Greek heroes are not unaccustomed to squaring up to the whims of gods and fortune, but in bringing Christoph Willibald Gluck’s account of the elopement of Paris, son of King Priam and Queen Hecuba of Troy, and Helen, daughter of Zeus and Queen of Sparta, to the stage, Bampton Classical Opera – while not triggering a Trojan War – have faced more than their fair share of challenges and misfortune this year.

After a sunny opening night at Bampton Deanery Gardens in July, inclement weather nearly scuppered the second performance, which I attended, the rain-sodden stage necessitating frequent mopping, the excision of some of Gluck’s not inconsiderable dance episodes, and disrupting both of the Act finales. So, I was eagerly awaiting the company’s customary September performance at St John’s Smith Square, but that too fell foul of the figurative deities, with members of the cast succumbing to various respiratory ailments. Lucy Cronin was thus obliged to sing – which she did with sparkling clarity – the indisposed Lisa Howarth’s chorus solos in the opening scene, while Milly Forrest – fresh from her award-winning performance at the Royal Overseas League – stepped in at short notice to deliver Pallas Athene’s portentous prophecy in the closing moments. Benjamin Durrant’s chorus part was sung with brightness and vigour by tenor Adam Tunnicliffe, from the wings, with the balance only occasionally unsettled by the chorus’s positioning. Despite these misfortunes, Bampton Classical Opera negotiated the casting challenges with the same unruffled, can-do pragmatism with which they had overcome the summer deluge, bringing their characteristic light-touch irony to Gluck and Calzabigi’s drama of feminine waywardness and a wooer’s wiles.

Premiered on 3rd November 1770 before the Viennese imperial court, Paride ed Elena was the last of Gluck’s three ‘reform’ operas and the first of his operatic ‘Trojan trilogy’. In contrast to Alceste and Orfeo ed Euridice, it was not a great success, and since its premiere performances have been few and far between. Indeed, it seems not to have been performed at all between the 1777 Neapolitan production and the revival in Prague in 1901. It was staged at Drottningholm in 1987. It was Gluck’s last Italian opera; for, in 1770, his patroness, the future Marie Antoinette, married the heir to the French throne, and the composer’s attention turned to Paris and the French stage.

It’s fair to say that this is an opera in which not much ‘happens’. The acts present Paris’s song-fuelled attempts to win Helen’s heart, aided and abetted by ‘Amor’, and there is little genuine theatrical conflict. There are lengthy dance episodes (only slightly truncated here), and rather conventional secco recitatives advance the ‘action’. Gluck’s Preface acknowledges that, ‘The drama of Paris and Helen did not require from the composer’s fancy those strong passions, those majestic images and those tragic situations which shook the audience in Alceste; neither did it necessitate so many grandiose harmonic effects. Thus, the same forceful and energetic music will surely not be expected …’. In the latter profession, though, Gluck sells himself short. He composed a series of beautiful arias and ensembles for the four soprano soloists (at the premiere, the role of Paris was sung by the soprano castrato Giuseppe Millico), and, relishing the well-wrought balancing of simplicity and ornament at St John’s Smith Square, I could not help reflecting that Richard Strauss would surely have loved the delicious vocal richness of the ladies’ trios.

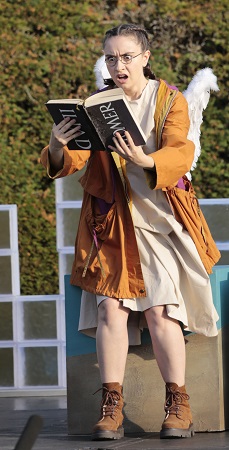

In any case, director Jeremy Gray is not one to let a score’s nuances or a drama’s droll potentialities pass him by. The overture set the tone, the martial opening, subsequent lyrical episodes and closing jubilant dance charting the lovers’ fares and fortunes – as discovered by Lauren Lodge-Campbell’s Cupid when, having used her umbrella-parachute to bring her safely to ground and removed her flying goggles, she browsed through her Homer, uncovering with shock and dismay the prophecy and peripetia which she would then seek to avert. I may be mistaken, but it seemed to me that the musicians of CHROMA, conducted stylishly and crisply by Thomas Blunt, were seated further forward than customary at Bampton productions at SJSS, but, even if I am incorrect, the string playing was particularly immediate and fresh, and the woodwind conversations with the solo voices especially eloquent and clear.

