaccompanied flute and cello harmonics evoke the scented languidness of the evening heat in ‘Il est doux’. “Le chant plait à mon âme” (Song pleases my soul) exults Van Mellaerts, lazily, luxuriating in the flute’s airy dance above the cello’s serene stillness; but, at the close the cooling breeze and moon’s gleam bring about a sudden, disconcerting retreat from mystery and musing.

The three songs that comprise Ravel’s last completed work, Don Quichotte à Dulcinée (1932-33) were originally commissioned for a film directed by G.W. Pabst starring Fyodor Chaliapin in the title role. Ill health prevented Ravel from fulfilling his contract, and Jacques Ibert stepped in to provide the Russian bass’s songs. Ravel’s three songs persuasively portray aspects of Cervantes’ knight’s character. In ‘Chanson romanesque’ he is Dulcinea’s ardent wooer, and the fluency of Van Mellaerts’ French phrases and tenor-like lightness, together with the piano’s gentle swagger, captures Quichotte’s self-deluding, confident avowals. ‘Chanson à boire’ is boisterously tipsy, self-indulgent and exuberant – Baillieu ‘hiccoughs’ most gracefully! ‘Chanson épique’ is beautifully sung, sweet and earnest, throbbing with sonorous chivalric honour and duty.

The disc concludes with Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Songs of Travel, the ‘Vagabond’ of which steps out with a slightly resentful tread, clipped and curt, as Van Mellaerts conveys a purposefulness and defiance which propels the swift central section. This is strong and immediate characterisation. ‘Let Beauty Awake’ ripples with vitality and receptiveness, and though Baillieu gradually quietens the initial fervour, Van Mellaerts’ baritone retains its warmth: the tuning is impeccable, the phrasing sensitive, the focused tone enriched with a pleasing vibrato and judiciously applied grain. ‘The Roadside Fire’ is surprisingly impetuous and ardent, but it convinces, for the slipping into memory’s embrace in the final stanza is all the more effective because of the earlier directness and realism. In ‘Youth and Love’ the duo capture the tension between the past reminiscence, as suggested by the piano’s static repetitions, and the desire for new experience as intimated by the gentle freedom of the vocal line. This tension explodes with surprising force and resolve, even haste – “He to his nobler fate/ Fares; and but waves a hand as he passes on” – the piano’s later fragmentary recollection of the melody from ‘The Roadside Fire’ offering scant comfort.

The tension of ‘In Dreams’ tugs quietly at the protagonist’s conscience, the piano’s insistent syncopations conveying the speaker’s unease and guilt for having abandoned his beloved. Again, pain bursts forth, wracking both she who weeps and he who reflects on her grief, and Van Mellaerts uses the chromatic rhetoric to communicate the force of such feelings. There is hope, though, in the glistening brightness of the infinite heavens, delicately etched by Baillieu in the following song, and if the stars at first remain unfathomable, then the gift of a shooting star brings a rapid surge of lift and light, and understanding, at the close. Van Mellaerts draws upon the darkness of his lower register, and upon strength and robustness as the melody of ‘Whither must I wander?’ rises, conveying the poet-speaker’s maturity and vision, a maturity which is confirmed in ‘Bright is the ring of words’. This song begins commandingly, then relaxes into the memories that can be relived only through song – as the musical reminiscences of the epilogue, ‘I have trod the upward and the downward slope’, sung here with assurance and peace, confirm.

This is a lovely disc, not just beautifully sung and played, but genuinely personal in tone. The programme is performed with both insight and affection. I know that I shall return to Songs of Travel and Home time and again, most especially for the sensitive interpretation of Bridge’s three songs; for the pathos and humour of Farr’s avian portraits; and for the engaging journey that we make alongside Vaughan Williams’ vagabond.

Songs of Travel and Home is released by Champs Hill Records on 17th September 2021.

Claire Seymour

Songs of Travel and Home: Quilter – ‘Go, Lovely Rose’ (Five English Love Lyrics Op.24 No.3); Bridge – Three Songs for voice, viola and piano H76; Quilter – ‘Now sleeps the Crimson Petal’ (Three Songs Op.3 No.2); Gareth Farr – Ornithological Anecdotes; Ravel – Chansons madécasses, Don Quichotte à Dulcinée; Vaughan Williams – Songs of Travel.

CHRCD 164 [70:00]