The Opera di Roma opens its fall season this week with Giuseppe Verdi’s rarely-performed early work, Giovanna d’Arco. The Teatro Costanzi was sold out on Tuesday, for Italians now live peaceably under the world’s most rigorous and effective anti-COVID rules. No one takes public transport, goes to work, or enters a public establishment without wearing a mask, showing a vaccination certificate, and often submitting to a temperature control. The result: the Italian COVID rate per capita is one-sixth that in United States and one-fifteenth that in Britain – and drops further every week. Meanwhile, opera houses are filled.

Giovanna is hardly an obvious choice to launch the season. Verdi wrote it within a month in early 1845 to an undistinguished adaption of Schiller’s play about Joan of Arc. It circulated for a brief time in the 19th century, again during the Verdi revival of the mid-20th century, and now survives on the edge of the repertoire. Critics debate its strong and weak points, but few believe that it matches the most inspired of the composer’s fifteen early operas, such as Macbeth or Nabucco, let alone his first mature opera, Rigoletto, which premiered in 1851. The most one can say is that, amidst some ungainly passages, Giovanna contains some engaging ensembles and at least one modestly memorable aria for each principal.

Yet eminent singers can elevate this music to greatness. We hear this in a legendary 1951 performance from Italian radio where Renata Tebaldi, Carlo Bergonzi and Rolando Panerai – all still in their twenties – interpret the lead roles with astonishing vocal freedom and interpretive imagination. In a recording made two decades later, James Levine leads Montserrat Caballé, Plácido Domingo and Sherrill Milnes in a breathless account that suggests Verdi’s strident Garibaldian nationalism. Over the past decade, Anna Netrebko has used Giovanna as a transition into the Verdi repertoire at the Salzburg Festival (with Domingo switching to baritone) and under Riccardo Chailly at La Scala.

Absent golden age legends, the Rome production brings together about as fine a group of singers as one can engage nowadays. All easily fill the theater with sound and negotiate Verdi’s tricky vocal writing, which includes some exposed a capella passages – even if their ambitions sometimes exceed their vocal resources. Most are born or trained in Italy and characterize strongly.

In the role of Charles VII of France, Francesco Meli is the star of the production. His bel canto tenor fits this role, and he has participated in all the most important European productions of this opera over the past decade. Some might quibble about a lack of vocal warmth, but he easily surmounts the technical difficulties of this high-lying role with an inexhaustible font of steely tenor vocalism interspersed with well-chosen moments of subtle mezzo voce.