Gray’s simple set presented two screens of irregular rectangles tinted in soft natural tones of brown, grey and teal, reminiscent of the watercolour washes of Ben Nicholson’s Greek-inspired abstracts – as also reflected in costume designer Jess Iliff’s loose tunics and drapes, which matched Classical elegance with relaxed modernism. Nicholson’s belief that such forms give the viewer ‘the actual quality of Greece itself, and this will become a part of the light and space and life in the room’ was brought to fulfilment by the grand Corinthian columns framing the acting space and lighting designer Ian Chandler’s simple but striking hues.

Paris and Helen may end on a portentous note, as the enraged Pallas Athene appears on a cloud to warn the unhappy pair of lovers that her wrath will thwart their future happiness – a prediction of sorrow which they seem only half-heartedly to push aside, for all Gluck’s major-key brightness and the lovers’ avowal that they will not be deterred by destined disaster. But, Gray – and his co-artistic director Gilly French, who supplied a neat and natty English translation of Calzabigi’s libretto – did not let such clouds linger over their production. The dance episodes were nicely tongue-in-cheek, as Oliver Adam-Reynolds and Oscar Fonesca flexed their muscles and flaunted their grace at the command of their Spartan queen – deftly choreographed by Alicia Frost.

High voices prevail, and Gluck scarcely distinguishes them, but Bampton’s cast characterised their roles strongly. Lauren Lodge-Campbell is a natural singer-actor and she relished her busy-bodying, as Cupid-cum-Queen’s counsellor, Erasto. Her soprano is sweet and strong, and Lodge-Campbell – with knowing eyebrows and purposeful frowns – was a playful meddler, consulting her Classics and commanding her acolytes, tiptoeing stealthily and marshalling the actions’ players with a wry wink. Lucy Anderson found a terrific glint and flashes of fire in Helen’s arias, ensuring that we appreciated the Spartan queen’s feisty independence, but she also made sure that we warmed to Paris’s prevaricating beloved.

The role of Paris is a big sing, and Ella Taylor was more than equal to the challenge. What a lovely easeful soprano they have: Taylor’s phrasing was graceful and noble, and there was no strain at all, whatever stamina was required. And, their naturalness and clear diction in the recitatives was exemplary. The blending in the duets and trios was wonderfully comforting, and the combined voices bloomed with colour and spirit. The choral tableaux were neatly despatched. And, finally, I was able to enjoy the deus ex machina – with attendant smoke machine – at the close. Oscillating lights heralded Pallas Athene’s arrival, and Milly Forrest issued her warnings with a biting precision and clarity.

Pallas’s prophecies may be ominous, but Bampton’s courage and conviction are equal to that of any aspiring Greek hero.

Claire Seymour

Paris – Ella Taylor, Helen – Lucy Anderson, Amor (Erasto) – Lauren Lodge-Campbell, Pallas Athene – Milly Forrest, Chorus (Lucy Cronin, Serenna Wagner, Alex Jones, Adam Tuncliffe); Director/Designer – Jeremy Gray, Conductor – Thomas Blunt, Choreographer – Alicia Frost, Costume Designer – Jess Iliff, Lighting Designer – Ian Chandler, CHROMA.

St John’s Smith Square, London; Friday 24th September 2021.

ABOVE: Ella Taylor (Paris), Lucy Anderson (Helen), Lauren Lodge-Campbell (Amor) (c) Jeremy Gray