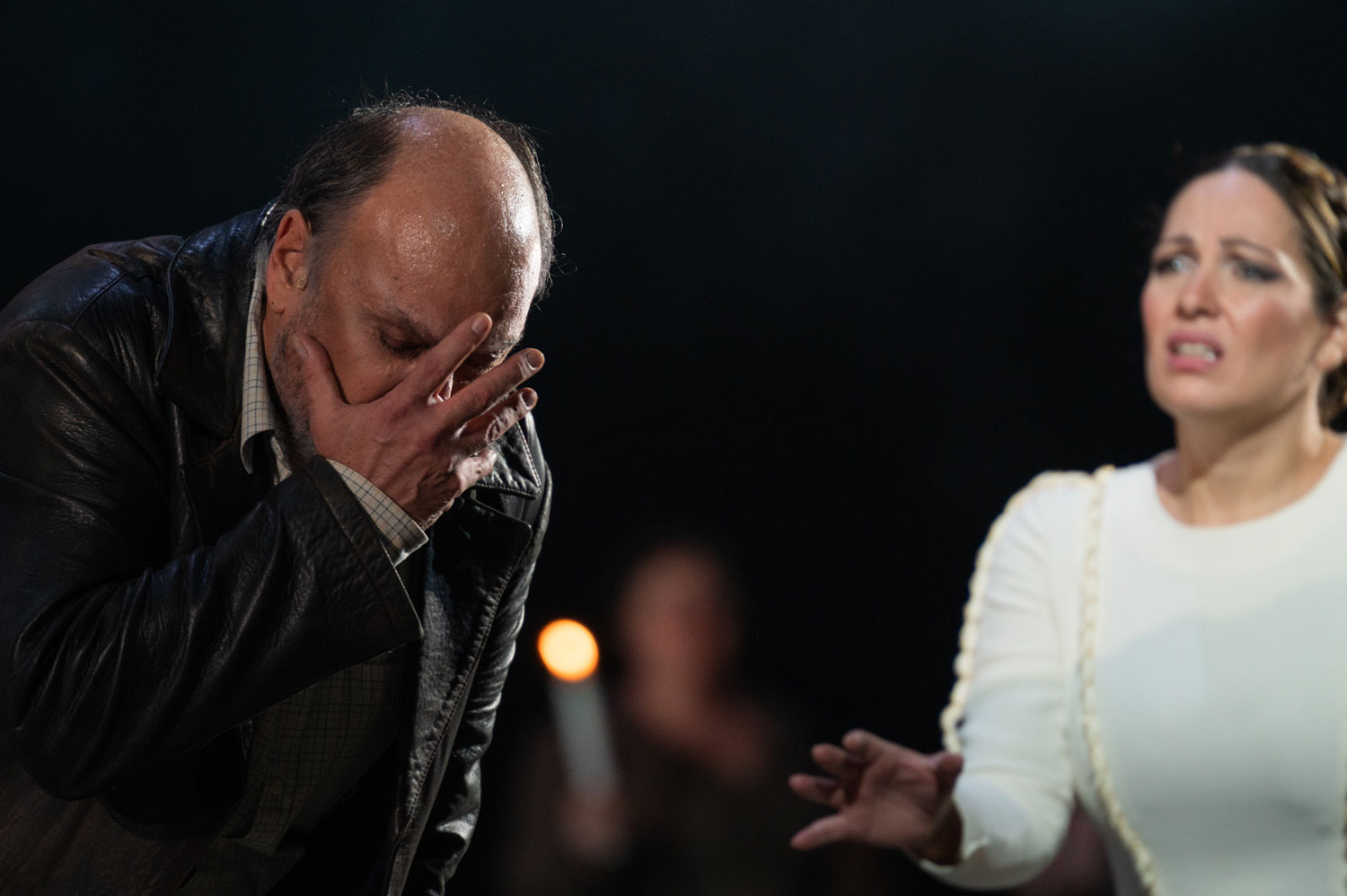

Georgian-born and Italian-trained lyric soprano Nino Machaidze has been moving from bel canto opera toward heavier roles in recent years – but the essence of the voice remains the same. She delivers all the notes, but her vocal timbre never seems relaxed and easy, particularly up high, and her transitions across extremes of volume, wide intervals and successive phases are often choppy. In the role of Giovanna, she sometimes seems to feel her way through music she is performing for the first time. At her best in rare moments of piano singing, she offsets a lack of grace at more dramatic moments with intense vocalism and considerable stage presence.

Veteran baritone Roberto Frontali is experiencing a Indian summer performing major Verdi roles across Europe. His voice has lost some of its former warmth and ease, but has gained an almost tenorial edge at the top – and he has honed his theatrical instincts to make the maximum impression at key moments. Finally, the 46-year old Ukrainian basso profondo Dmitry Belosselskiy, who has been singing in Munich, Vienna and New York, sounds magnificent as the English commander Talbot – I would like to hear more of him in any role.

Daniele Gatti, who began his professional career decades ago with a performance of Giovanna, leads the orchestra with commitment and precision – and the musicians of Rome respond well. Yet the overall effect remains somewhat four-square: even early Verdi can benefit from more idiomatic use of rubato and a wider range of orchestral color. Is he proceeding more carefully to keep soloists and chorus on track?

I save the worst for last. Rome commissioned this new production from the filmmaker Davide Livermore, who is probably the most prominent opera director in Italy today. It is hard to fathom how he has attained this status, for he is pathologically incapable of letting music and drama speak for themselves. Gaudy productions with dozens of fussy visual distractions extraneous to the libretto, powered by creaky stage machinery, are the consistent result.

Before the first note of Giovanna, a ballet dancer with tin-foil wings (right out of a grade-school Christmas show) appears, and seconds later 25 more join in. Throughout the overture they prance around a steeply raked circular stage – movement one can hear as well as see. (Livermore seems to have a thing for angels: in his risible Tosca at La Scala a few years back, he spoiled the delicate sound painting of Rome awakening in the early morning with which Puccini opens Act III by programming the sculptural angel atop Castello Sant’Angelo to flap its metal wings.) In Rome’s Giovanna, the angels clutter up the stage all evening, doubling every action of the singers and the chorus. So, in the last ten minutes, one real and one body double Joan of Arc die (both of them die twice, actually, given the awkward libretto). Then the second (faux) Joan unaccountably comes to life yet a third time to be carried off on the shoulders of her colleagues in the corps de ballet.

Of course, Livermore provides a heady justification for all this – something about a Joan’s pre-Freudian internal tension between spirit and body. Yet such shenanigans only dilute the dramatic focus of what is otherwise a rather intimate opera, drown out or distract from the music, and occasionally generate scenes so preposterous that audience laughs out loud. And don’t get me started on the large circular screen in the middle of the stage on which flowers, butterflies, clouds, water and fire are projected – somewhat reminiscent of a YouTube relaxation video.

Overall, however, this production offers an engaging opportunity to hear a rarely performed early work by Verdi in which the composer is working through musical and dramatic challenges on the way to maturity. Having experienced Giovanna, the creation just six years later of Rigoletto, among the most perfect of all operas, seems even more of an artistic miracle.

Andrew Moravcsik

Giovanna d’Arco

Music by Giuseppe Verdi

Libretto by Temistocle Solera

Giovanna: Nino Machaidze; Carlo VII: Francesco Meli; Giacomo: Roberto Frontali; Talbot: Dmitry Beloselskiy; Delil: Leonardo Trinciarelli. Teatro Dell’opera Di Roma Orchestra, Chorus And Corps De Ballet. Conductor: Daniele Gatti. Director and Choreographer: Davide Livermore.

Above: Nino Machaidze as Giovanna d’Arco.

All photos © Fabrizio Sansoni courtesy of Teatro dell’Opera di Roma